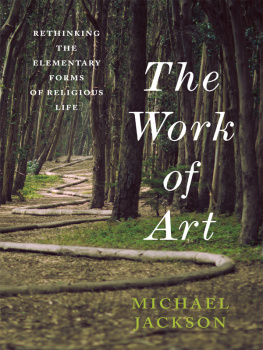

Published by Otago University Press

Te Whare T o Te Wnanga o takou

Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2019

Copyright Michael Jackson

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-98-853179-3 (print)

ISBN 978-1-98-859289-3 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-98-859290-9 (Kindle mobi)

ISBN 978-1-98-859291-6 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Editor: Erika Bky

Design and layout: Fiona Moffat

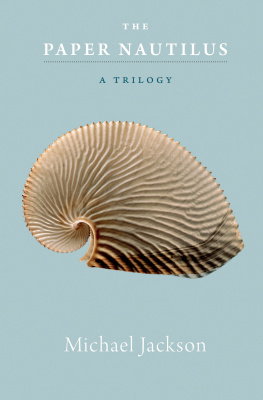

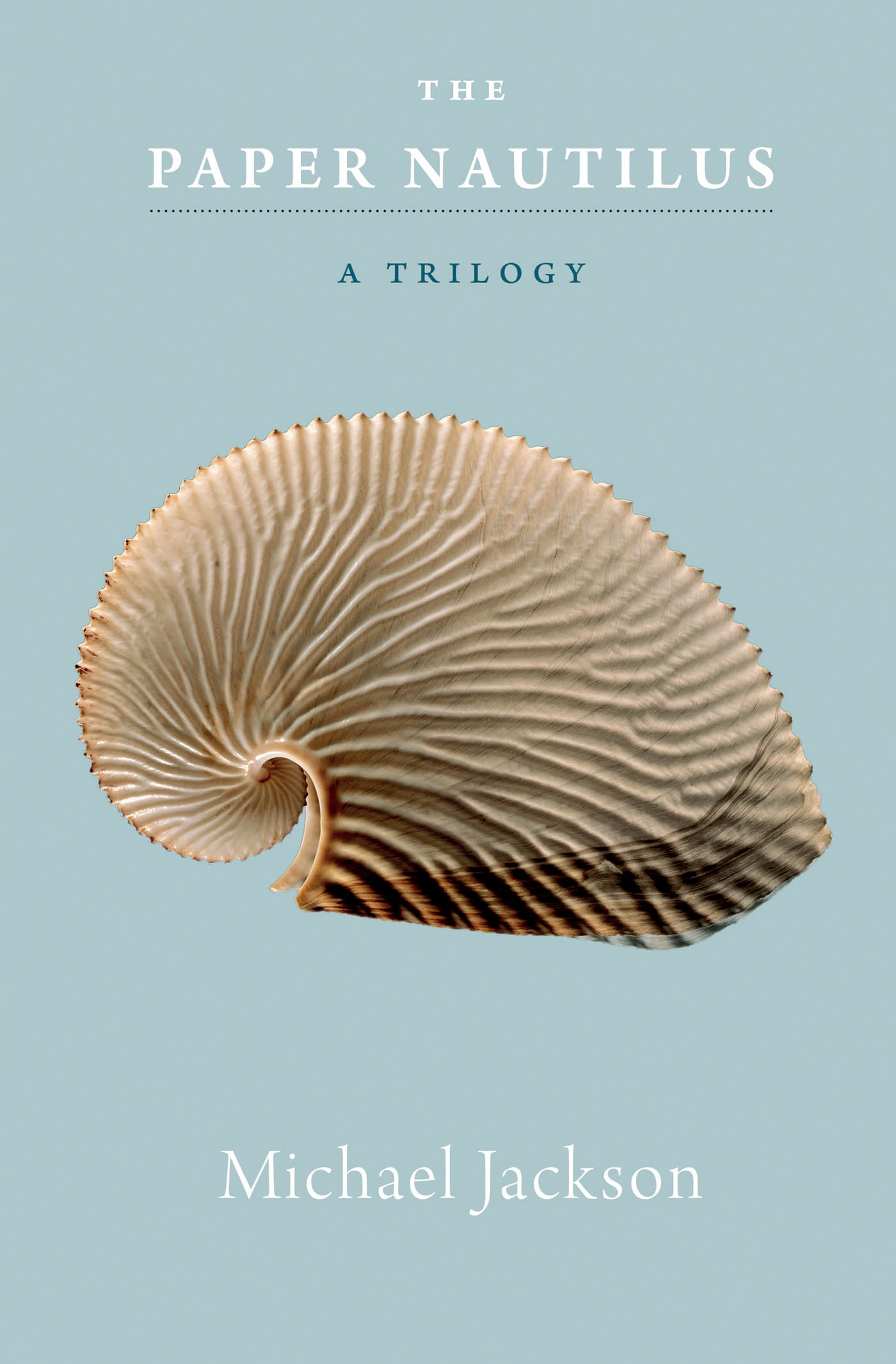

Front cover: Argonaut Octopus Eggcase Shell, Gilles Mermet

Science Photo Library, C019/1291

Ebook conversion 2020 by meBooks

And so a mix of truth and fiction, however unsatisfactory in philosophical terms, offered by somebody who is trying, with all the intelligence, sympathy and understanding of which they are capable, to imagine the situation of the other person from the inside out is worth far more than a pure and lonely truth. An I-and-you truth, a relational truth, is much more valuable than one more separate and more certain.

