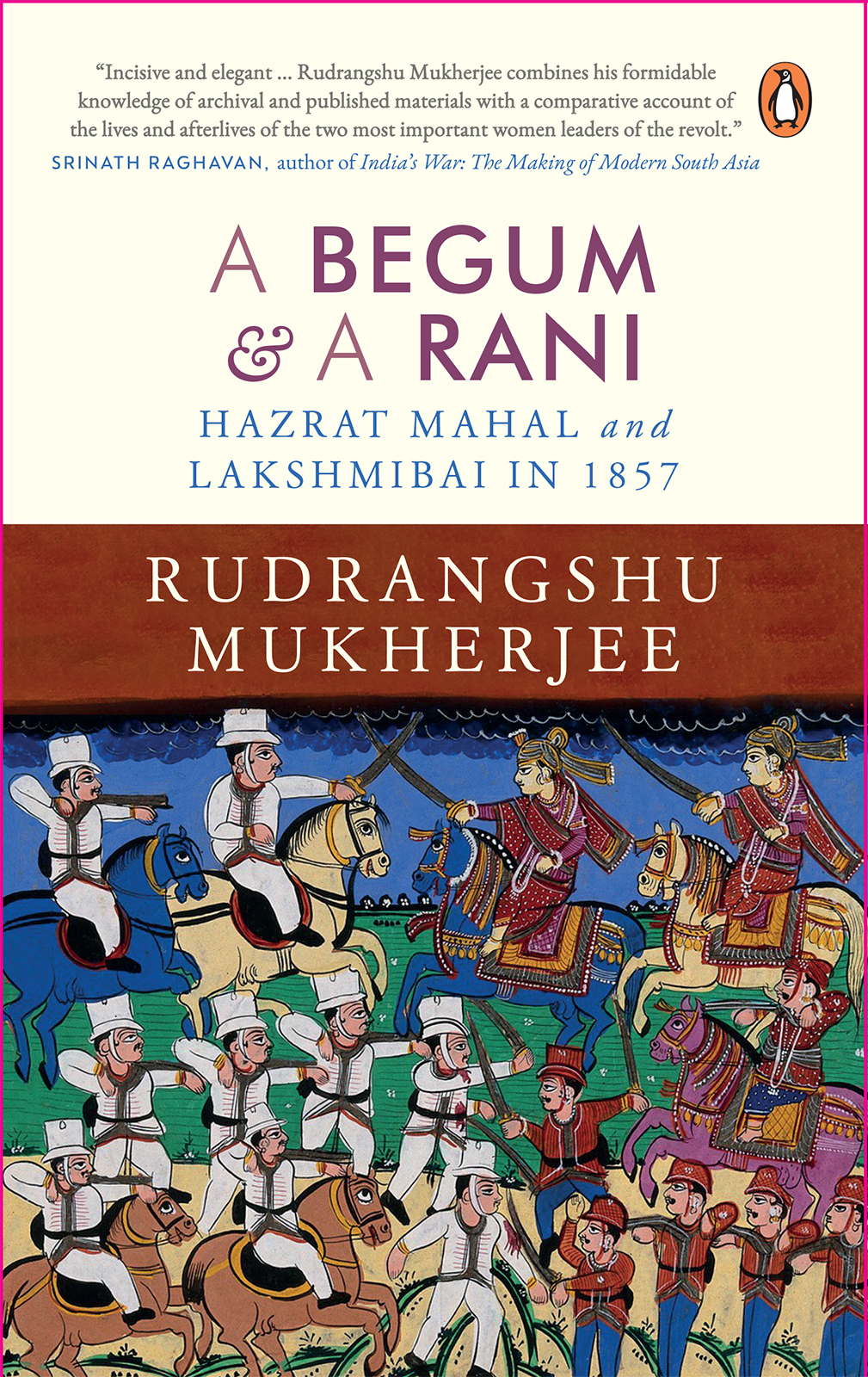

Rudrangshu Mukherjee - A Begum & a Rani

Here you can read online Rudrangshu Mukherjee - A Begum & a Rani full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Penguin Random House India Private Limited, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Begum & a Rani

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Random House India Private Limited

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Begum & a Rani: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Begum & a Rani" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Begum & a Rani — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Begum & a Rani" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

To the memory of two Lucknow personalities,

Ram Advani and Mohini Mangalik

May these characters remain

When all is ruin once again.

- Cons.: Consultations

- For. Dept.: Foreign Department

- Forrest, Selections: Selections from Letters, Despatches and State Papers in the Military Department of the Government of India, 185758, 4 vols (Calcutta: Government of India: 18931912).

- FSUP: Rizvi, S.A., and Bhargava (ed.), Freedom Struggle in Uttar Pradesh (Lucknow: Publications Bureau: 1957; repr. Delhi: Oxford University Press: 2011).

- IOR: India Office Records in the British Library, London.

- Kaye: Sepoy War, Kaye, J.W., History of the Sepoy War, 3 vols (London: W.H. Allen: 18641876).

