This book was a pleasure to write, not just because of the many glorious days spent on the Boston Harbor Islands, but because of the people I met along the way. I can only hope that their passion for the islands comes across on these pages.

My particular thanks go to Union Park Press for originally publishing this book in 2008 and to Nicole Vecchiotti for her tireless work in producing the first two editions. Thanks also to Sarah Parke, who edited this new third edition, and to all of the staff at Globe Pequot Press for their interest in updating this Boston Harbor Islands guidebook.

Thank you to all who have shared their limitless knowledge, photographs, and, most important, love of the Boston Harbor Islands and to the librarians and archivists who assisted me in researching their history.

Enjoy your island adventures!

About the Author

Christopher Klein is the author of four books, including When the Irish Invaded Canada and Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan. A frequent contributor to History.com, the website of the History Channel, Christopher has also written for The Boston Globe, The New York Times, National Geographic Traveler, Harvard Magazine, Smithsonian.com, and AmericanHeritage.com. He lives in Andover, Massachusetts, and can be found online at christopherklein.com.

ALSO BY CHRISTOPHER KLEIN

When the Irish Invaded Canada: The Incredible True Story of the Civil War Veterans Who Fought for Irelands Freedom

Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, Americas First Sports Hero The Die-Hard Sports Fans Guide to Boston: A Spectators Handbook

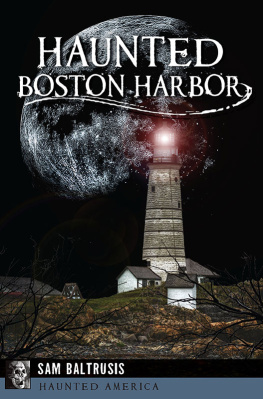

WITH ITS LABYRINTH OF DIMLY LIT PASSAGEWAYS, underground dungeons, spooky tunnels, and a drawbridge spanning a dry moat, mighty and historic Fort Warren on Georges Island is one of the most visited attractions on the harbor islands. Though it was active from the 1850s through World War II, Fort Warrens most notable role came when it served as a prison for Confederate soldiers and politicians during the Civil War. A visit to Fort Warren, now an important National Historic Landmark, promises a fascinating, hands-on lesson in history and a ghost story worthy of a good campfire.

Originally known as Pemberton Island (after James Pemberton of Hull, who owned and farmed the island in the seventeenth century), it was rechristened Georges Island by 1710. According to some accounts, the island took its new name from Boston merchant John George Jr., who may have owned land on the island and was likely the same merchant who petitioned the Massachusetts legislature to build Boston Light in 1713.

One of Georges Islands first military moments came during the Revolutionary War, when a large earthwork (a fortification made by altering the landscape) was built in 1778 on the eastern side of the island. At the time, the French fleet was anchored in the harbor for repairs, and the earthwork defended it against the British navy, which was still lurking about Boston Harbor even though they had evacuated the city on March 17, 1776.

The British may have lost America during the Revolutionary War, but thirty-odd years later they managed to successfully cripple Bostons commerce with a naval blockade during the War of 1812. As a result, the United States military decided to upgrade its fortifications along the Eastern seaboard, and the federal government acquired the island for coastal defense in 1825. Because of its strategic location at the throat of the Narrowsthe citys main shipping channel until the twentieth centuryGeorges Island was a natural choice as the site for the new fort.

Demilune on Fort Warren.

By 1825, however, heavy erosion and the sale of sand and gravel to passing ships in need of ballast had diminished Georges Island to half of its original size. The first act taken by the federal government after it purchased the island, therefore, was to build a massive seawall to protect it from further disappearing. By 1833, construction on the fort began in earnest. Fort Warrens ingenious (and very European) design was the brainchild of Sylvanus Thayer, an early superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy known as the Father of West Point. (Around Boston, he is also remembered as the founder of Thayer Academy in Braintree.) Though the fort was neither attacked nor ever required to fire its cannons, Thayers design, which incorporated impenetrable oak doors, portcullises, and a tremendous amount of armament, ensured it would have been ready. The fort was named in honor of Dr. Joseph Warren, a patriot hero who died in the Battle of Bunker Hillthough the name was actually transferred from an existing fort on Governors Island, which eventually vanished from the map when it was incorporated into Logan Airport.

It would take decades for teams of stonemasons, carpenters, blacksmiths, and other laborers to complete this massive construction project, which was constantly plagued by delays in appropriations and a lack of skilled labor (not an entirely unfamiliar saga to present-day Bostonians). When the military originally purchased Georges Island, it was composed of two drumlins, a topography similar to the East Head of Peddocks Island. Though the design of the fort took advantage of the islands landscape by incorporating the two hills into earthwork protection for the fort, some resculpting had to occur. Lowering and moving these hills in order to accommodate the fort was a considerable task, especially since the work was done by hand, using 536 picks and shovels and 406 wheelbarrows. Moving the granite blocks used to build the forts twelve-foot-thick foundation walls was no easy feat either. Quarried at Cape Ann and Quincy, the granite blocks were unloaded onto carts at the islands dock, pulled uphill by oxen, and lifted into place by large derricks. It took so long to build Fort Warren that by the time the Civil War began, the fort was still not fully functional, and its defensive design was considered virtually obsolete.

Union soldiers stationed at Fort Warren during the early days of the war are credited with composing the lyrics to the famous marching song John Browns Body, which was sung to a tune from an old Methodist revivalist hymn that began, Say, brothers, will you meet us? According to some accounts, the song may not have been originally composed to honor the real John Brown, the famed abolitionist leader who raided Harpers Ferry, but to poke fun at a soldier at Fort Warren who shared the same name. Regardless, the men of the Massachusetts Infantry who trained at Fort Warren carried the song with them into battle, and its popularity quickly spread through the Union ranks. The rhythm and memorable chorus of John Browns Body made it a natural marching song. When Julia Ward Howe heard Union troops singing the song while marching into battle, she was inspired to write an alternative set of lyrics. Those words, combined with the original melody, became an American anthem: The Battle Hymn of the Republic.

A little more than six months after the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, the federal government decided to transport Confederate prisoners to Fort Warren, which was under the command of Colonel Justin Dimick. The veteran officer was told to ready the fort for the arrival of 150 prisoners, so he was understandably shocked when, on Halloween in 1861, a boatload of more than eight hundred men docked at the island. Fort Warren was overrun and ill-prepared, which resulted in food rations and prisoners sleeping on floors. A newspaper account from November 1861 reported that when the prisoners arrived at Fort Warren pity rather than the hatred of the visitors was excited by the sad spectacle. Bostonians responded by donating food, beds, and other supplies to assist the Confederate prisoners, hoping that their proper treatment might inspire equal compassion toward Union prisoners of war. Additionally, these acts of generosity bolstered the moral high ground of abolitionists.