ARABELLA KURTZ, The Good Story

CONTENTS

1.

THEME AND VARIATIONS

LOSING THE PLOT

Ive always been drawn to two literary genres the picaresque and the frame narrative. As a child I was entranced by the artful way in which Scheherazades stories in The One Thousand and One Nights were set inside one another like matryoshka dolls. Equally intriguing to me was the way her stories were connected not by logic but by adventitious associations. In my fieldwork in Sierra Leone I was again captivated by tales whose chaste compactness, to use Walter Benjamins phrase, belied their existential depth. While picaresque and frame stories bear a family resemblance to classical folktales, they are very different from the novel, a genre that emerged in the eighteenth century. Centred on individual subjects and characterised by complex plots, the novel is more akin to the academic essay than to the folktale, which was subsequently denigrated as infantile and premodern. For me, one appeal of the traditional tale is its unapologetic acceptance of the role of contingency and coincidence in human life. While the novel reflects a modernist ethos of possessive individualism, which foregrounds conscious purpose, complicated motivations and emotional compulsions, the unfolding of the traditional tale depends on happenstance, fate and caprice.

Although elements of the frame narrative and the picaresque find expression in modern cinema, I yearned to create a work in which variations on a theme would replace the adventures of a person. My theme is loss: the forms it takes and how we go on living in the face of it. When I reflect on the vicissitudes of my own life or my ethnographic experiences in West Africa, I am struck by the mysterious ways in which new life and new beginnings are born of brokenness. The paper nautilus provides a vivid image of this interplay of death and rebirth. A fragile shell buoys the eggs of the pelagic octopus to the surface of the sea, whereupon it is blown into inshore waters. There the angelically beautiful brood chamber breaks, the eggs hatch and the baby octopuses begin their life cycle.

But how was I to write about a theme that finds such a bewildering variety of expressions in different societies, individuals and genres? How could I do justice to this phenomenological diversity?

I took heart from David Lynchs account of wanting to create a certain kind of film but needing to let his ambition become a bait, luring ideas to him as fish are lured to a hook. By implication, ideas, images and even people come to us unbidden, and slip away from us just as unpredictably, as if obedient neither to necessity nor convention, and indifferent to whether we are worthy or unworthy of their presence. I also found inspiration in Alan Bennetts Untold Stories, a copy of which had been discarded on a pew near my office at the Harvard Divinity School. I read it as if it were a gift from the gods and considered keeping a commonplace book in the hope that I might be party to the kind of aperus that seemed to fall fortuitously into Bennetts lap. In any event, I was curious to know the extent to which life itself may determine the path of ones thinking and the form of ones writing, and whether aimless wandering, daydreaming, unexpected encounters and free associations can open us up to the world in ways that conscious planning cannot.

There are times when the self splinters under the pressure of displacement and loss. One becomes multifaceted. I becomes an-other. Invented characters give voice to experiences one hesitates to acknowledge as ones own, and genres blur, as if none can do ones subject justice. Accordingly, this work begins discursively with a series of loosely connected essays and gradually morphs into a memoir of a marriage and a friendship, only to be reinvented as a work of fiction.

LOST FORTUNES

Yesterday the Dow plunged more than a thousand points. Apparently such ups and downs in the money markets are not unusual, and right now the markets are adjusting to a period of accelerated economic growth, rising inflation and a somewhat more hawkish Federal Reserve. According to one analyst, these typical late-cycle trends have generally been good for stocks.

Its not only the market thats volatile. Life too has its cycles of boom and bust, and also, perhaps, a capacity to self-correct. As for the clichs with which stockbrokers reassure their panicking clients Diversify, Rebalance periodically, Dont try timing the market, Stay focused on the long term, Have a rainy-day fund on hand, Talk to your financial advisor they are uncannily like the hackneyed phrases with which we console those whose lives are falling apart.

In life as in the marketplace, you never know when, or in what way, the rugs going to be pulled from under you when your best efforts may come to nothing; when the things you once did without a second thought may become Herculean tasks; when you may be driven from your home by war and must cross a border to a place where you are not wanted, to await a return that may never be possible. When you lose someone you love. When age, illness and infirmity erode your hold on life, and no pleasure outweighs your pain.

Writing about neurological deficits, such as loss of speech, language, memory, vision, dexterity and identity, Oliver Sacks observes that a disease is never a mere loss or excess that there is always a reaction, on the part of the affected organism or individual to restore, to replace, to compensate for and to preserve its identity, however strange the means may be. He goes on to say that the study of these curious ways in which life goes on is an essential part of a physicians vocation. This is also true of a writers work. What interests me, however, is not how we make good our losses but how we learn to live with them. Sacks was inspired by the pioneering work of the great Russian neuropsychologist A.R. Luria, who, in

Next page