About the Authors:

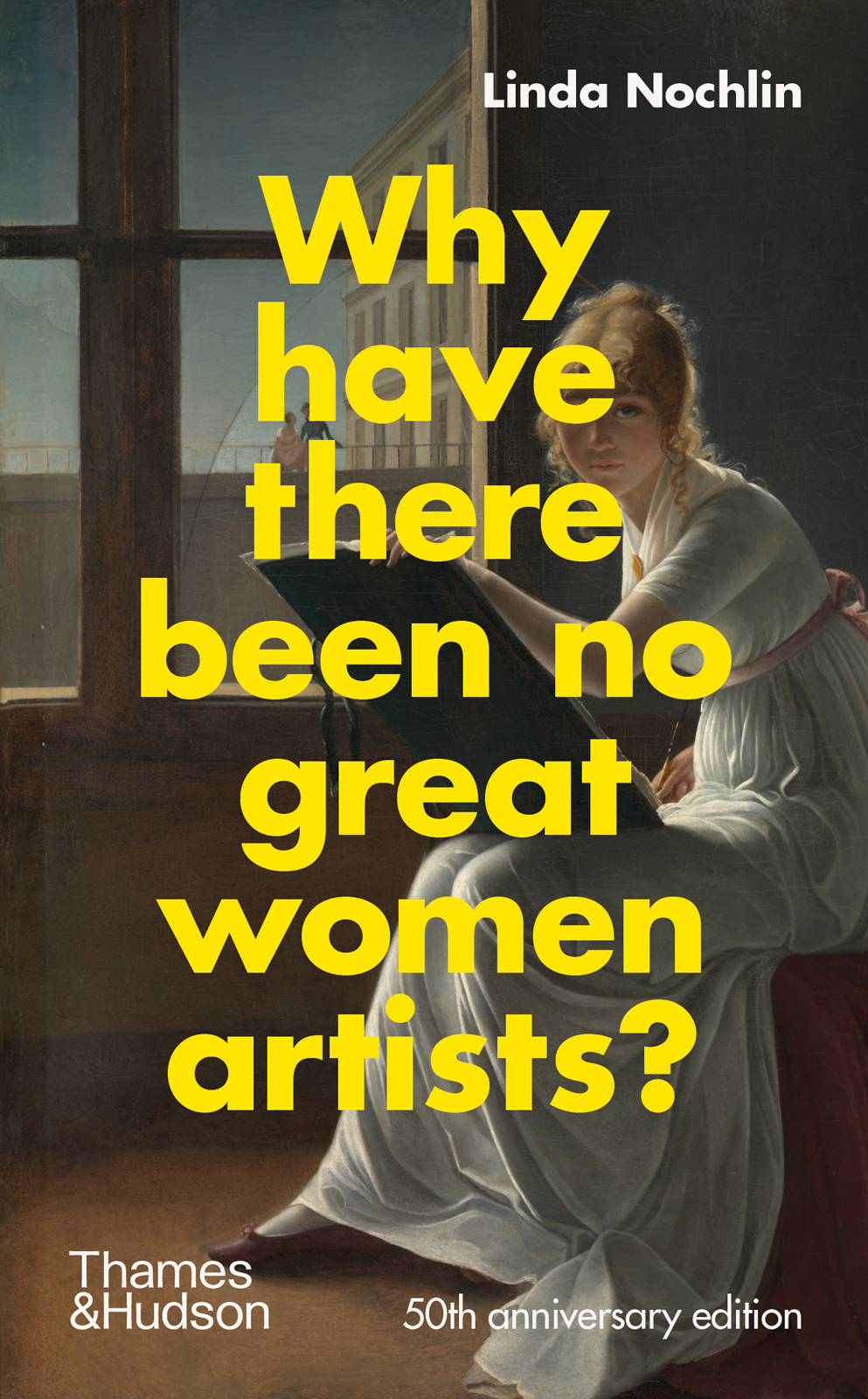

Linda Nochlin (19312017) was Lila Acheson Wallace Professor Emerita of Modern Art at the New York University Institute of Fine Arts. She wrote extensively on issues of gender in art history and on nineteenth-century Realism. Her numerous publications include Women, Art and Power, Representing Women, Courbet, Women Artists and Misre.

