Acknowledgments

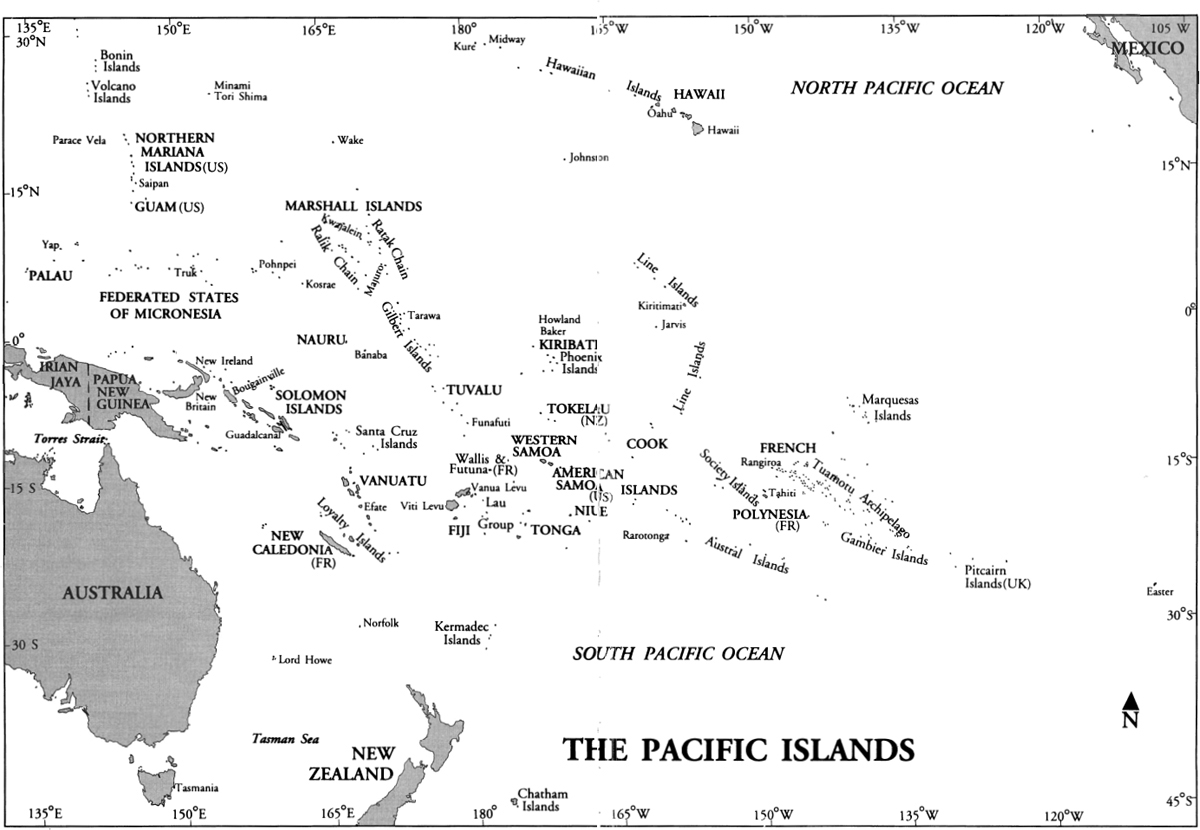

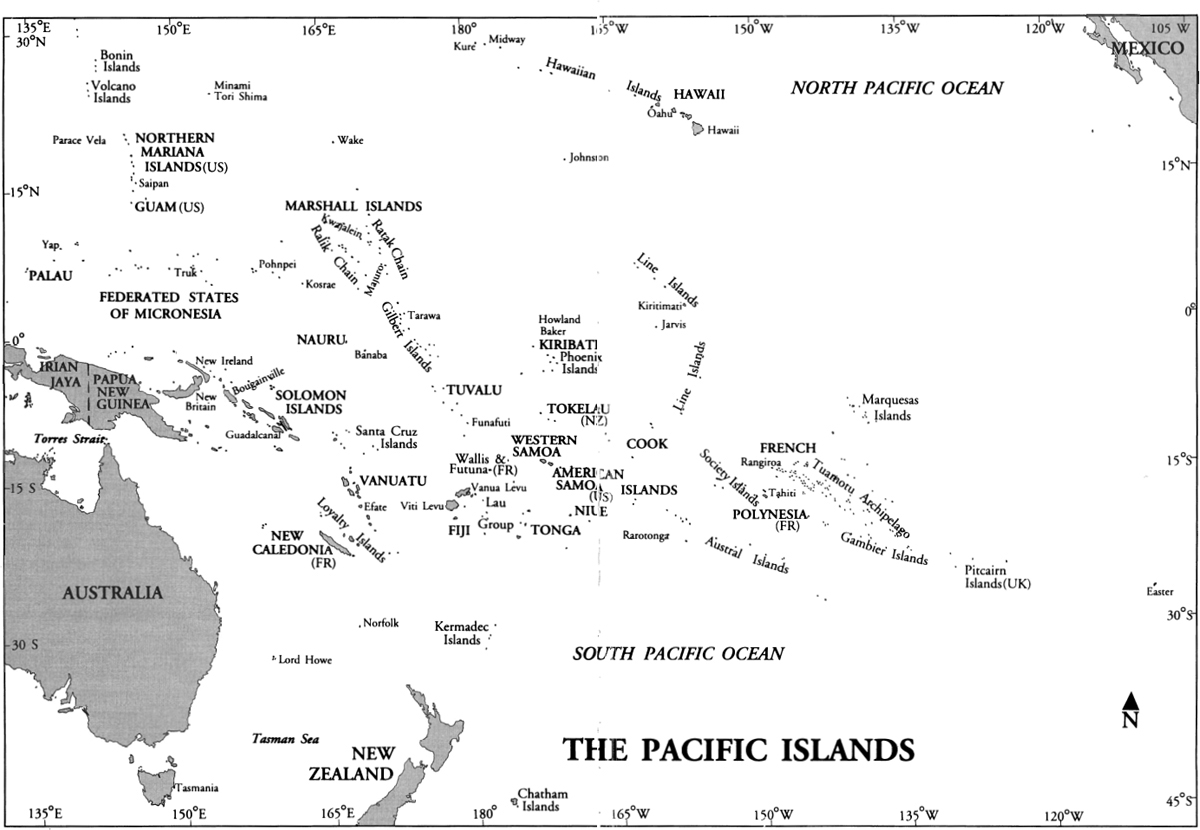

We gratefully acknowledge the help of the many Pacific Islanders who gave us generous advice, assistance, and hospitality. We particularly thank the farmers who furnished plant material and ethnobotanical information and the agencies and institutions that assisted field research, including the Department of Primary Industries of the government of Papua New Guinea; the Departments of Agriculture of the governments of the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga, Western and American Samoa, Wallis and Futuna, French Polynesia, and the Federated States of Micronesia; the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawai'i; and the Department of Geography at the University of Hawai'i.

Research and manuscript preparation were supported by the French Aid Program, the South Pacific Commission, the Office of Research at the University of Tulsa, the University of Hawai'i, and the U.S. Agency for International Development (Program for Science and Technology Cooperation grant 7.039).

