The Massey Lectures Series

The Massey Lectures are co-sponsored by CBC Radio, House of Anansi Press, and Massey College in the University of Toronto. The series was created in honour of the Right Honourable Vincent Massey, former Governor General of Canada, and was inaugurated in 1961 to provide a forum on radio where major contemporary thinkers could address important issues of our time.

This book comprises the 2019 Massey Lectures, Power Shift: The Longest Revolution, broadcast in November 2019 as part of CBC Radios Ideas series. The producer of the series was Philip Coulter; the executive producer was Greg Kelly.

Also by Sally Armstrong

Nonfiction

Ascent of Women: A New Age Is Dawning for Every Mothers Daughter (published in the U.S. as Uprising: A New Age Is Dawning for Every Mothers Daughter)

Veiled Threat: The Hidden Power of the Women of Afghanistan

Bitter Roots, Tender Shoots: The Uncertain Fate of Afghanistans Women

Fiction

The Nine Lives of Charlotte Taylor

Copyright 2019 Sally Armstrong and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

Published in Canada in 2019 and the USA in 2019 by House of Anansi Press Inc.

www.houseofanansi.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Power shift : the longest revolution / Sally Armstrong.

Names: Armstrong, Sally.

Series: Massey lectures series.

Description: Series statement: CBC Massey Lectures

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20189067829 | Canadiana (ebook) 20189067837 | ISBN 9781487006792 (softcover) | ISBN 9781487006808 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781487006815 (Kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: Sex discrimination against women. | LCSH: Sex discrimination. | LCSH: Womens rights. | LCSH: WomenLegal status, laws, etc. | LCSH: WomenSocial conditions. | LCSH: Women Economic conditions. | LCSH: Social justice. | LCSH: Human rights.

Classification: LCC HQ1236 .A76 2019 | DDC 305.42dc23

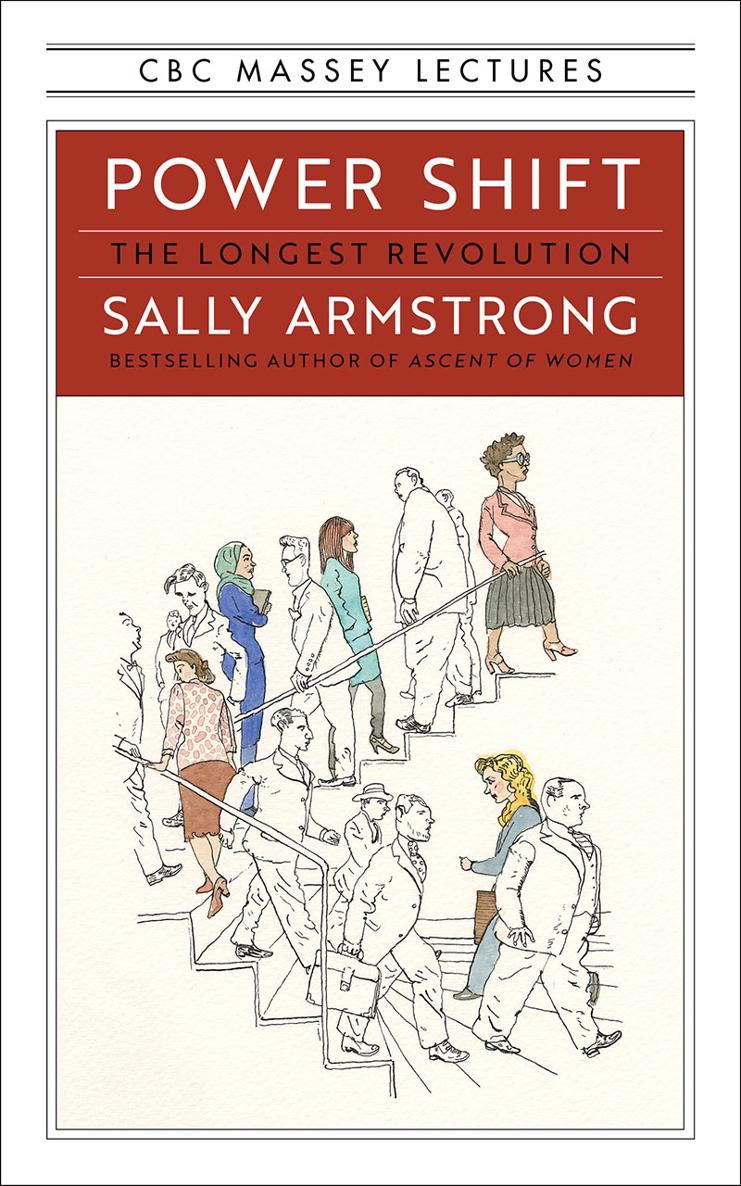

Cover design: Alysia Shewchuk

Cover illustration: Barry Blitt

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada.

