Chapter 1

Introduction: Body Alteration, Artistic Production, and the Social World of Tattooing

A person's physical appearance affects his or her self-definition, identity, and interaction with others (Cooley, 1964 [1902]: 97-104, 175-178, 183; Stone, 1970; Zurcher, 1977: 44-45, 175-178). People use appearance to place each other into categories, which aid in the anticipation and interpretation of behavior, and to make decisions about how best to coordinate social activities.

A person's physical appearance affects his or her self-definition, identity, and interaction with others (Cooley, 1964 [1902]: 97-104, 175-178, 183; Stone, 1970; Zurcher, 1977: 44-45, 175-178). People use appearance to place each other into categories, which aid in the anticipation and interpretation of behavior, and to make decisions about how best to coordinate social activities.

How closely one meets the cultural criteria for beauty is of key social and personal import. The extensive research on attractiveness indicates that there is consensus about the physical factors that characterize beauty. When presented with series of photographs, experimental subjects are able to identify quickly and reliably those that show beautiful people and those that show ugly people (Farina et al, 1977; Walster et al., 1966).

Attractiveness has considerable impact on our social relationships. We think about attractive people more often, define them as being more healthy, express greater appreciation for their work, and find them to be more appealing interactants (Jones et al., 1984: 53-56). Attractive people are more adept at establishing relationships (Brislin and Lewis, 1968), and they enjoy more extensive and pleasant sexual interactions than do those who are not as physically appealing (Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986). Their chances of economic success are greater (Feldman, 1975), and they are consistently defined by others as being of high moral character (Needelman and Weiner, 1977).

Attractiveness, then, affects self-concept and social experience. Attractive people express more feelings of general happiness (Berscheid et al., 1973), have higher levels of self-esteem, and are less likely than the relatively unattractive to expect that they will suffer from mental illness in the future (Napoleon et al., 1980).

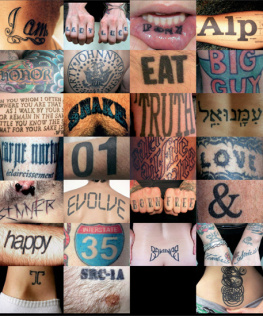

Deviation from and conformity to the societal norms surrounding attractiveness are, therefore, at the core of discussions of appearance and alterations of the physical self. Those who choose to modify their bodies in ways that violate appearance normsor who reject culturally prescribed alterationsrisk being defined as socially or morally inferior. Choosing to be a physical deviant symbolically demonstrates one's disregard for the prevailing norms. Public display of symbolic physical deviance, then, effectively communicates a wealth of information that shapes the social situation in which interaction takes place (Goffman, 1963b; Lofland, 1973: 79-80).

These issues of voluntary body alteration, deviation from appearance norms, and the social impact of purposive public stigmatization provide the central theme orienting this introductory material and the subsequent chapters on the social and occupational world of tattooing. In non-western tribal cultures, the dominant pattern is that certain modes of body alteration typically are deemed essential if one is to assume effectively the appropriate social role and enjoy comfortable social interactions. Failure to alter the physical self in culturally appropriate waysfor example, by wearing a particular costume, or by not having the body shaped or marked in a prescribed mannerlabels one as deviant and, in turn, generates negative social reaction.

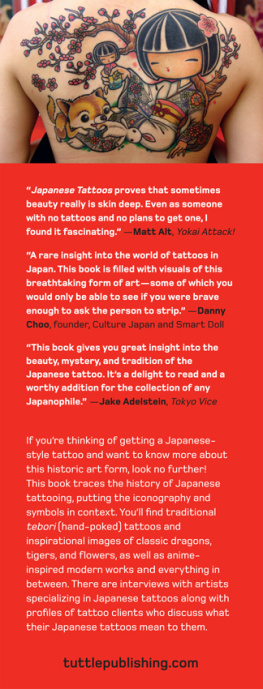

While the pattern shows considerable historical variability, in western societies purposive body alteration has been, and continues to be, primarily a mechanism for demonstrating one's disaffection from the mainstream. Tattooing, body piercing and, to a lesser degree, body sculpting are employed to proclaim publicly one's special attachment to deviant groups, certain activities, self-concepts, or primary associates.

