Wonders of the Sea and their Media

The sea conceals arcana in its depths which no glance can penetrate, which no genius can depict except with the help of imagination. In the arial and terrestrial worlds, and even in the celestial space, Nature liberally unrolls before our eyes her marvellous pictures. From one pole to the other we may explore all the parts of our domain; but of this ocean, this thin stratum of water a few thousand yards in thickness, stretched over our little planet, we know by sight only the surface and the borders.

How many has the enormous Sphinx devoured of those who have attempted to divine its enigmas, to pierce its mysteries! What matters it? The work goes and goes forward. The human eye has penetrated that formidable night.

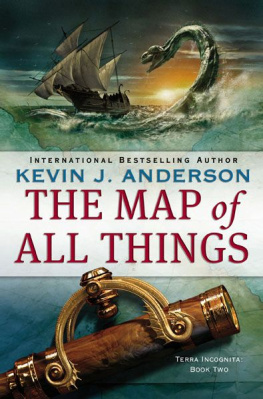

Secret, enigma and night the ocean, its mysteries and wonders: the French natural scientist Arthur Mangin (182487) describes a mood that pervades the nineteenth century as a whole in his extraordinarily successful work, Les Mystres de lOcan (1864). The seas riches had been discovered; now, extravagant efforts were undertaken to achieve dominion over its inhabitants and terrains. In the early phase of the modern age, a panoply of passions whether scientific or artistic, reserved for initiates or the seemingly mad emerged and enriched the popular dramaturgy of riddling and cryptic phenomena with a demimonde of the hitherto unknown. To be sure, talk of wondrous and strange secrets occurred everywhere in works of amateur and popular science, to say nothing of scientific literature that prized the aesthetic dimensions of nature. But the sea, with its unfathomable depths and extraordinary recesses, represented a particularly significant focal point for both epistemology and media aesthetics. From the standpoint of popular science, accounts of wondrous marine phenomena had the peculiarity of being based upon another prodigy not less astonishing than the former. We live in an age of miracles, Jules Michelet (17981874) wrote,

Epistemologically speaking, the realm of the sea lay beyond human reach and was accessible only through considerable technological effort this universe must be experienced by way of artifacts in artificial worlds. In their influential book on oceanographic research, The Machine in Neptunes Garden , Helen Rozwadowski and David van Keuren write:

[T]he oceans are a forbidding and alien environment inaccessible to direct human observation. They force scientist-observers to carry their natural environment with them [O]ceanographys necessary dependence upon technology create[s] a persuasive argument that the machine is the garden. That is, what oceanographers have learned about the ocean has been based almost exclusively on what various technologies, or machines, have taught them.

Marine worlds have to be experienced in mediated form, then. The relation between mankind and the sea is fundamentally based on technology that transforms it so that it may be grasped by human senses and understanding. For some time now, historians of science have focused their attention on the emergence and constitution of new objects of investigation. For all that, it is only recently that insights from the cultural history of media have also been incorporated for example, the fact that generating scientific objects follows from processes of medialization, that is, from various transformations that occur by artificial means. Hereby, a three-dimensional object yields a two-dimensional view, a colourful continuum turns into photographic image marked by contrast and so on. And since, as is well known, media das zu Vermittelnde immer unter Bedingungen stellen, die sie selbst schaffen und sind Put still differently: for a history of the wonders of the sea or, alternately, their exploration, unveiling or decipherment it is essential to consider the constellations of media that enable a given sphere to be known: what aesthetic practices, technologies and instruments were employed, by whom and in what cultural-historical context.

It may seem anachronistic to call the sea a treasure house of modern wonders. Dont monsters, sea serpents and leviathans number among the fears of unenlightened times? Wasnt it precisely the nineteenth century that, with its great passion for amateur science, diffused knowledge about marine life forms, fostered the systematic study of the ocean and witnessed the founding of the field of oceanography? Dont we now know that sea serpents do not exist? The possibilities are not mutually exclusive; all the same, the connections prove complex and intertwined.