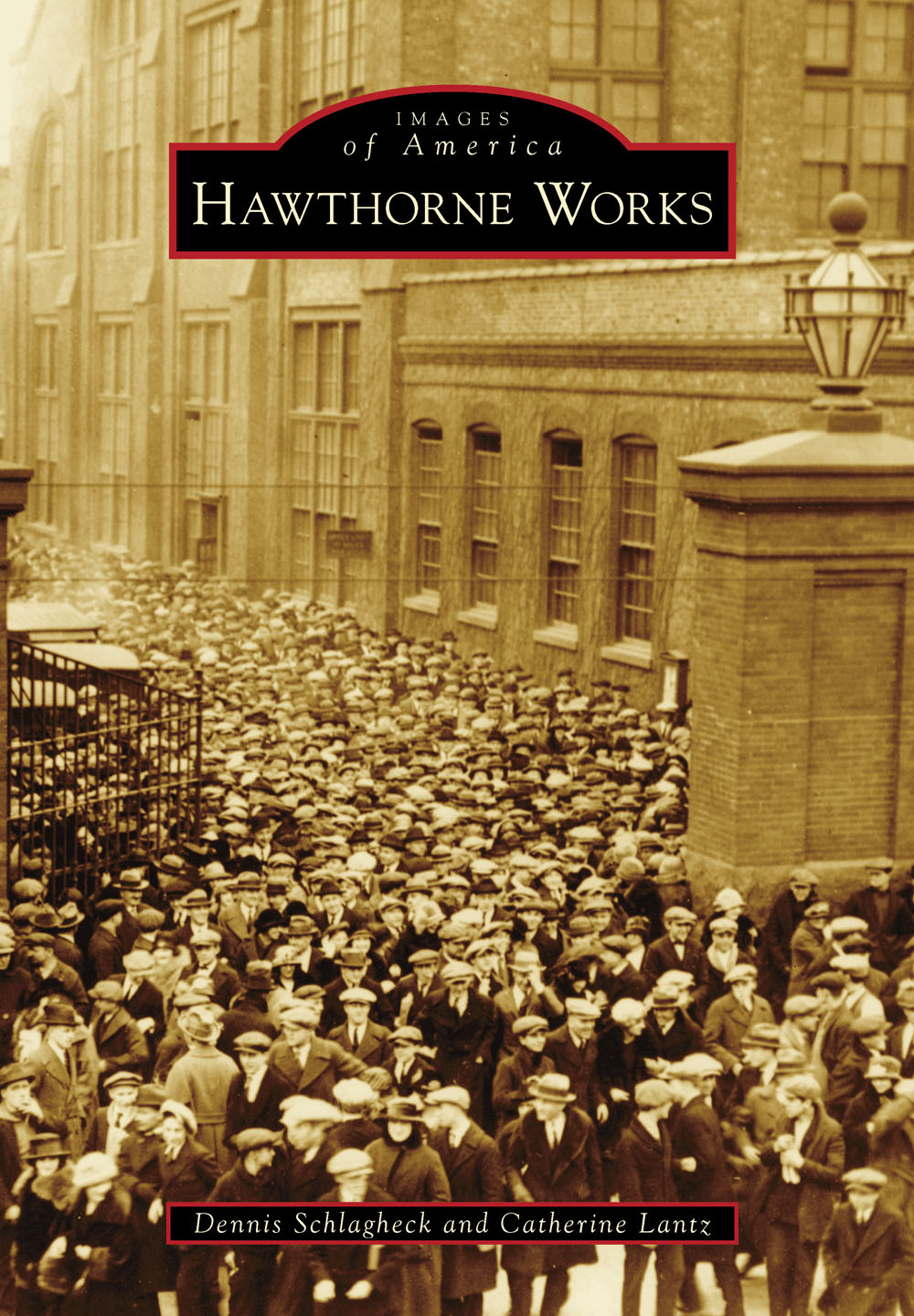

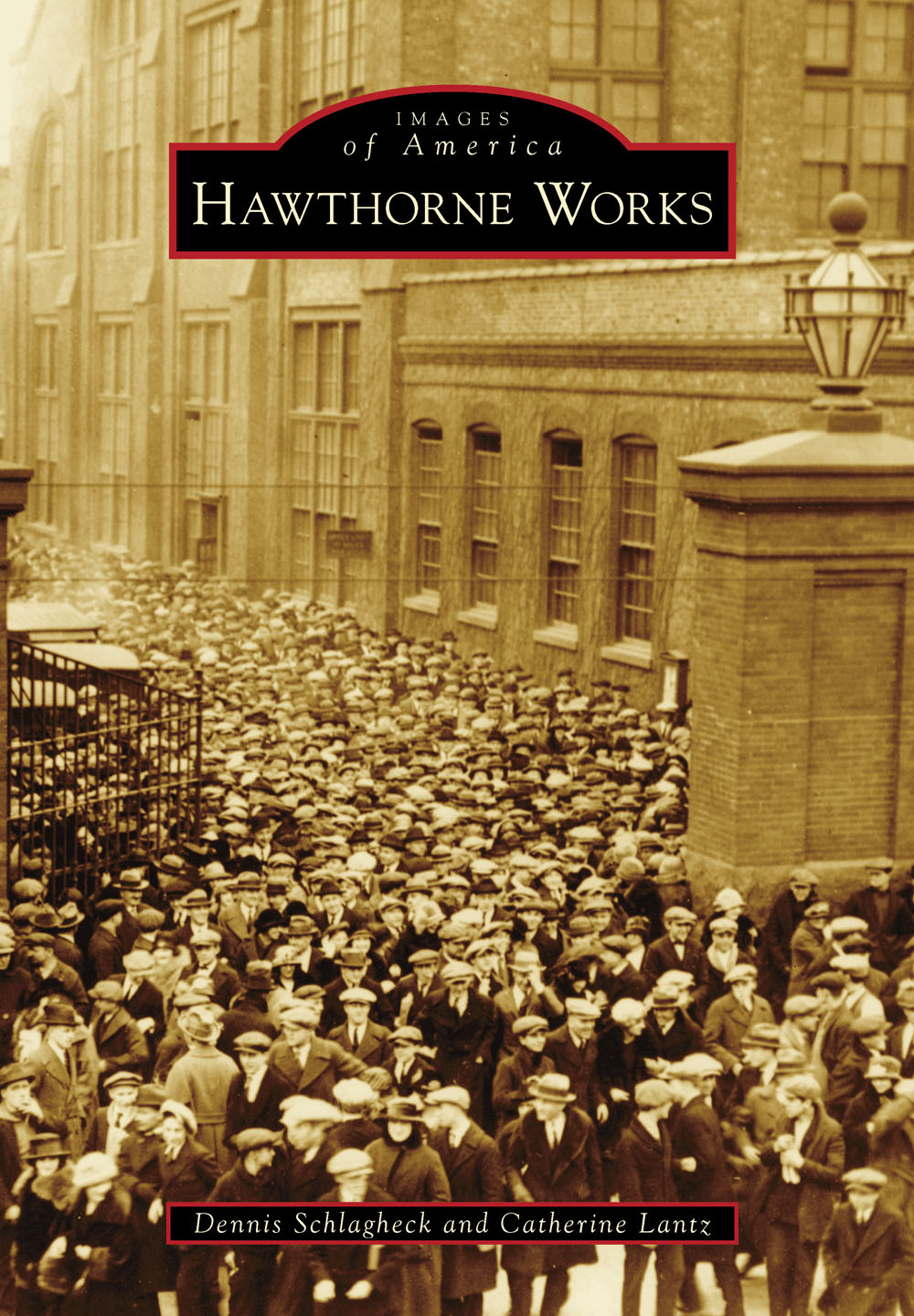

IMAGES

of America

HAWTHORNE WORKS

For more information about Hawthorne Works, visit the Hawthorne Works Museum, located on the Morton College campus, at 3801 South Central Avenue in Cicero. (Courtesy of the Hawthorne Works Museum.)

ON THE COVER: It is quitting time in the spring of 1924 as crowds of Hawthorne employees leave through Entrance No. 1, along Cicero Avenue. (Courtesy of AT&T Archives.)

IMAGES

of America

HAWTHORNE WORKS

Dennis Schlagheck and Catherine Lantz

Copyright 2014 by Dennis Schlagheck and Catherine Lantz

ISBN 978-1-4671-1135-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439644812

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013943909

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Tess and Emily: your smiles inspire me, your love uplifts me; to my sister Luisa: ikaw ang aking bayani!

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our thanks to the many people who said yes to us during every step of this projectyes to our requests for time, stories, images, and input. This book would not have been possible without their enthusiasm and support. We really appreciate the patience and talents of our Morton Library colleagues. A special thank-you goes to Jennifer Butler, the director of Morton College Library and Hawthorne Works Museum, for allowing us to take on this project.

The Hawthorne Works veterans, living witnesses to that special, long-lost time and place, added deeply personal touches and vivid details to our story. Our thanks go to Tom Brandsness, a Hawthorne employee from 1965 to 1985, for his devotion to preserving the memory of the Works and for sharing its positive influence on his life. We are also grateful to John Diaz, a Hawthorne Works fireman and security officer and the creator of the website www.westernelectric.weebly.com. John shared the Countdown tribute, a perfect and touching epitaph for the old Works. Tom Bell shared his memories of the cable plant. Many thanks for explaining the process so even we could understand it.