Catherine Grant is Senior Lecturer in the Art and Visual Cultures Departments at Goldsmiths, University of London. She has published extensively on feminist histories in contemporary art, and is the co-editor of Girls! Girls! Girls!, Creative Writing and Art History and Fandom as Methodology.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Misre: The Visual Representation of Misery in the 19th Century

Linda Nochlin

Representing Women

Linda Nochlin

Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader

Linda Nochlin

Be the first to know about our new releases, exclusive content and author events by visiting

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

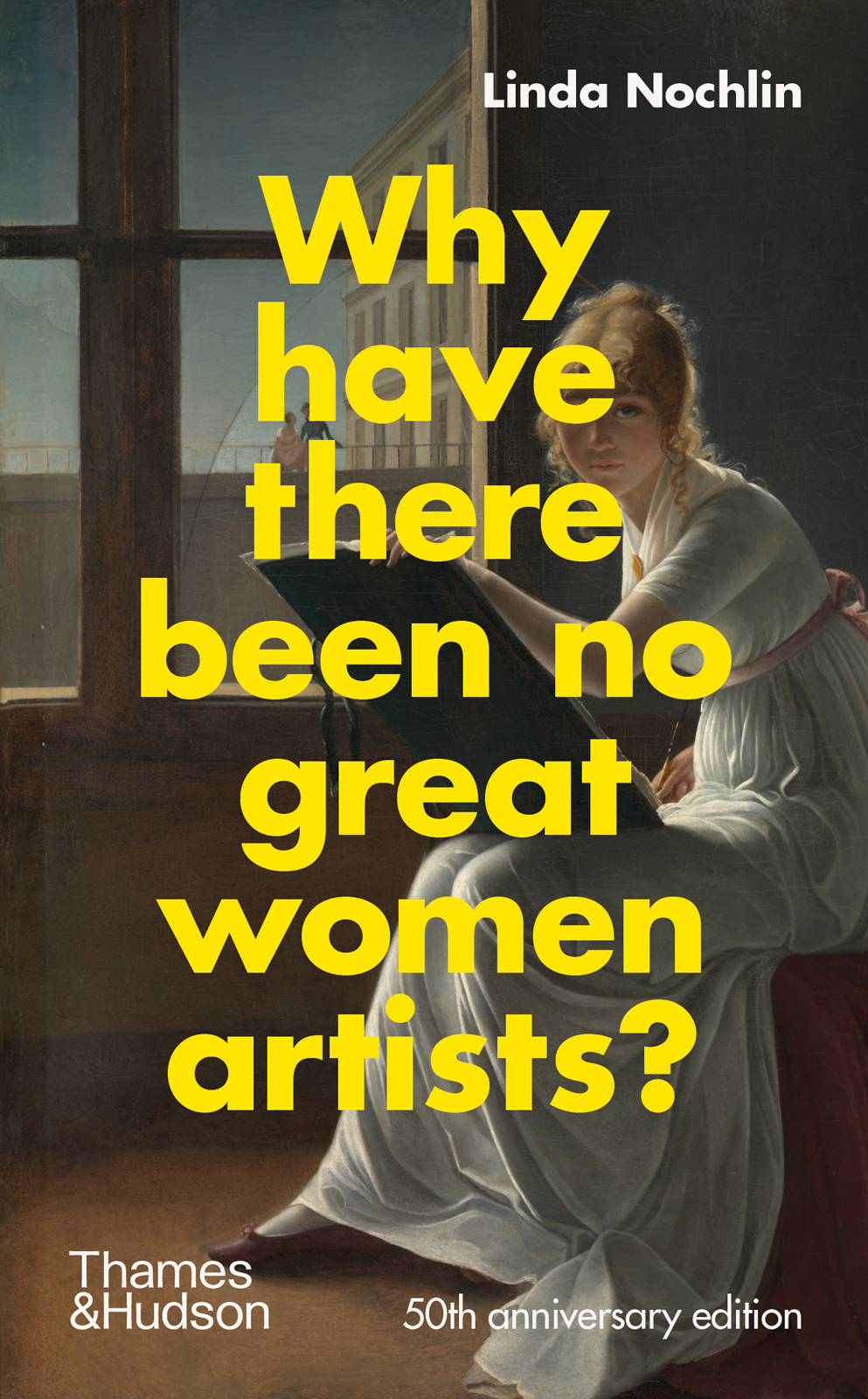

Contents

Linda Nochlins essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, first published in 1971, established the ground for feminist art history. It remains relevant today for its vivid critique of greatness as an innate quality, as well as for exploring how women artists have managed to succeed against institutional exclusion and social inequalities. As a number of commentators have explored, the term woman artist is as much of a historical construction as that of the great artist. Her conclusions and suggested lines of further enquiry remain open for further investigation today.

