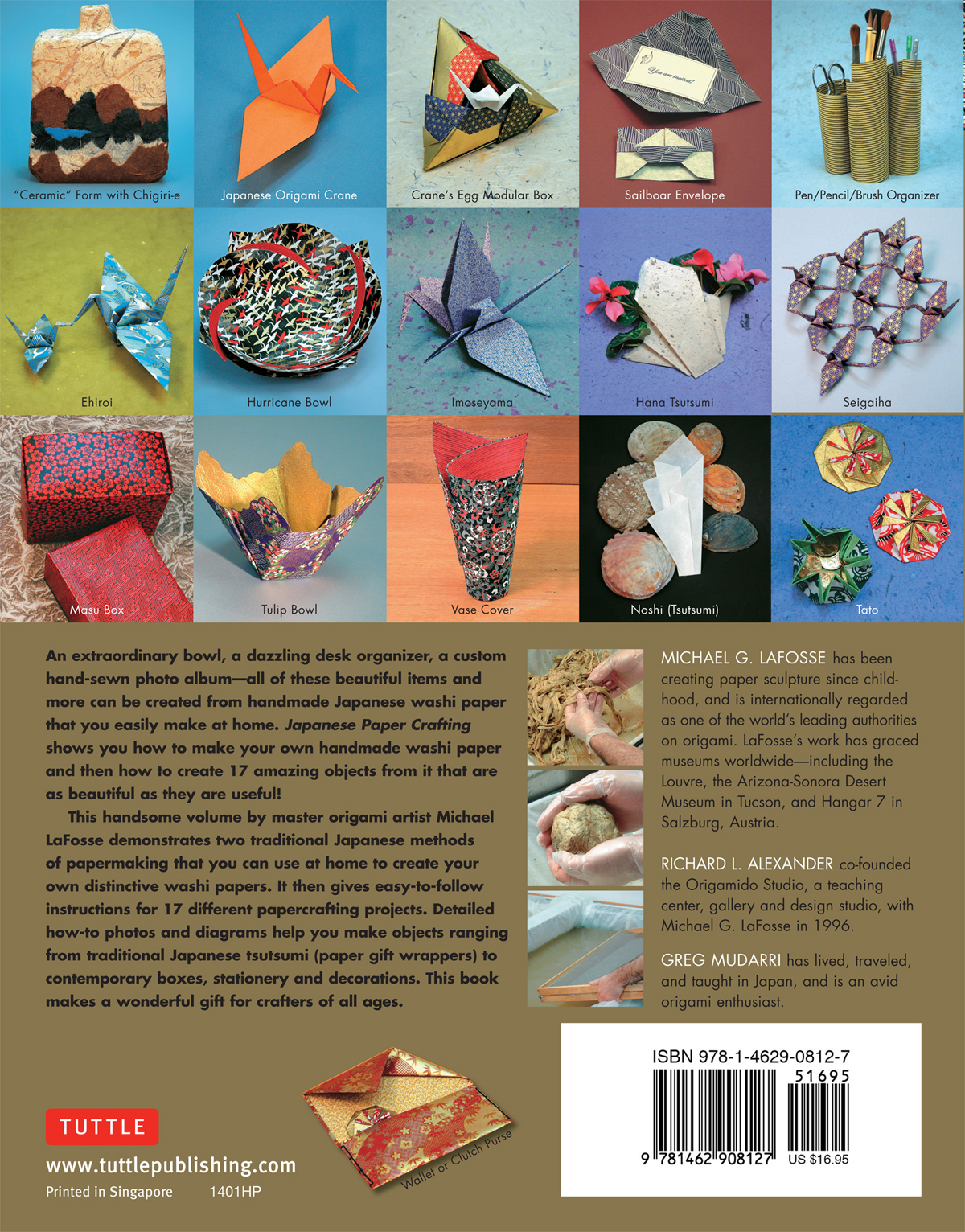

T his book would not have been possible if not for the help and input from Richard L. Alexander and Greg Mudarri, my colleagues at Origamido Studio. They helped me with the text, the photos, and even the selection, design, and testing of the projects.

First, I would like to thank Richard, my partner and co-founder of Origamido Studio, who took over many of the origami teaching duties as I worked out the diagrams and the how-to steps. He also took most of the photographs, juried the projects, and helped select the washi we used to make them.

I am also indebted to Greg Mudarri, who had recently returned from a fifteen-month stay in Japan where he was teaching English and folding paper. Greg had been studying and working with us since 2003, so he was able to jump right in and lend his expertise for the presentation of the traditional projects that I wanted to show in this book, including the Noshi and Senbazuru projects.

Finally, I would like to thank Holly Jennings and Sandra Korinchak, senior editors at Tuttle Publishing, for their patience and guidance through the process. Tuttle has been a great friend to people who love fine paper, paperfolding, and the simple elegance of traditional Japanese culture. I am grateful they gave me the opportunity to create such an interesting collection of beautiful, useful, and fun projects.

BIBLIOGRAPHY & RESOURCES

All Japan Handmade Washi Association. Handbook on the Art of Washi . Tokyo: Wagami-do, K.K., 1991.

Araki, Makio. Nihon no Orikata Shuu [A Collection of Japanese Folding Methods]. Kyoto: Tankousha, 1995.

Barrett, Timothy. Japanese Papermaking: Traditions, Tools, Techniques . New York: Weatherhill Inc., 1992.

Farnsworth, Donald. Momigami . Oakland, CA: Magnolia Editions, Inc., 1997.