1. Introduction

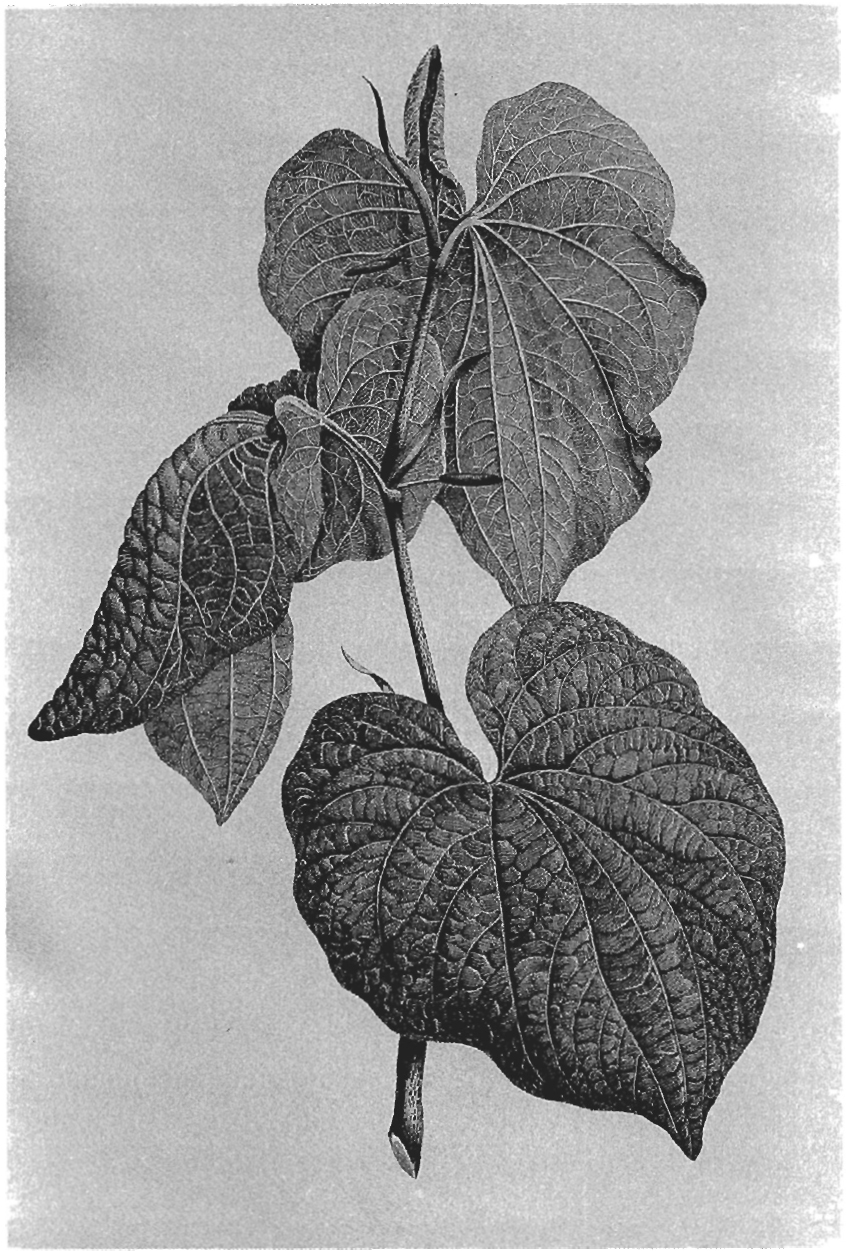

Kava (Piper methysticum Forst. f,), a member of the pepper family Piperaceae, is an outstanding ethnopharmacological species. The drug is, or once was, consumed in a wide range of Pacific Ocean societies, from coastal areas on the large Melanesian island of New Guinea in the west to isolated Polynesian Hawai'i, 7000 kilometers distant to the northeast. Kava is a handsome shrub that is propagated vegetatively, as are most of the Pacific's major traditional crops. Its active principles, a series of kavalactones, are concentrated in the rootstock and roots. Islanders ingest these psychoactive chemicals by drinking cold-water infusions of chewed, ground, pounded, or otherwise macerated kava stumps and roots.

One concern of this book is to pinpoint the place in the Pacific region where kava was first domesticated. Of the Pacific's two main traditional drug plants, kava is the indigenous species. The other, a palm (Aeca catechu), whose fruit is commonly called betel or betelnut, appears to have been domesticated in the vicinity of the Malay Peninsula and is used today throughout much of mainland and island Southeast Asia (Marshall 1987).