- NAI: National Archives of India, Delhi

- NWP: North-Western Provinces

- Proc.: Proceedings

- Sec/Secy: Secretary

- Suppl.: Supplement

In Bertolt Brechts play The Life of Galileo, there is a significant scene towards the end. It takes place on 22 June 1633 and is set in the palace of the Florentine ambassador in Rome. Galileo has been taken away to appear before the Inquisition. On stage are his three pupils, Andrea, Federzoni and the little monkall eagerly waiting for news and hoping that Galileo will not recant his views. Also present is Virginia, the scientists daughter, who is praying that her father will recant and thus not be damned. The announcement will be made by ringing the bells of St Marks. The bells begin to toll, and the voice of the crier is heard saying that Galileo has renounced his belief in a heliocentric universe and has accepted the teachings of the Holy Church. The directions in the play read: The stage grows dark. When it grows light again the bell is still tolling, and then stops. Virginia has gone. Galileos pupils are still there. Andrea says loudly, Unhappy the land that has no heroes! As he says this Galileo enters, completely altered by his trial, Brecht writes, almost to the point of being unrecognizable. He has heard Andreas last sentence. For a moment he pauses at the door for someone to greet him. As no one does, for his pupils shrink back from him, he goes slowly and unsteadily because of his failing eyesight, to the front [of the stage] where he finds a stool and sits down. Brecht has Galileo say in response to Andrea, No. Unhappy the land that is in need of heroes.

Under British rule that followed military conquest, India was an unhappy land. The unhappiness of the common people was rooted in their poverty, which was a result of British exploitation. Among western-educated Indians, it stemmed from the realization that their past had been taken away from them, that British rulers had appropriated the Indian past. James Mill famously announced this act of appropriation in his book The History of British India, where he wrote, The subject [Indian history] forms an entire, and highly interesting, portion of the British history.

Western education brought to the new intelligentsia a new awareness of its own past. Colonial educationin institutions like Hindu/Presidency College in Calcutta or Elphinstone College in Bombayhad imparted lessons on the rational reconstruction of European history. However, when members of this intelligentsia turned to the history of their own country, they found that history to be written entirely from the British point of view. That past, in the writings of the British, carried a stigma: it was the tale of kalanka, of slander. Yet research by scholars associated with The Asiatic Society of Bengal pointed to an Indian past that was rich in philosophy, literature, political institutions and economic development. Sections of the western-educated literati, in the second half of the nineteenth century, took on the project of recovering the Indian past and freeing it from the biases and prejudices of British writers. This project was nothing less than an attempt to reconstruct an autonomous history of India. It was also informed by a sense of pride in ones own country and a sense of belonging. The writing of history became the domain where patriotism began to first assert itselfa pulling away, in the words of Ranajit Guha, from servility, however feebly, towards an assertion of independence. It was also an attempt to step out of the state of unhappiness to the state of pride in ones motherland.

Given the state of history writing in the nineteenth century, it is not surprising that the attempt to represent Indias past was based on individuals or what is often called the great man theory of history. It is significant that the first three books on history to be published in Bengali were books based on individuals. Two of themRaja Pratapaditya Charitra by Ramram Basu, published in 1801, and Maharaj KrishnachandraRayasya Charitram by Rajiblochan Mukhopadhyay, in 1805dealt directly with individuals. Rajabali by Mrityunjay Vidyalankar, published in 1808, was about the Rajas and Badshahs and Nawabs who have occupied the throne in Delhi and Bengal. India had its own history; the foreign rulers had obliterated it. That history had to be retrieved. The nineteenth century and the early twentieth century saw many such acts of historical retrieval in different parts of the countryall intellectual exercises to write an Indian history of India.

For the purposes of this book, none was more important than a short essay on the Rani of Jhansi published in 1877 by a sixteen-year-old Rabindranath Tagore, who was already making a name for himself in the literary world of Calcutta. Tagore began the essay, simply titled Jhansir Rani (Rani of Jhansi), by recalling the bravery of the Rajputs and the patriotism of the Marathas, which many believed had been extinguished under 1000 years of slavery. The history of the revolt of 1857 (Tagore called it Sipahi Yuddha or Sepoy War) had shown that such a conclusion was unwarranted. He wrote that the special virtues of these people had been asleep and subsequently woken up during the revolution. He drew attention especially to the courage and military achievements of Tantia Tope, Kunwar Singh and Rana Beni Madho of Sankarpur. If these and other heroes (vira) had been born in Europe, Tagore wrote, they would have been immortal in the pages of history, in the songs of poets, in sculptures and in monuments and memorials. However, in India, in the hands of British historians, the stories of these heroes were written in the most ungracious manner. Tagore added that these versions, too, would be washed away in time, and their lives would be unknown to future generations. Of the all the Indian heroes of 1857, Tagore drew special attention to one individual: the woman of valour (virangana), Rani Lakshmibai, the Queen of Jhansi, before whom we must bow our heads in reverence. Tagore went on to depict her as the epitome of virtue: she was young, a few years over twenty, beautiful, strong in body and determined in her mind. She was endowed with a sharp intelligence and comprehended very well the complex issues of ruling and administration. British administrators, as was their wont, Tagore noted, had spread many canards about her character but historians had conceded that not a word of them was true. Tagore described how badly Lakshmibai had been treated by Lord Dalhousie. She had nurtured these grievances and when she heard that the

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Begum & a Rani»

Look at similar books to A Begum & a Rani. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Begum & a Rani and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.