In the fifty years since its publication, Nochlins essay has become a touchstone for feminist writers, artists and curators. Many undergraduate courses in art and art history continue to set it as an entry point into discussions around structural inequality and the fantasies that still abound when thinking about creativity and greatness. The title Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? has permeated popular culture to the extent that it was emblazoned on T-shirts at a Dior fashion show in 2017, with beautifully bound copies of the essay distributed to the spectators. With many women artists now considered great, is it still necessary to engage with Nochlins essay in detail? In this introduction, I will argue Nochlins critical analysis exposes assumptions that are still hard to shake within art and art history. I will summarize her essays key points, and contextualize them in relation to Nochlins own opinion of this foundational work, drawing on the second essay published here, written in 2001, and ending with a consideration of what is needed for feminist art history today.

One of the key elements of Nochlins 1971 essay is how she responds to the question Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? In the original version, published in the journal ARTnews as part of a special issue on Womens Liberation, Woman Artists and Art History, an introductory line reads Implications of the Womens Lib movement for art history and for the contemporary art scene or, silly questions deserve long answers. For women, then, she sets out (in one of the most quoted sections of the essay):

The fault lies not in the stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs, and signals.

After demolishing the fuzzy ground underpinning notions of greatness (including a detailed exploration of how women were excluded from a foundational skill for artists from the Renaissance to the end of the nineteenth century: drawing from nude models), Nochlin moves on to explore how women artists have succeeded. Using the nineteenth-century painter Rosa Bonheur as a case study, she describes how Bonheurs father was a impoverished drawing master, and that like many men (Nochlin cites Picasso), having an artist-father allowed for the blossoming of creativity that might later be attributed to a mysterious notion of genius. What she doesnt explore in detail is the presence of Rosa Bonheurs partner, the artist Nathalie Micas. Nochlin asserts that their relationship was most likely platonic, whereas now it is generally accepted that the two women lived as a married couple. Here Bonheur has an artist-wife or an artist-sister as well as an artist-father, pointing to a proto-queer-feminist community of at least two. By describing Bonheurs life, masculine dress, and relationships, Nochlin indirectly points to the subsequent emergence of lesbian and queer feminist thinking around communities, sexuality and non-normative kinship structures that continues into the present, as well as her insight that individual mens support, particularly that of artist-fathers, has been crucial in the face of patriarchal exclusions.

In discussing successful women artists such as Bonheur, Nochlin concedes that they may not have been art superstars on the level with Michelangelo or Picasso, but nonetheless, carved out spaces for themselves across the centuries, ranging from the thirteenth-century sculptor Sabina von Steinbach through to twentieth-century artists including Kthe Kollwitz and Barbara Hepworth. In her later writing, and in subsequent critiques of her work, this notion of masculine, Western superstardom is itself qualified as specific to the post-World War Two period. Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollocks important volume Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, from 1981, further argues that women artists were present in writing and exhibitions until the twentieth century, when they were erased from histories of art from the rise of modernism onwards. As Pollock puts it, feminist art historians in the 1970s had to become archaeologists to undo the structural sexism in the discipline of Art History itself.

