INTRODUCTION

By Richard Alexander

A n article was published in a 1970 Readers Digest about Akira Yoshizawa, an inspired paper-folding artist from Tokyo. Thirty-two years earlier, at the age of 26, he had quit his job at an iron foundry, and decided to devote the rest of his life to creating origami art. Michael LaFosse was a fourteen-year-old living in Fitchburg, Massachusetts when he first saw that article with compelling photos of Yoshizawas remarkable, lifelike creations. As he read intently about this whole new world of origami art, Michael decided he too would be an origami artist.

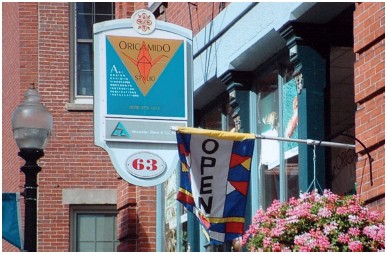

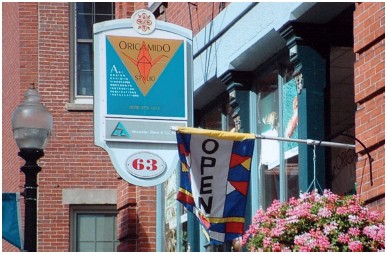

What Michael and Yoshizawa had in common was a fascination for transforming a single square piece of paper into something wonderful. Each had been captivated at an early age by their ability to express artistic creativity through the process of folding paper. Each had been frustrated by the simplicity of the traditional models. They wanted more. The article mentioned that Yoshizawa dreamed of establishing a museum and research center to extend the benefits of origami to the world. In 1996, Michael and I opened the Origamido Studio to the public to do just that.

The earliest documented process for making paper was developed in China in the second century A.D. Paper folding possibly spread with paper along the trade routes to Japan and Europe, models being taught by one person to another. Early folded designs were surely utilitarian, then ceremonial. Paper-folding designs practiced in Europe and Asia probably resulted from alternating periods of sharing, then isolation with considerable independent development. Until the Industrial Revolution, paper was likely too precious to be folded for fun. Until the communications revolution, and for nearly two thousand years, the complexity of the folded paper designs was limited by the teachers ability to pass on the various folding sequences.

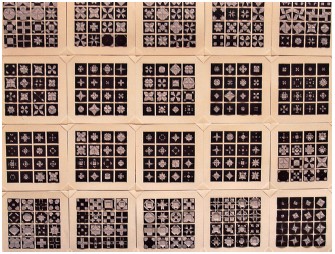

Yoshizawa had only six years of formal schooling, but his school years occurred when the world was being swept by a new educational curriculum for young children, originally developed by a German named Friedrich Froebel. His Kindergarten incorporated the exercises of folding paper squares into different shapes and patterns as an educational tool. Scholars credit the current, international use of the word Origami to the translation of the words Papier Falten (paper folding) from German Kindergarten textbooks, introduced to Japan around 1900. Scholars credit the export of the Froebellian Kindergarten system to Japan, and the subsequent translation of instructions for teachers, for the beginning of the current, international use of the Japanese word, Origami. The traditional Japanese paper folding repertoire, before the time of Yoshizawa, probably numbered fewer than 100 models. Until the introduction of Kindergarten in Japan, paper folding was essentially relegated to the crafting realm of grandmothers and their granddaughters. The formalization of paper folding in elementary schools, thanks to their adoption of the European system, helped legitimize and broaden the Japanese understanding of this craft as a useful learning tool, and not just a trivial pastime.

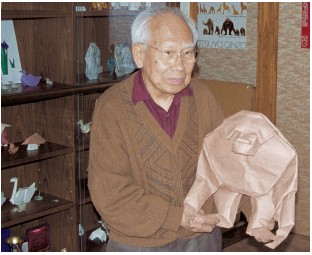

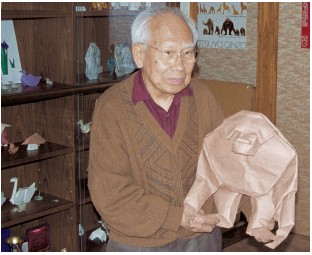

Akira Yoshizawa in his Tokyo studio, holding his Origami Gorilla.

Origamido Studio on Wingate Street, Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Kindergarten seems to have spurred the Japanese to revisit and further explore their traditional and ceremonial folded paper models, embracing paper crafts with more excitement than the Kindergartens of the USA or Europe. Along with Kindergarten came inexpensive, mass-produced squares of colored folding papers. Until Yoshizawa, folding paper was considered a Kindergarten craft and pastime. By the time the Readers Digest article was written, Yoshizawa was 58 years old and claimed to have created and saved some 20,000 origami models in his house. Some would say that he alone has been responsible for the birth of a true and significant folk art.