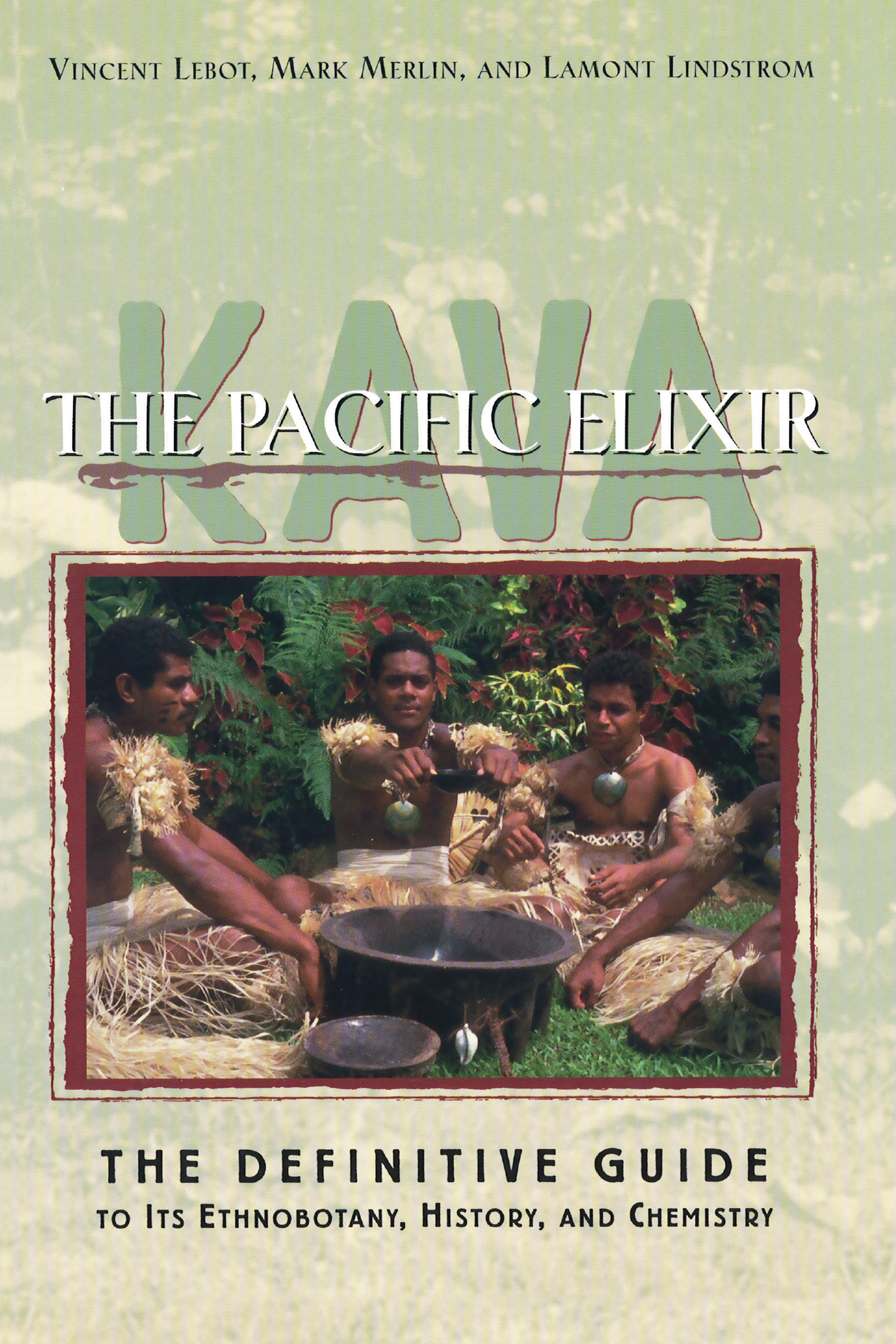

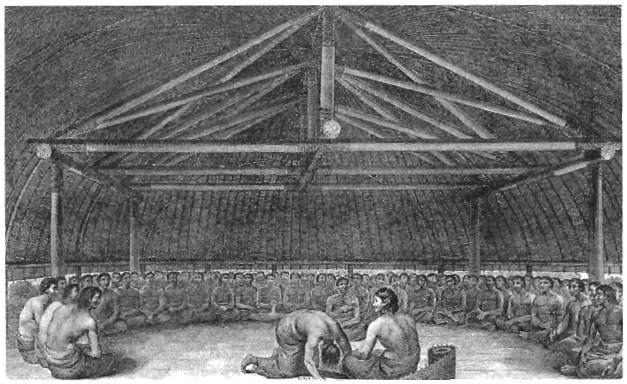

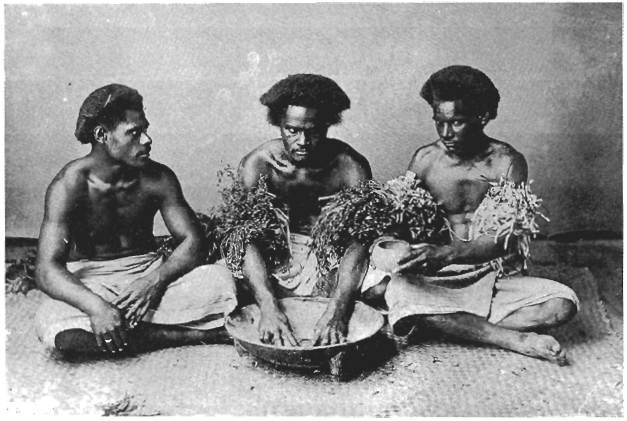

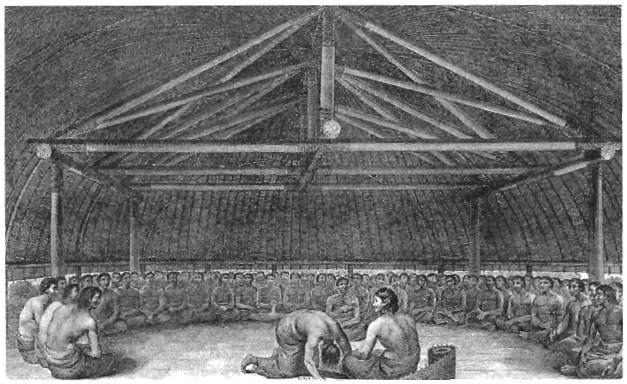

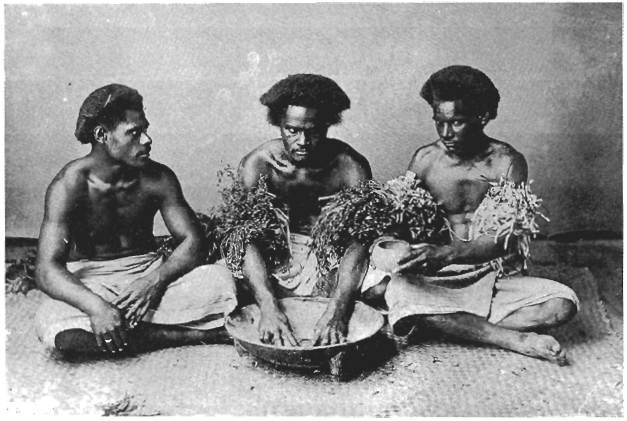

When European explorers first landed on remote Pacific islands, they encountered societies in which kava drinking was an integral part of religious, political, and economic life (figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3). Although cultivation and use of the plant has virtually disappeared from eastern Polynesia and Kosrae Island (previously Kusaie) in Micronesia, kava remains an important psychoactive drug in much of Melanesia, in most of the islands of western Polynesia (including Samoa and Tonga), and on Pohnpei Island in Micronesia (see appendix A).

Scientific observation of the use of kava dates to the earliest European voyages of exploration (figure 1.4). The eighteenth-century British explorer James Cook noted in his log that venturesome members of his crew who sampled heavy doses of the drug seemed to experience symptoms similar to those induced by opium. Cook's comparison was inaccurate, for kava is neither a hallucinogen nor a stupefacient. Rather, the drug is a mild narcotic, a soporific, a diuretic, and a major muscle relaxant.

Given the plant's complex and subtle psychoactivity, it is difficult to categorize in the terms of common drug classification schemes. Schultes and Hoffman (1979) follow Lewin (1924) and typify kava as both a narcotic and a hypnotic. Siegel (1989) describes