Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

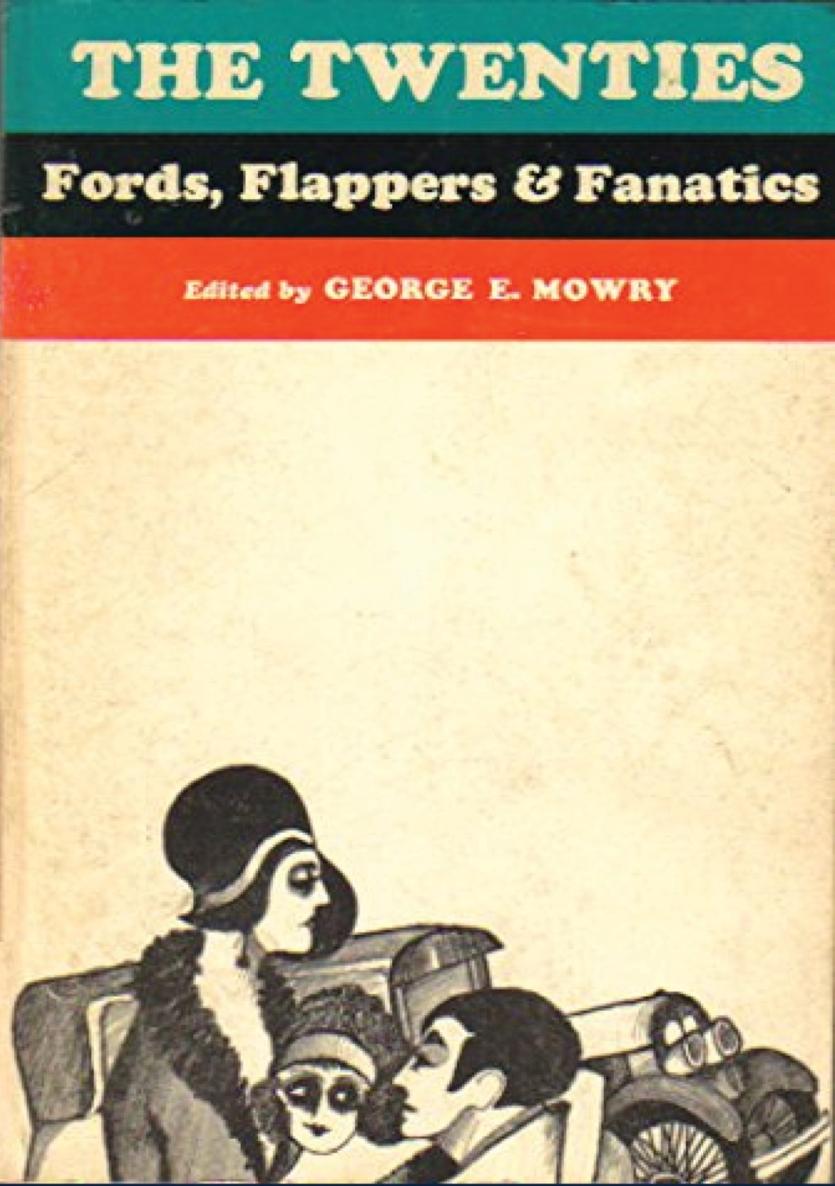

THE TWENTIES

Fords, Flappers & Fanatics

Edited by

GEORGE E. MOWRY

Table of Contents

Contents

Table of Contents

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

DEDICATION

For Vera Pauline Halfhill

INTRODUCTION

The 1920s have often been described by historians as retrograde years, in which little happened except the economic excesses which brought on the depression of 1929. Such an evaluation is due perhaps to the fact that most historians have concentrated chiefly on politics and, compared with either the progressive years that preceded or the New Deal reforms that followed, the Twenties do indeed look sterile. As a matter of fact, the period was one of amazing vitality, of social invention and change. And perhaps it is not too much to say that the Twenties were really the formative years of modern American society. It was during these years that the country first became urban, particularly in the cast of its mind, in its ideals, and in its folk ways. Interwoven and interacting with this change was an amazing technological development and the rise of a new type of industrial economy typified by mass production and mass consumption. Both factors speeded the breakdown of old habits and patterns of thought and prepared the way for the future. The new economy, dependent in the last analysis on the tastes and the acceptance of the crowd, had incredibly important influence upon such widely separated areas as religion, political philosophy, folk ways, dress, moral precepts, and the uses of leisure time.