This connection to unconventionality is the key to understanding the organization of and change within the social world surrounding contemporary tattooing in the United States. Like all deviant activities, tattooing is the focus of social conflict. The production world that revolves around commercial tattooing is shaped primarily by its historical connection to disvalued social groups and disreputable practices. On the other hand, this connection to deviance imbues the tattoo mark with significant powerit is an effective social mechanism for separating us from them. At the same time, not all participants in this world have an interest in fostering the deviant reputation of tattooing. As we will see later in this chapter, those who define tattooing as an artistic practice are deeply involved in a process of collective legitimation. Like some photographers (Christopherson, 1974a, 1974b; Schwartz, 1986), potters (Sinha, 1979), recording engineers (Kealy, 1979), stained glass workers (Basirico, 1986), and others (for instance. Neapolitan. 1986), a growing number of tattoo producers are attempting to have their product accepted as art and the related activities of tattoo creation, collection, and appreciation defined as socially valuable. Unlike the craftworkers who have navigated this route to social acceptance before them, however, tattooists labor under a special handicap. Not only must tattoo artists broach the wall separating craft from art, they must also overcome widespread public distaste before they can achieve the certification so grudgingly bestowed by key agents of the mainstream art world. This is what makes the story that follows unique, exciting, and sociologically instructive.

In the remainder of this chapter I present a basic historical and cross-cultural account of body alteration. This is followed by a brief description of the production of culture perspective and the institutional theory of art. These orientations structure my view of the social process by which certain objects and activities are produced and come to be socially valued as legitimate art. Finally, I outline the general organization of the tattoo world with particular emphasis on the burgeoning social movement directed at changing the tarnished reputation of tattooing.

ALTERATIONS OF THE BODY AND PHYSICAL APPEARANCE

Clothing and Fashion

People construct their appearance in a wide variety of ways to control their social identities, self-definitions, and Interactional prospects. At the simplest level, clothing and fashions are adopted in order to display symbolically gender, social status, role, lifestyle, values, personal interests, and other identity features (see, for example, Blumer, 1969; Bell, 1976; Lurie, 1983; Flugel, 1969). In modern societies powerful commercial interests focus significant resources in an effort to shape the meaning of clothing and market fashions to consumers.

Clothing style is of sufficient symbolic importance that it often is controlled through sumptuary laws that allow only members of specific (usually high status) groups to wear certain materials or fashions. In ancient Egypt, for example, only members of the upper class were allowed to wear sandals. Similarly, in eighteenth century Japan the lower-class citizens were forbidden to wear silks, brocades, and other forms of fine cloth.

Unconventional or alienated subcultures commonly use clothing as a mechanism of conspicuous outrage (Bell, 1976: 44-56). The flamboyant costumes adopted by hippies in the 1960s, the punk rocker's torn clothing held together by haphazardly placed safety pins (Anscombe, 1978; Hennessy, 1978), and the outlaw biker's leather jacket (Farren, 1985) and dirt encrusted colors (Watson, 1984) clearly symbolize disaffection with mainstream values and identification with those who are overtly discontented with the status quo. Fashion, like all other mechanisms of appearance alteration, is used symbolically to proclaim group membership and to signal voluntary exclusion from disvalued social categories.

Next page

A person's physical appearance affects his or her self-definition, identity, and interaction with others (Cooley, 1964 [1902]: 97-104, 175-178, 183; Stone, 1970; Zurcher, 1977: 44-45, 175-178). People use appearance to place each other into categories, which aid in the anticipation and interpretation of behavior, and to make decisions about how best to coordinate social activities.

A person's physical appearance affects his or her self-definition, identity, and interaction with others (Cooley, 1964 [1902]: 97-104, 175-178, 183; Stone, 1970; Zurcher, 1977: 44-45, 175-178). People use appearance to place each other into categories, which aid in the anticipation and interpretation of behavior, and to make decisions about how best to coordinate social activities.