During our research, few things moved us as deeply as our discovery of the story of Virginia Ginny Brouk Davis. The real lives lived at Hawthorne need no embellishment, by Hollywood or otherwise, and we are honored that she has allowed us to tell another generation about her courage and resilience. Our gratitude also goes out to genealogist Jennifer Holik, the author of To Soar With the Tigers, for connecting us with Ginny and for providing generous advice and encouragement.

Marian Manseau Cheatham, the author of the novel Merely Dee, set in the era of the Eastland tragedy, offered honest and professional critiques to a novice writer. Thank you for your helpful suggestions and uplifting support.

George Kupczak of the AT&T Archives and History Center in Warren, New Jersey, lent his time, talent, and resources to the project. His guidance and hospitality are greatly appreciated. The archives website, techchannel.att.com, is a priceless treasury of the history of telecommunications.

Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the Hawthorne Works Museum.

INTRODUCTION

About six miles southwest of downtown Chicago, there is a shopping center at the corner of Cicero Avenue and Cermak Road. Its only unusual feature is a five-story stone tower just behind the storefronts. With its decorative brick arches, slit windows, corner turrets, and steeple, the tower looks like it would be more at home in a medieval fortress or a Disney theme park. Few realize they are looking at the last vestige of an American historical landmark. These 200-plus acres were the home of the Hawthorne Works, a vast industrial complex of over 100 buildings with five million square feet of workspace. Known as the Electrical Capital of America, it was where the Western Electric Company kept pace with the nations demand for communications equipment. At its peak, over 40,000 workers passed through its gates each day. When Pittsburgh and Gary meant steel and Detroit reigned as the Motor City, the Hawthorne Works in Cicero stood for telephones. In its heyday, the Western Electric brand and the Hawthorne Works name were synonymous with cutting-edge telecommunications. The Hawthorne Works is worth remembering because it was more than just another factory. Its story is nothing less than the story of the rise and fall of urban industrial America in the 20th century.

When Hawthorne opened in 1905, its shops were filled by immigrant workers struggling to secure a place in a strange new homeland. The Hawthorne Works exerted a powerful influence over their lives. With its own hospital, railroad, power plant, athletic fields, fire department, and night school, the Works functioned as a modern industrial commonwealth. Its workforce bought homes with loans arranged through the employee-run club, joined company-sponsored sports teams, drove automobiles on paid vacations, and planned for retirement on a company pension. Instead of squalid housing or company-owned towns, solid working-class communities sprang up. Hawthorne employees worked together, played together, lived together, and, at times, tragically, died together.

Year after year, Hawthornes workers turned out an endless stream of complex communications apparatus, engineered by the sharpest minds in the field and assembled by skilled craftsmen. The companys accomplishments won the admiration of business leaders around the globe and inspired pioneering research in industrial psychology and labor relations. The Works bustling shops provided the perfect setting for testing new manufacturing methods, and company officials gladly served up employees as subjects for groundbreaking studies whose results are still debated by psychologists and sociologists.

In its time, the Hawthorne Works exemplified the virtuous circle: a win-win proposition whereby corporate success forged a bond of loyalty with its employees. Today, when cradle-to-grave care is often scorned as a soft-hearted and soft-headed business model, when labor struggles to be heard and management looks only to downsize and outsource, Hawthornes decades of prosperity stand as a model of a workable middle ground, somewhere between class antagonism and plutocracy. This carefully crafted partnership left a permanent imprint on American society.

Curiously, Americas privately owned telephone system, a showpiece of free enterprise, owed much of its success to the government-sanctioned monopoly of the nations telephone service for much of the 20th century. The Bell Systems vertical configurationlong distance (AT&T), research (Bell Labs), manufacturing and supply (Western Electric), and service (regional Bell companies)assured its dominance. But as the technological landscape changed, newcomers clamored for a piece of the telecommunications pie and drew the Bell System into the swirl of downsizing and breakups that characterized American business in the last decades of the 20th century.

As the century closed, the heavy industries that fed generations of Americans and built a bridge to the middle class disappeared with alarming speed, the Works along with them. Hawthornes very size, which allowed it to function on such a vast scale, became impractical. Tasks were dispersed to other plants, the payroll shrank, and the imposing red brick edifice looked like a relic of a past age. But the end came not because its employees became complacent or less efficient, not because its engineers ran out of ideas, but simply because its time had passed. The very technologies its workers had done so much to make a part of everyday life rendered it obsolete.

Next page