The International Behavioural and Social Sciences Library

SOCIAL THEORY AND ECONOMIC CHANGE

TAVISTOCK

The International Behavioural and Social Sciences Library

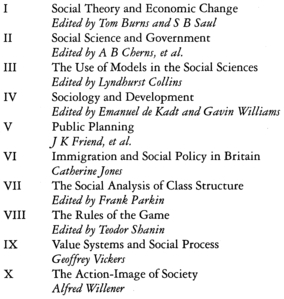

SOCIOLOGY & SOCIAL POLICY

In 10 Volumes

Social Theory and Economic Change

Edited by Tom Burns and S B Saul

First published in 1967 by

Tavistock Publications Limited

Reprinted in 2001 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

1967 The University of Edinburgh

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

The publishers have made every effort to contact authors/copyright holders of the works reprinted in the International Behavioural and Social Sciences Library. This has not been possible in every case, however, and we would welcome correspondence from those individuals/companies we have been unable to trace.

These reprints are taken from original copies of each book. In many cases the condition of these originals is not perfect. The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of these reprints, but wishes to point out that certain characteristics of the original copies will, of necessity, be apparent in reprints thereof.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

Social Theory and Economic Change

ISBN 0-415-26495-2

Sociology & Social Policy: 10 Volumes

ISBN 0-415-26517-7

The International Behavioural and Social Sciences Library 112 Volumes

ISBN 0-415-25670-4

Printed and bound by CPI Antony Rowe, Eastbourne

Social Theory and Economic Change

MICHAEL ARGYLE REINHARD BENDIX

M.W.FLINN EVERETT E.HAGEN

Edited by Tom Burns and S. B. Saul

TAVISTOCK PUBLICATIONS

LONDON NEW YORK SYDNEY TORONTO WELLINGTON

First published in 1967

by Tavistock Publications Limited

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

in II pt Monotype Imprint, one point leaded

by Cox & Wyman Ltd

London, Reading, and Fakenham

The University of Edinburgh, 1967

Distribution in the United States of America

by Barnes & Noble , Inc.

Contributions to the Seminar on the Theory of Economic Change held at the University of Edinburgh in March 1965

University of Edinburgh

Faculty of Social Sciences Staff Seminars

Report No. I

Contents

| TOM BURNS, S. B. SAUL |

| M. W. FLINN |

| EVERETT E. HAGEN |

| REINHARD BENDIX |

| MICHAEL ARGYLE |

The four papers published in this short book were read to a Seminar organized by the Faculty of Social Sciences at Edinburgh University and held at the end of the spring term 1965. We should like to record our indebtedness to the authors of the papers and to the many distinguished people from this country and abroad who attended the Seminar and enriched its proceedings.

The central theme of the Seminar was Professor Hagen's views on the process of social change as expressed in his book On the Theory of Social Change and elaborated further in the paper presented by him to the Seminar. The papers appear in the order in which they were given to the Seminar and are prefaced by a short review in which the organizers attempt to outline some of the main lines of criticism offered in the course of the discussions.

TOM BURNS AND S. B. SAUL

If history is to be more than narrative, then it has to explain. Even as narrative, the historian's selection and ordering of events and attitudes, of successful and unsuccessful actions, of speech and writings can be meaningful only if he observes a set of principles by which he selects and orders. If history, in short, is to be something other, and more, than news, then it is a search for explanation. Historical explanation is a process of simplification, by which a great many diverse things are shown to be connected or similar. This purpose demands that events are shown to be causally connected and, moreover, that the causal principles themselves are ordered according to some hierarchic system. It is in this sense that Collingwood regarded history as a science.

To adduce a multiplicity of causal factors without relating them to each other either burkes the historian's task or, more seriously, misleads by assuming that causes are unconnected with each other and therefore additive: i.e. that the more causes one can find, the better the explanation. The openness of British eighteenth-century society, the freedom with which business associations were entered into with friends and friends of friends or with fellow sectarians, and the wide diffusion through the ranks of society of the perception by early scientists that natural events 'obeyed' natural laws: all three generalizations have entered into discussion of the 'causes' of the Industrial Revolution. Putting them into juxtaposition suggests some logical and empirical link between them. But, if one exists, do not such 'causes' merely operate as dependent variables? Are the three 'causes' (or effects) in fact similar? If so, is there some underlying social, economic, or political factor which 'explains' the coexistence of similar dispositions in these different sectors of eighteenth-century society? Can one rest at the point at which, for example, Landes stops in his brilliant essay on the Industrial Revolution (in Volume VI of the Cambridge Economic History of Europe ) with an enumeration of the institutional factors, economic and social, that were concomitant with the economic and technical changes that occurred in Britain during the critical seventy years of the Industrial Revolution?

The force of the dilemma is perhaps more compelling, or more apparent, in economic history than in political or military history, where, it is said 'most historians are content to leave to the social scientists the attempt to formulate general laws' and where 'the emphasis now is upon the satisfaction of a disinterested curiosity about the past'. In economic history, curiosity takes less deprecatory forms.

Of course, to make sense of such a question as 'Why did the Industrial Revolution occur at the time, and in the place, it did?' is to commit oneself to a bold and possibly presumptuous endeavour. But it is towards such endeavours that the whole of economic history is directed: towards the reduction of the infinitude of historical facts by ordering them in terms of explanatory principles the fewer the better.