the plant as a sedative hypnotic. The psychoactive potency of the drug can vary considerably, from very weak to quite strong. Kava may induce sociability, feelings of peace and harmony, and, in large doses, sleep, or it may fail to produce relaxation and provoke nausea. Typically, however, kava evokes an atmosphere of relaxation and easy sociability among drinkers. Although we use the terms intoxication, drunkenness, and inebriation to describe human physiological reaction to the plant, the state differs from that induced by ethanol or other familiar drugs found in the Western world.

Figure 1.1. "Poulaho, King of the Friendly Islands [Tonga) Drinking Kava," by J. Webber, artist on Captain James Cook's third voyage to the Pacific (courtesy of Hawaii State Archives, Honolulu).

Figure 1.2. Nineteenth-century studio photograph of kava preparation, Fiji (courtesy of the British Museum, Department of Ethnography).

Figure 1.3. Samoan taupou (ceremonial virgin) prepares kava (courtesy of Bishop Museum, Honolulu).

Kava has a strong but not unpleasant smell. Its taste, which can be acrid and astringent, has been characterized as earthy (or "like dirt" by less friendly drinkers). The botanist J. G. Forster (1777), who sailed with Cook on his first exploratory voyage, described kava infusions he sampled in Polynesia as either tasteless or mildly peppery. (We may assume that his sample was watered down; the flavor of kava is normally strong.) Like tobacco and coffee, kava for most people is an acquired taste.