Hughes, Sukey. Washi, The World of Japanese Paper . New York, Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1978.

Hunter, Dard. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft . New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1943. Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1978.

Keeton, William T. Biological Science . New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1967.

LaFosse, Michael G. Advanced Origami: An Artists Guide to Performances in Paper. Rutland, VT: Tuttle Publishing, 2005.

LaFosse, Michael G. Paper Art: The Art of Sculpting with Paper . Gloucester, MA: Rockport Publishers, Inc., 1998.

Carriage House Paper

79 Guernsey Street, Brooklyn, NY 11222

Donna Koretsky

www.carriagehousepaper.com

Carriage House Paper Museum and Research Institute of Paper History & Technology

8 Evans Road, Brookline, MA 02445

Elaine Koretsky

www.papermakinghistory.org

Dieu Donne Papermill

315 West 36th Street, New York, NY 10018

www.dieudonne.org

The Friends of Dard Hunter, Inc.

P.O. Box 773, Lake Oswego, OR 97034

www.friendsofdardhunter.org

Origami USA

15 West 77th Street, New York, NY 10024

www.origami-usa.org

Origamido Studio

www.origamido.com

WASHI

The Magnificent Skin of Japan

T he word washi is a combination of two Japanese words, wa and shi . Taken literally, wa means peace, and shi means paper. However, when used together, they have come to mean Japanese paper, with the wa prefix now representing the essence of Japanese culture. Nowhere else but in Japan does a culture seem so intimately associated with fine papers. For centuries, the Japanese have embraced the exploration of papers potential. Through this exploration, they soon realized that washi could become so many things, including clothing, lanterns, parasols, fans, windows, room screens, masks, and ceremonial decorations.

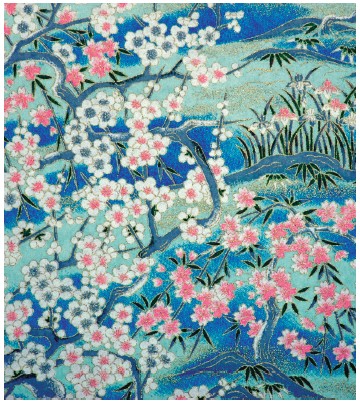

Japanese handmade papers are as beautiful, genuine, and interestingly varied as Japan itself. The patterns chosen to decorate washi are typically icons of the rich Japanese culture, landscape, and history. Like washi, Japan can show its bright colors, bustling noise, and excitement, but it can also show its softer, natural, tranquil side. From bright, silk kimonoinspired Yuzen patterns to subdued, creamy, silky whorls, washi offers a magnificent skin that expresses and defines Japan.

Washi is beautiful, not only on the surface but throughout: Washis inherent character tends to shine through, even when its surface is printed, painted, or dyed. Its simple beauty belies the extraordinary effort taken to create luxurious paper with soft and supple strength.

Washi is not only beautiful but endlessly varied. Its raw materials are products of the Earth, and the three major species of plants harvested to become washi Kozo, Mitsumata, and Gampiare each unique, making their own inimitable contribution to the final product. Geography, topography, and local weather conditions affect these plants, which can grow quite differently in the various regions of Japan, and add to the individual personalities of the paper. These subtle differences in fine papers, like scrumptious foods and exquisite wines, do indeed enhance a civilized life. The Japanese people have long realized this and seem to respect high-quality paper perhaps a bit more than others do. So I call washi the magnificent skin of Japan for these reasons, but you do not have to be Japanese to appreciate, make, or use washi.

THE SPECIAL QUALITIES OF WASHI

There are countless different kinds of washi, yet there are certain recognizable qualities that set it apart from similar, western-style papers. People who encounter washi for the first time remark that it resembles cloth more than it does paper, which is probably a fair assessment due to its softness, both in look and feel. Although washi may feel soft, if made correctly it is exceedingly strong, even when wet. Its folding and tensile strength measurements are often quite high, due to the length and quality of the fibers. Its strength allows washi to be employed as a basic material for fabricating a staggering range of durable, utilitarian, and decorative items.

The overriding element that makes washi so different from other paper is that washi has a refined beauty, found even in its coarser forms. Certainly, some of this special beauty results from the care in selecting, harvesting, handling, and processing the fiber, but much comes from the skill of the papermaker. Most agree that the painstaking labor of making washi by the time-honored, traditional hand methods results in paper that reveals the inherent honesty of the materials. Soetsu Yanagi wrote, in Washi no bi (The Beauty of Washi), The more beautiful it is the more difficult it is, to make trivial use of it. This is perhaps the greatest stumbling block for most people who love and purchase washi: It is too beautiful to use! Sure, you can frame it, or just keep it in drawers and look at it every so often, but washi begs to be used, and this book presents a series of delightful projects that can help you provide a suitable stage for its full appreciation.

Most people limit their thinking about using washi to simply wrapping or covering things, but with some clever techniques washi comes alive with shape and form. Even artists and craftspeople who routinely use other paper in their work enjoy the qualities of washi, yet they often avoid it because of its softness, opting for stiffer, machine-made papers. The fact is that, even though most washi wears quite well, it often must be lined, backed, or stiffened before use. This book will show you how to prepare your washi for all manner of applications. This and other essential preparation techniques will allow you to greatly expand the possibilities for using washi in your artwork or incorporating it into your surroundings to liven up and enrich your everyday life at home or at work. These techniques are not complex, but few books explain them. No wonder so much of the finest papers sit unused in the dark.