Contents

Guide

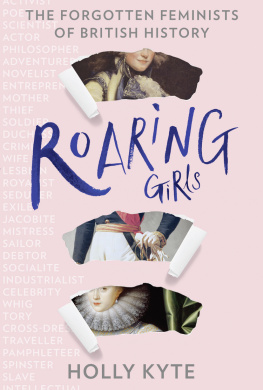

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Text copyright Holly Kyte 2019

Illustration copyright Becky Glass 2019

Cover images: Dorothy Jordan by John Hoppner, 1791 National Portrait Gallery Duke of Aumale by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1846 Bridgeman Images Lady Diana Cecil attrib. to William Larkin, c. 1614 Bridgeman Images

Holly Kyte asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008266080

Ebook Edition 2019 ISBN: 9780008266097

Version: 2019-11-21

For Mum and Dad, for everything.

roaring girl: (n) a noisy, bawdy or riotous woman or girl, especially one who takes on a masculine role

OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY

Spellings, capitalisation and italicisation have been silently modernised throughout for clarity and consistency.

Girls, were told, are not supposed to roar. Were supposed to shut up, be quiet, stop nagging. Were supposed to calm down, dear. If we dont, were bossy, were aggressive, were nasty, were bloody difficult. Were a bunch of loud-mouthed feminazis and hysterical drama queens. If our skirts are too short, were asking for it, but if we dont make an effort, we should be ashamed. If we dont speak out, how can we expect recognition? But if we do speak out, we get trolled. And thats in the twenty-first century, after four waves of feminism, when equality has supposedly been won.

Imagine, just for a moment, that youre a woman in the seventeenth century. In your world, feminism doesnt exist. Youve been born into a rights vacuum. Your life is one long list of obligations and prohibitions. Your sole destiny as a wife and mother has been preordained since day one and the feminine ideal expected of you is to be chaste, modest, obedient and, whenever possible, silent.

But what if you dont want to be silent? What if you want to roar?

Mary Frith was just such a woman. A notorious cross-dressing thief in Jacobean London, she was smashing up every rule in the book when she swaggered onto the stage of the Fortune Theatre in the spring of 1611, dressed in a doublet and a pair of hose, sword in one hand, clay pipe in the other, to perform the closing number of the play she had inspired. It was called The Roaring Girl.

A Roaring Girl was loud when she should be quiet, disruptive when she should be submissive, sexual when she should be pure, masculine when she should be feminine. She was everything a woman was not supposed to be, and in a world before feminism, she was societys worst nightmare.

A WOMANS LOT

The eight Roaring Girls who feature in this book lived in Britain in the 300 years before the first wave of feminists fought tooth and nail for womens suffrage in the late 1800s, and during those centuries, the political and cultural landscape of the country changed almost beyond recognition. Collectively, these women witnessed the final wave of the English Renaissance and the last days of the Tudors. They saw their country rent by Civil War, their monarch murdered and his son restored. They found Enlightenment with the Georgian kings and experienced Empire and industrialisation in the long reign of Victoria. Britain was transforming at an astonishing rate, yet throughout this period though it was bookended by female rule a womans legal and cultural status remained virtually stagnant. She began and ended it almost as helpless as a child.

The sweeping systemic changes needed to revolutionise a womans rights and opportunities may have failed to materialise by the late nineteenth century, but the first rumblings of discontent had long been audible in the background. By the dawn of the seventeenth century, a radical social shift had begun to creak into action that would falteringly gather pace over the next 300 years. For although Mary Frith was the original Roaring Girl, she wasnt the only woman of the era to find herself living in a world that didnt suit her, and who couldnt resist the urge to stick two fingers up at society in response; the seeds of female insurrection were beginning to germinate across Britain, and the women in this book all played their part in the rebellion.

From the privileged vantage point of the twenty-first century, its easy to forget just how heavily the odds were stacked against women in Britain in the centuries before the womens rights movement, and how necessary their rebellion was. From the day she was born, a girl was automatically considered of less value than her male peers, and throughout her life she would be infantilised and objectified accordingly. Her function in the world would forever be determined by her relationship to men first her father, then her husband, or, in their absence, her nearest male relation. On them she was legally and financially dependent, and should she end up with no male protector at all, she would find it a desperate struggle to survive.

By the age of seven a girl could be betrothed; at 12 she could be legally married. Her only presumed trajectory was to pass from maid to wife to mother and, if she was lucky, grandmother and widow. Any woman who tried to deviate from this path would quickly find her progress blocked by the towering patriarchal infrastructures in her way. Denied a formal education and barred from the universities, she would find that almost every respectable career was closed to her. She couldnt vote, hold public office or join the armed forces. The common consensus was that her opinions were of no value and her understanding poor, and consequently she was excluded from all forms of public and intellectual life from scholarship to Parliament to the press. While the men around her were free (if they could afford it) to stride out into the world and participate in all it had to offer, she was expected to know her place and to stay in it suffocating in the home if she was genteel; toiling in fields, factories, homes and shops if she wasnt. Genius was a male quality, and leadership a male occupation. Even queens would have their qualifications questioned by men who assumed they knew better.

The only careers open to a woman during this period were those of wife and mother, but even if her homelife turned out, by chance, to be happy, these roles still came with considerable downsides. Legal impotence was perhaps the most obvious. In the eyes of the law, the day they married, a husband and wife became one person and that person was the husband. From that moment on, the wifes legal identity was subsumed by his.