The most reliable evidence suggests that cultivated kava derives from a wild progenitor, Piper wichmannii C. DC., a fertile Piper indigenous to New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu (previously the New Hebrides). Although many Western botanists distinguish P. wichmannii from P. methysticum, we argue that there now exist convincing morphological, chemical, and genetic grounds for considering these two taxa of Piper to be wild and cultivated forms of the same species. Piper methysticum consists of sterile cultivars cloned ultimately from P. wichmannii in an ongoing selection process. When we speak of kava, or the kava drink, therefore, we refer in the main to what botanists know as P. methysticum, although Pacific Islanders also cultivate and use as kava several varieties of the plant that botanists label P. wichmannii. We also use the word kava synonymously, as do Pacific Islanders, to refer to both the plant itself and the psychoactive beverage made from its rootstock.

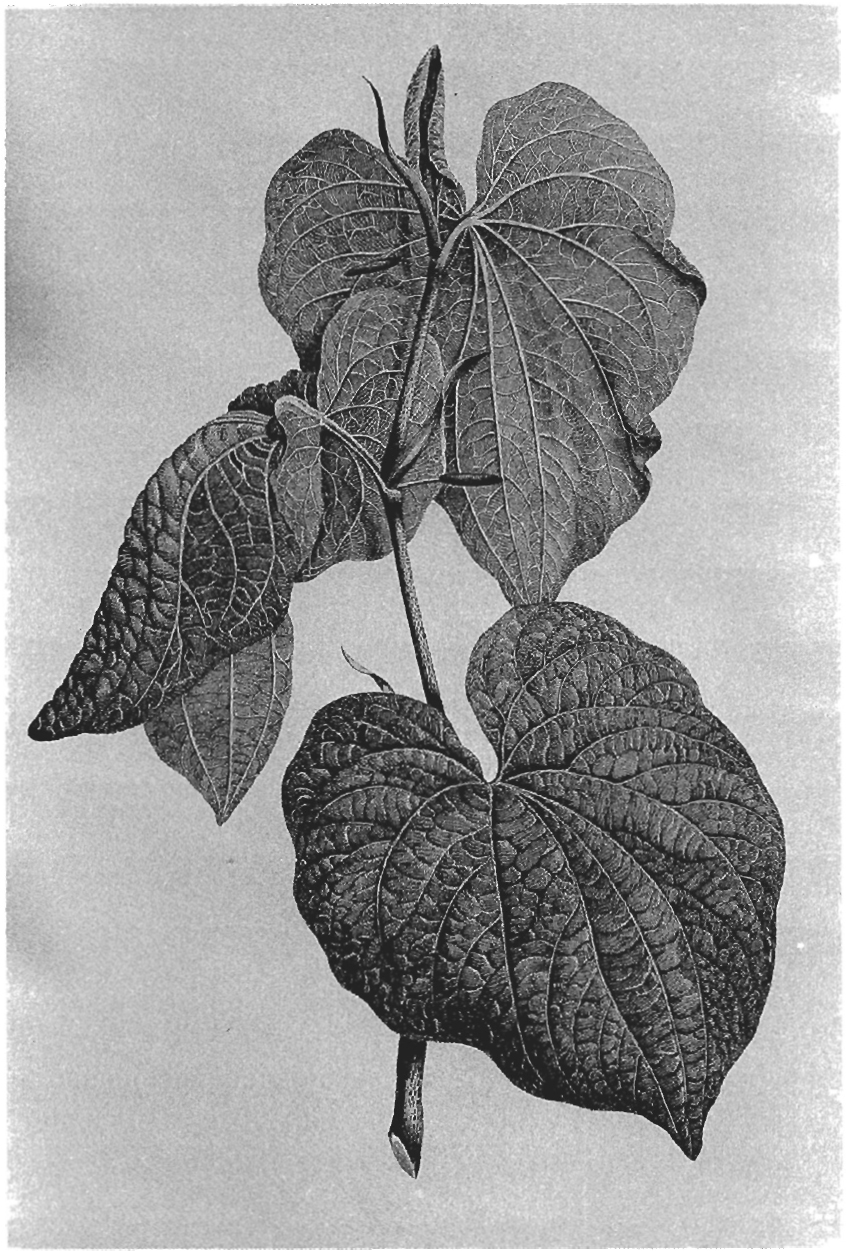

Figure 1.4.Piper methysticum, drawn in 1769 by Sydney Parkinson, the expeditionary artist on Captain James Cook's first voyage to the Pacific.

Today P. methysticum is a cultivated plant comprising many different cultivars grown widely throughout the insular tropical Pacific region. Each cultivar has specific requirements and a much more restricted range of distribution than P. methysticum as a whole. A remarkable variability in cultivar characters has developed over many generations of human selection of clones best adapted to the diverse local climates and soils.

Next page