Yoshizawa claims to have never sold a piece, being so passionately involved in their creation, he considered his origami models as his children. Both Michael and I have traveled to Tokyo and watched Yoshizawa retrieve, unwrap, contemplate, then re-wrap and store dozens of his favorite pieces. It was easy to see why he did not sell those breathtaking works, not only because they were his children, but because they represented so much work and personal, emotional investment, that no price was ever high enough. Even the simplest models clearly showed the artists touch the unique magic of paper art.

We want the Origamido Studio to help develop a deeper understanding, and hence, a better appreciation for this new artto help people understand why certain models are significant, perhaps because of their technology, history, development, and provenance; but also because of their elegant beauty, and how through them, the artist is able to speak to our souls.

Origami art as a recent development is indeed a strange type of art. Imagine Rembrandt writing a book about how to paint a dozen of his luminescent masterpieces. Or imagine Michelangelo recording a video about how to carve his glorious Pieta. At the Origamido Studio, Michael has often used the analogy of music to explain that the art of origami not only requires the designer (composer), but talented and skilled folders (musicians), using the most superb instruments (handmade paper), and practiced technique. In this light, we offer this additional set of diagrammed projects for yet more complex origami art models requiring advanced folding skill sets, and of course, an artists vision.

Our first hardcover book devoted solely to origami art, Origamido: Masterworks in Folded Paper (Rockport Publishers) was primarily a book of photos of a spectrum of contemporary origami models by forty international living masters. As such, it was the first of its kinda coffee table book serving as an origami art exhibit between boards.

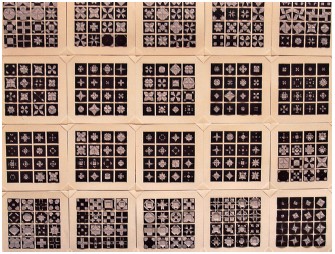

Friedrich Froebels Kindergarten patterns of folded papers.

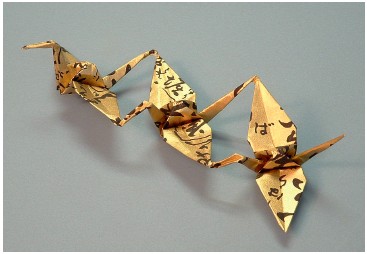

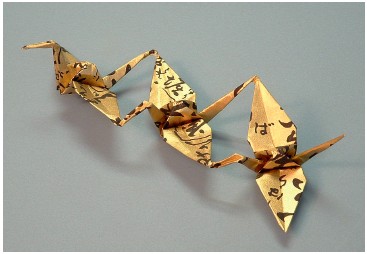

Traditional Senbazuru of Three Connected Cranes. Folded by Greg Mudarri.

Traditional Japanese Ceremonial Noshi folded by Greg Mudarri.

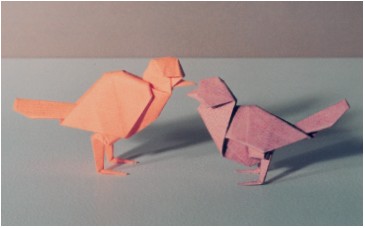

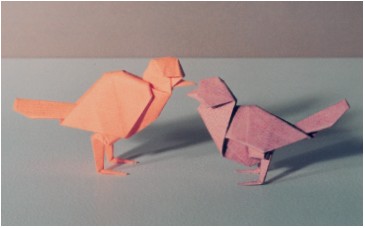

Akira Yoshizawas origami birds.

Michael had coined the word Origamido when he was a teenager, to distinguish the art of origami represented by Yoshizawas amazing work from the pastime of simple folded paper amusements. Ori is from oru, meaning to fold; gami from kami, meaning paper; and the suffix do referring to the way, path, experience or journey of following a prescribed discipline.

Many of the models shown in Origamido: Masterworks had been only recently displayed at a special exhibition at the Carousel du Louvre, in Paris. Until then, only a relatively few origami aficionados attending conventions saw these works up close and in person. The Origamido: Masterworks book brought exquisite origami art to thousands. Several of these artworks also went on display at the Mingei museum in San Diego, thanks to the dedication and hard work of VAnn Cornelius and others. The show was so popular, it was extended, and another version of the show was set up for an additional stay in a satellite facility.