Mary Cable - Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties

Here you can read online Mary Cable - Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: New Word City, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties

- Author:

- Publisher:New Word City

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mary Cable: author's other books

Who wrote Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The first day of January 1877, dawned frigid and gray over New York City. It had snowed a few days earlier, and the weather report said it would snow again later that day, heavily. In the greater part of the city, few lights winked on before the dark faded, and there was none of the usual early din of cartwheels and horses hooves. New Years Day being one of only three full holidays in the year (the others were Christmas and the Fourth of July), most citizens welcomed the chance to lie abed late.

On Wall Street, the Stock Exchange was as silent as nearby Trinity Churchyard, where the graves of once-important merchants and businessmen lay under crusted snow. Above Fifty-Ninth Street, the Irish squatters who lived in shanties on the empty lots had sealed their windows and doors with newspapers and taken their goats inside with them. No ferries or small craft plied the bridgeless waters of the East River or the Hudson. And at the Battery, immigrants at Castle Garden would have to wait another day before venturing into the solid-gold streets of New York. From the decks of newly arrived ships, they could see only the vague outlines of many tall buildings - some as tall as seven stories.

But in the fashionable part of New York - in the brick rowhouses of Washington Square and the brownstone blocks that lined and flanked Fifth Avenue all the way to the Fifties - gaslights were burning before dawn. At 21 West Nineteenth Street, Dr. and Mrs. John Frederick May were in the dining room by half-past seven, fortifying themselves with oatmeal and cream, steak and potatoes, baked beans, griddlecakes, muffins and jam, and codfish tongues in black butter. They knew that the day ahead of them would be long and difficult - although they did not imagine just how difficult it was going to be.

Dr. May, a florid, cheerful gentleman in his sixties, was wearing the clothes he reserved for weddings, coaching parties, and New Years Day: a cutaway, a four-in-hand tie, and a waistcoat of plum-colored Chinese brocade. Mrs. May was in a peignoir, but waiting upstairs to be put on right after breakfast were her tightest corsets, and a Paris-made evening dress: sapphire-blue velvet trimmed with yards and yards of Valenciennes lace, dozens of blue silk roses, and seventy-five gilt tassels.

Four pretty May daughters were having breakfast on trays in their rooms so that they would be ready when a French coiffeur arrived at eight to curl their hair and twine it with velvet bands and swans-down. As soon as that was done, they would be engineered into corsets so that their twenty-three-inch waists would become eighteen-inch waists. Then they would put on billows of organdy and mousseline de soie in the seasons most fashionable colors: amber dust, pink coral dust, bears ear, and silver-willow.

Edith, the oldest, was engaged to a clashing English guards officer, while the two younger ones were not out yet and therefore not ready for the marriage market. Just now the family attention was focused anxiously on the second sister, Caroline, who was being courted by a man of new wealth. Dont marry for money, but marry where money is was a favorite precept of Victorian mothers. But the question here was, should one marry where money is but where good family background is not?

The Mays were a top-drawer family, originally from Boston, where a great-grandfather had been one of the merchants who had chucked British tea into Boston Harbor. Their branch had spread out to New York, Baltimore, and Washington and had left behind the plain living and high thinking of their Boston cousins. In New York, it seemed one had to have more and more of everything: clothes, jewels, carriages, servants, tickets to the opera, trips to Europe. Mrs. May often said wistfully that she could remember when the most exciting thing in a young girls life was a little supper-dance at home, with canvas put down over the carpet to dance on and favors of fresh nosegays and boutonnieres. Only people-we-know were invited, and there was no ostentation, But now, private dances were being given in public places, like the fashionable restaurant Delmonicos, and favors were likely to be real gold charms and stickpins.

Two years earlier - on the day after Christmas, 1874 - the annual Patriarchs Ball, the most exclusive party of the year, had been held at Delmonicos, and the guest list had included at least a dozen persons whom most of the others present had never met before. That occasion had come to be called The Bouncers Ball - bouncer being post-Civil War slang for a person who suddenly acquires a fortune.

Anxious parents asked themselves whether it was right for their daughters to be in the same ballroom with that sort. And the Mays were particularly concerned with the problem because their daughter Caroline, at another such unconventional ball, had met the rich and powerful outsider (some said bouncer) who was now paying her court.

Soon after eight oclock that morning, the Mays areaway doorbell began to ring. First came the hairdresser. Then florists boys arrived, delivering baskets of flowers for Mrs. May and bouquets for the girls. A caterer brought a many-tiered cake with spun-sugar swans on top. And a harried young dressmakers assistant turned up to be sure that Mrs. May fitted into her new dress.

At ten, the May ladies were in the front parlor, peering through the embroidered-net curtains to see which sleighs and carriages might be stopping at their door. Dr. May put on his seal-collared, wool-wadded greatcoat, a top hat, and chamois gloves and bade his family goodbye. He would be out all day, making forty or fifty calls and hoping to stay healthy, because there was always a lot of work for doctors after New Years Day, with its sudden chills and overheating and nonstop indulgence. Descending the stoop, he stepped into a hired sleigh. He had not wanted to subject his own horses to a day in the streets and had reserved this sleigh and driver several months before, even though the holiday price was $50.

The May brownstone had two large parlors, one behind the other, with a double door between. Wine-colored velvet draped the windows and the connecting door, and the carpet bloomed with dark-red cabbage roses. The woodwork was painted dark chocolate. There were a lot of gilt-framed mirrors, bronze and marble statuettes, and paintings, but Edith, Caroline, Julia, and Alice, very aware of what they saw in houses like the Astors or the Lorillards, thought there were not enough and pointed out a few empty spaces on the walls and on the marble tabletops. They were pleased, however, with the inlaid rosewood, plush-upholstered chairs and sofa recently purchased from Herter Brothers. Against this somber background, the May ladies fluttered about like bright birds.

On New Years Day in New York, front doors were left on the latch, for it was the custom - an old Dutch one - for guests to walk in without ringing. Sometimes unwanted gentlemen came in with the wanted, but (as Harpers Bazar had recently told its readers) the generous spirit of the day insures them tolerance, and there was seldom any unpleasantness. Ladies who did not wish to receive calls at all that day might affix a basket, for cards, to the doorknocker.

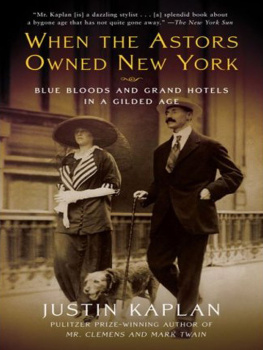

Soon after ten, the Mays first caller walked up the stoop, wearing a sealskin coat down to his ankles. Young Alice, peering through the filmy curtains, exclaimed, Oh, Mamma! Its Mr. Astor!

Mrs. May was pleased to receive Mr. William Astor but wished he had not come so early. That meant that he was saving his later calls for households he considered more important. The Mays were sure that they were more important than the Astors - at least, as far as ancestry went. Still, better an Astor making an early call than a Vanderbilt, whose money (people said) was so recently acquired that when they walked by you could hear the new bills crackling.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties»

Look at similar books to Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Top Drawer: American High Society From the Gilded Age to the Roaring Twenties and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.