Until the twentieth century, despite the more or less democratic political apparatus, the countrys social goals and aspirations had been traditionally set by small groups of preachers, politicians, lawyers, editors, and teachers, and later as well by the economic elite spawned by post-Civil War industrialism. But from 1920 on, the tastes of the crowd became an increasingly important determinant, first in popular culture and later in political and economic institutions. And this new mass culture differed vastly from the traditional culture that had been inspired from above.

Societies do not give up old ideals and attitudes easily; the conflicts between the representatives of the older elements of traditional American culture and the prophets of the new day were at times as bitter as they were extensive. Such matters as religion, marriage, and moral standards, as well as the issues over race, prohibition, and immigration were at the heart of the conflict. This cultural conflict is really the central theme of this volume. The division of the sections, as well as the selection of the documents in each section, was made to bring out its salient aspects.

Since this volume deals only with the rise of mass culture, no effort has been made to depict the very rich activity of these years in art, literature, and more formal thought. Most social criticism, by the way, was and has remained extremely critical of the new cultural mix developing during the Twenties. But such criticism often makes little attempt to understand. And it is to be hoped that the following documents will cast light not only upon the origins of this new American society but also upon how and why it arose.

These documents were all written between the World War I and the Great Depression; many were written either by participants in the events described or by firsthand witnesses. They are thus in a way original sources. Perhaps in their totality they will destroy the myth that the Twenties was an unproductive decade and reveal it instead as one of the major formulative epochs in American history.

LET THEM EAT CAKE

The years from the end of World War I to 1929 were a time of phenomenal economic progress and change. During this period the new gospel of mass production, the amazing advances in technology, and the increasing efficiency of labor accounted for a total gain in industrial production of over sixty per cent, far outstripping the gain in population. Consequently, profits, dividends, salaries, and industrial wages all rose appreciably. With the enormous extension of consumer credit and the new emphasis upon advertising and salesmanship, the consumption level of the average American family soared. By 1928 President Hoover could talk without fear of being ridiculed about the possibility of ending all want and poverty. For the first time in world history the masses of a great nation had not only bread but cake. It is small wonder that until the crash of 1929 business and the businessman were venerated.

How this materialist Eden came about is the theme of this section. The aspirations heralded by the cult of business, the operations of the new advertising industry and the profession of salesmanship, the forces behind the rapid extension of mass consumer credit, together with their social implications, and especially the rise of the speculative (expansionist) spirit are all explored in these articles and documents.

1. BUSINESS AS THE NEW AMERICAN RELIGION

As production, profits, and personal consumption standards rose dramatically during the Twenties, faith in business as a way of life spread throughout the nation. But the business creed was not rationalized in material terms alone. A mystique developed making claims to manifold ethical and humanitarian values for business life. Lavish praise of big business as an ethical and social agent may explain the bitter criticism of it during the Thirties when it failed to produce even a living for Americans. But during the prosperous Twenties the broad claims of the following article were not atypical. Edward Earl Purinton, Big Ideas from Big Business, The Independent, April 16, 1921, p. 395.

AMONG THE NATIONS OF THE EARTH TODAY AMERICA STANDS FOR ONE idea: Business . National opprobrium? National opportunity. For in this fact lies, potentially, the salvation of the world.

Thru business, properly conceived, managed and conducted, the human race is finally to be redeemed. How and why a man works foretells what he will do, think, have, give and be. And real salvation is in doing, thinking, having, giving and beingnot in sermonizing and theorizing.

I shall base the facts of this article on the personal tours and minute examinations I have recently made of twelve of the worlds largest business plants: U.S. Steel Corporation, International Harvester Company, Swift & Company, E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company, National City Bank, National Cash Register Company, Western Electric Company, Sears, Roebuck & Company, H. J. Heinz Company, Peabody Coal Company, Statler Hotels, Wanamaker Stores.