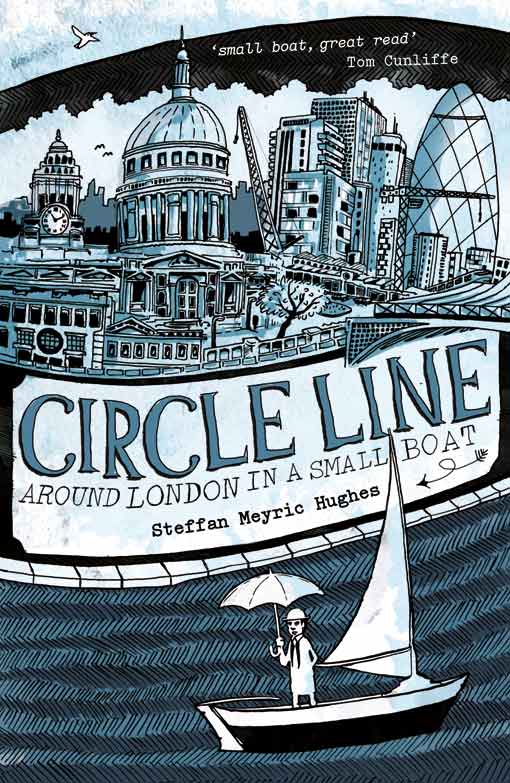

CIRCLE LINE

Copyright Steffan Meyric Hughes, 2012

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

The right of Steffan Meyric Hughes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-0-85765-765-7

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details telephone Summersdale Publishers on (+44-1243-771107), fax (+44-1243-786300) or email ().

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Steffan Meyric Hughes is a canoeist and sailor trapped in the body of a journalist. He has written for TheObserver, The Independent, Time Out and various marine titles. He is currently news editor at the monthly yachting magazine Classic Boat and lives in Finsbury Park, north London. This is his first book.

For Lara

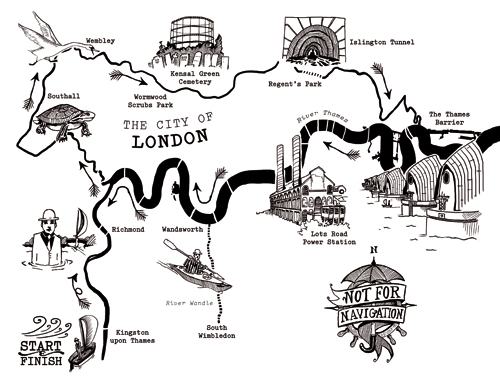

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

DAYS OF POWER, 1990

Chapter 2

OF DOWNSHIFTERS, KINGS AND SPEED FREAKS

Chapter 3

SAIL WHEN YOU CAN

Chapter 4

DEAD WATERS

Chapter 5

STANDARD LIFE

Chapter 6 S

HIT CREEK

Chapter 7

FORCED TO CAMP

Chapter 8

DRAGONS AND TRAFFIC CONES

Chapter 9

ANGRY SWANS AND SAILING OVER A-ROADS

Chapter 10

DREAMS OF LEAVING

Chapter 11

ABOUT THE UMBRELLA

Chapter 12

THE STEAMING SPIRES OF COMMERCE

Chapter 13

THE REAL CIRCLE LINE

Chapter 14

DOWN THE INTESTINE

Chapter 15

WAITING FOR THE TIDE

Chapter 16

THE SMALL, METALLIC TRAIN RIDE

Chapter 17

SAILING ON SKIN

Chapter 18

BURIED ALIVE

Chapter 19

DOWNTOWN

Chapter 20

A TALE OF TWO SHIPS

Chapter 21

THE RULES

Chapter 22

TRAMPING

CHAPTER 1

DAYS OF POWER, 1990

London: The train over the river, the 'power station wave' and a novel idea.

Every man must believe in something. I believe I'll go canoeing.

H. D. T HOREAU

I t was only at low water, and better still a spring low, when the sun and moon combine to try to suck the water off the face of the earth, that you'd see the 'power station wave'. When the Thames ran out to sea leaving half the riverbed bare, you would see the cooling outlets of the Lots Road power station playing into its industrial little creek that resembled well, to my mind anyway a cataract of the White Nile. The power station, behind its faade of old London brick, hummed as it generated 92 megawatts of electricity rushing quietly through pythonous cables to power the tube trains running beneath the city.

Every time it was low tide, we'd get into our battered, blue, riveted-aluminium powerboat and skim west over the Thames from our canoeing club in Pimlico, our heads completely and magnificently filled with the fractured whine of the Tohatsu 40 hp two-stroker and the splashing of the hull on water. We'd arrive at the little creek in Chelsea, get into our plastic, dayglo kayaks, balance on the rim of the powerboat, snap neoprene spraydecks onto the edge of our cockpits and drop like seals into the river. Even from a distance, we'd hear the smooth, high pitched whine of the Rolls-Royce turbines, like a fleet of muted 747s taking off, and the sound would fill me with a sick, nervy excitement I can still feel every time I'm at an airport even at the most mundane moments of modern travel, like buying expensive post-9/11 toothpaste after losing mine at check-in.

On the cooling outlet wave, we would, over the space of a few years, learn the elemental craft of paddling a kayak on white water. As fifteen-year-old kids, it passed us by that some of the things we were learning were as old as civilisation. We were gear freaks, more interested in the next new paddle, new boat or new crash helmet, than in the reality of what we were doing. We should have guessed by the names. The Eskimo roll, clearly as old as the Eskimos who invented it; the ferry glide, crossing a stream with bows pointed upriver to compensate for the flow, sounds as though it may have been used by the ferryman of the River Styx. It took years for us to overcome our fear of drowning and just hang there upside down in the murk, before flipping upright again with a stroke of the paddle. Sometimes, after what felt like a near drowning on a cold February day, I would wonder why we did it. If we'd had more success with girls, no doubt we wouldn't have. Sometimes, on a sunny day, I'd cup a bit of the river in my hand and see tiny particles of warm brown river sediment floating in the water. I used to think the Thames was my river I still do, even though I now know others have a greater claim.

If I wasn't on the river, I was by it. School was on the river, and I'd see it going to school, returning home from school, and out of the window I'd gaze at it all day long. Often I'd stop by Blackfriars Bridge on a fast spring tide and see the power of the brown water funnelling through the spans of the bridge, setting up trains of standing waves that bounced off the immovable, grey stone support stanchions in big dirty pressure cushions. Standing waves are just like waves at sea, but with one big difference: at sea, the water stays in the same place and the wave energy moves through it; on a river, the energy stays in the same place and the water moves through it. I couldn't look at a body of water without wanting to be on it or in it and, at nights, I'd dream of the river.

In 2002, Lots Road Power Station, like Battersea and the others before it, shut its turbines down and the wave fell flat. It was the last working example of London's cathedrals of power, the grand, brick buildings of the Edwardian era when inventors like Thomas Edison were kings and progress was the future. Lots Road was built in the early 1900s to convert the steam-driven underground trains to the new, cleaner power of electricity. It was the biggest power station in the world when it went up, and the first building in London to top the dome of St Paul's Cathedral. When it stopped generating, it seemed like the end of London's days of power and the beginning of its new incarnation as a centre for commerce and theme park commemorating its own past, a history of relics that were all the next big thing and it seems unbelievable to me that a bunch of kids for a period of about five years were allowed to use the cooling outlet pipes of a power station as our playground, taking heavy-metal industrial technology for a joyride.