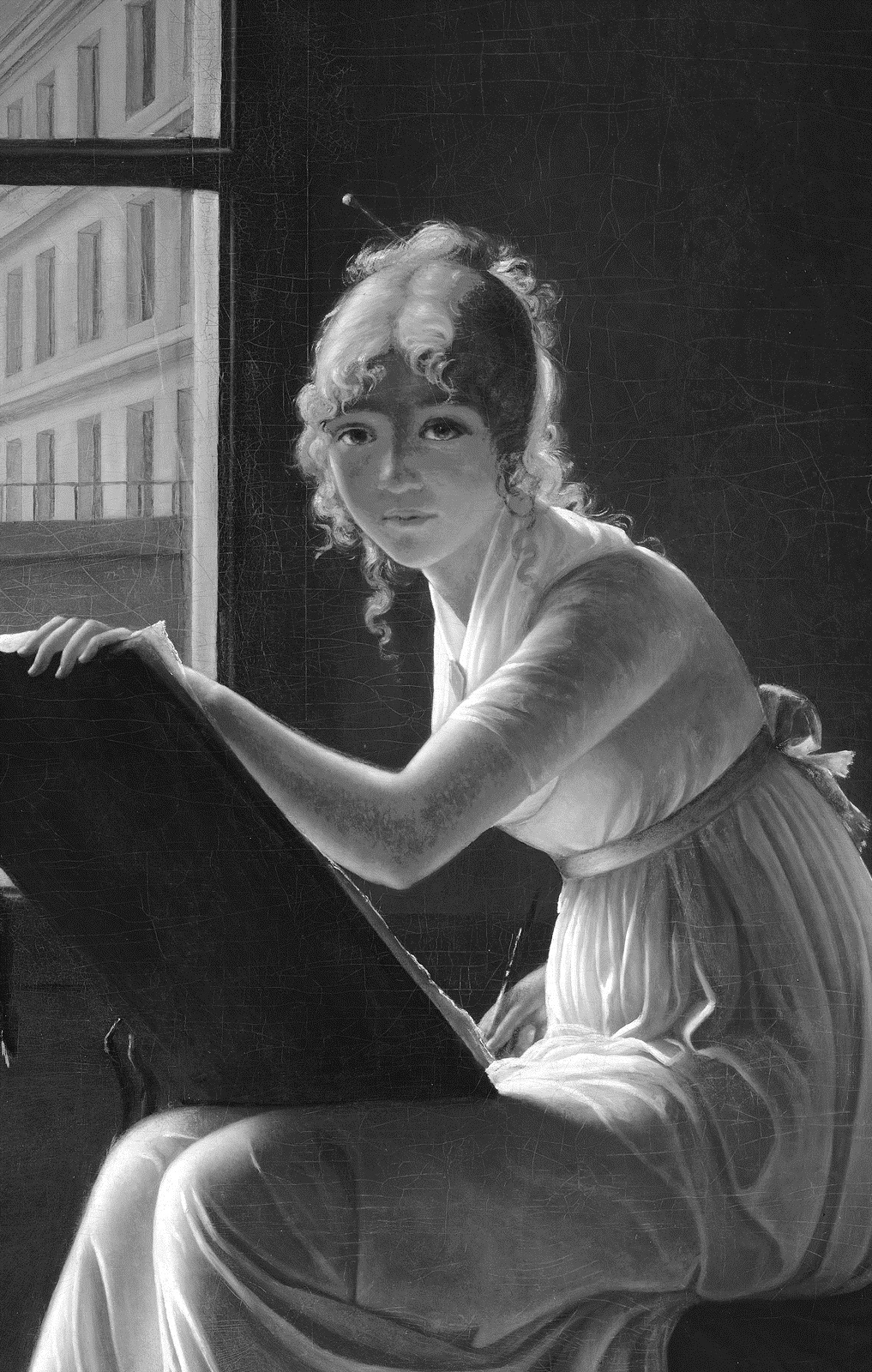

In Nochlins subsequent writing, and through curation of shows starting with Women Artists: 15501950 (with Ann Sutherland Harris) in 1976, she contributed to the huge project of re-imagining histories of art that do not exclude or belittle the work of women artists. In the original publication of Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? there are numerous illustrations that run alongside the text, ranging from a nuns collaborative medieval illumination from the tenth century to contemporary works by Agnes Martin and Louise Bourgeois. A full-page reproduction of Artemisia Gentileschis Judith Beheading Holofernes (c.161420) is placed opposite the title page of the original magazine version of the essay, with the caption asserting that this painting could be [a] banner for Womens Lib. Whilst the captions are not explicitly attributed to Nochlin, they have the same conversational lightness that drives her profoundly serious argument. These illustrated artworks by women assert the richness of practices that have been excluded from histories of art, and claims their importance, whilst still holding on to the central argument that refutes the ideological basis for traditional art historical judgment. The complex interplay that Nochlin achieves in the essay is sometimes misunderstood as a call to create a canon of great women artists. This is not the case, but her essay does begin to provide her (women) readers with the tools to imagine what it means to be a successful artist or write about womens art.

Next page