Anthem Press

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

www.unionbridgebooks.com

This edition first published in UK and USA 2021

by UNION BRIDGE BOOKS

7576 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK

or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK

and

244 Madison Ave #116, New York, NY 10016, USA

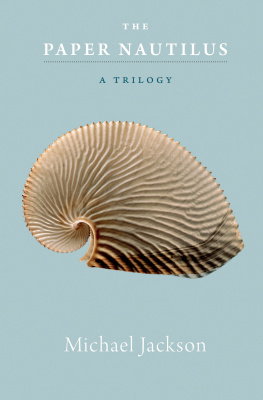

Copyright Michael Jackson 2021

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above,

no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means

(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise),

without the prior written permission of both the copyright

owner and the above publisher of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020949109

ISBN-13: 978-1-78527-641-5 (Hbk)

ISBN-10: 1-78527-641-7 (Hbk)

This title is also available as an e-book.

Caelum, non animum, mutant, qui trans mare currunt

(They change their sky but not their soul who cross the ocean)

Horace

Although we are all occasionally haunted by the past, for some of us the past is not so much another time as another country. And while many people yearn to be young again, others long to return to the places where they were young and the landscapes of their most formative years.

Whether experiencing nostalgia for a lost time, a distant place, or an absent loved one, it sometimes seems that human beings seldom feel completely at home with themselves or at home in the world. The grass may appear greener on the other side, but no sooner have we crossed the bridge to those more promising pastures than the paddocks we abandoned lure us back. Even when we return to the land we deserted, we often find it difficult to resettle or reconnect. Our erstwhile selves have become frozen in time like the spellbound characters in a fairytale. Our lives have morphed into myth or history.

Yet stasis is an illusion. We are always in movement, if not from place to place then from one relationship to another, or from one phase of life to another, and our moods, emotions, and thoughts are in continual flux. Accordingly, leaving ones native land, leaving ones parental home, and losing touch with ancestral places and ways of life may inspire hope for a more fulfilling future or cause deep disorientation and distress.

While my expatriate status undoubtedly explains the kinship I feel for many of the migrants I have come to know, I would not wish to play down the differences between the violent and irreversible circumstances endured by many of them and the relatively comfortable situations of most expatriates. What I do claim, however, is that those who leave their homelands, either under duress or by design, will see them in a different light than those who have stayed put. I hope to show, moreover, that the perspective of the expatriate, exile, or conscious pariah is analogous to what ethnographers call stranger value and implies a more subjective approach to understanding than the traditional scientific invocation of detachment and neutrality, the so-called view from afar.

In my case, this bifocal perspective entails a bicultural one in which I have recourse to Mori traditions of sociality and knowing, not to impose a Eurocentric interpretation on them but to show how cross-cultural conversations and interactions can transform our assumptions about the human condition.

A lot of contemporary discourse, both in the academy and beyond, is predicated on essentialized notions of gender, class, and ethnic identity. In critiquing the eitheror polarizations that characterize identity thinking, I hope to emphasize human plurality as entailing both difference and identity. The assumption here is that, as a species, human beings share the same evolutionary history and confront similar existential dilemmas, yet no two individuals are alike, and very different adaptive strategies and worldviews have emerged in the course of human history. To speak of the human condition, therefore, is to imply that existence is not only replete with contradiction and conflict but also characterized by ongoing struggles to resolve, accept, or overcome them.

The chapters of this book touch on a variety of issues, including the ambiguity of belonging, the struggle for indigenous rights, expatriate experience, the ethics of genetic engineering, experiments in communal living, and intercultural dialogue. These issues have both local and global relevance, and I address them as an expatriate and an ethnographer who has discovered that the anxiety that springs from being an outsider is often compensated for by an ability to see the world from a novel point of view. Moreover, as an outsider, one is sometimes consoled to find that ones dilemmas are not unique. While one may be struggling to adapt to new customs, learn a new language, or cope with bizarre customs and inhospitable surroundings, ones new neighbors may be suffering social exclusion, embroiled in family feuds, fighting prejudice, or coming to terms with the effects of a pandemic, climate change, or economic collapse. Indeed, it is often through such critical experiences that people from diverse backgrounds come to realize that they share a common world.

One in six New Zealanders lives abroad, making our diaspora the second highest in the developed world.was formed in a world of egalitarian values, and they often recoiled from the elitism and pretentiousness of the societies in which they wound up.

Successive generations of New Zealand writers have wrestled with the geographical remoteness, political marginality, and colonial legacy of their homeland. Those born and bred in England suffered what Vincent OSullivan calls a colonial neurosisan obsession with a nation in which they no longer lived and a self-consciousness about what they regarded as New Zealands lack of a cultural heritage. By the 1930s, a preoccupation with a defining national consciousness pervades the work of many writers, but it was not until the 1960s that one begins to see a more confident identification with American and European authors, a diversification of literary styles, and the beginnings of an engagement with Mori points of view. This break with parochialism is partly enabled by a shift from identity thinking to a more eclectic and open-minded attitude in which ones sense of self is never fixed or final but susceptible to ones changing interests and varied experiences. This was brought home to me on a recent visit to Auckland during which Brian Boyd introduced me to Fiona Pardingtons high-resolution photographs of the wings of Nabokovs butterflies. As Brian described his collaboration with Pardington, and the way her bicultural heritage found expression in the diversity and ingenuity of her creative projects (recovering dead material for contemporary reflection, from plaster casts of Mori heads, to birds, mushrooms, and bottles), I was struck by the vital cosmopolitanism of her work and the close connection between creativity and double consciousness.