For all the women and all the girls in all the world. This is our time.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: In the Beginning(s)

Chapter 2: The Mating Game

Chapter 3: A Holy Paradox

Chapter 4: When the Patriarchy Meets the Matriarchy

Chapter 5: Shifting Power

Notes

Permissions

Acknowledgements

Index

I know that many men and even women are afraid and angry when women do speak, because in this barbaric society, when women speak truly they speak subversively they cant help it: if youre underneath, if youre kept down, you break out, you subvert. We are volcanoes. When we women offer our experience as our truth, as human truth, all the maps change. There are new mountains.

Thats what I want to hear you erupting. You young Mount St. Helenses who dont know the power in you I want to hear you.

Ursula K. Le Guin

Chapter One

in the beginning(s)

So many beginnings. From delicate handprints on a cave wall to goddesses in ancient Mesopotamia; from political tyranny that came in the guise of a message from God to the convoluted journey to emancipation the story of women is the longest revolution in history. So many times change was in the wind. So many times the finish line blurred. And so many times hope soared. Still, from Toronto to Timbuktu, the promise of equality has eluded half the worlds population. Now theres a power shift. Theres never been a better time in human history to be a woman. And despite the blowback from misguided politicians, leftover chauvinists, and hypermasculine misogynists, women are closer to gaining equality than ever before. The journey ahead is bound to be epic, and it will affect everything our wallets, our jobs, our very future.

Why now? How come the power shift didnt happen during the first wave of the womens movement (18481920), when the suffragettes struggled to get the vote? Or the second wave (196380), when women put all our faith in the pill and attended consciousness-raising sessions that discussed the oppression of women and demanded change in the status of women? Or even the third wave (19922010), which began after the American lawyer and academic Anita Hill was called to testify at the televised confirmation hearing of U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, whom she had accused of sexual harassment, thus challenging his fitness for the position? Hill was then excoriated by the all-male Judiciary Committee, who didnt believe her, and Thomas was appointed to the Supreme Court. The fallout became a watershed moment in American politics and a turning point in raising awareness of sexual harassment. But still the long-term status of women was mostly unchanged.

Now with the fourth wave, a movement that began in 2012 when social media took off, theres a focus on intersectionality, a push for greater empowerment of traditionally marginalized groups Indigenous people, people of colour; LGBTQ; ethnic, religious, and cultural minorities; people with physical and developmental disabilities; people of differing social classes and for greater representation in politics and business. Fourth-wave feminists argue that society will be more equitable if policies and practices incorporate the perspectives of all people. While earlier feminists fought to shake off the ties that bound them to subservience, this new wave calls for justice against discrimination, assault, harassment, and it calls for equal pay and individual choices over our own bodies. Words like cisgender, non-binary, and polyamorous reflect the new vocabulary of a changing, more diverse society, and the clarion call for inclusion is being heard around the world.

This wave created hashtag feminism and put abusive powerful men on notice. And by all accounts, this one got liftoff. The symbiotic relationship between social media and individualism is likely driving the bus for change. The internet is all about instant. Twitter and Facebook can elevate people and create extreme celebrity and propel movements. Some of these, like #MeToo and #TimesUp, have been amplified by attention from influential entities such as the New York Times and the Hollywood film industry, but others have been simmering over the last decade. As a journalist, I have watched human rights and the rights of women and girls become the focus of conversation, whether in the forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo or the savannah in Kenya, in the deserts of Afghanistan or the college campuses in North America.

We have always depended on political will to change up the agenda the stroke of the politicians pen to install the stop sign or build the shelter or legislate a new law. It often took public will marches and petitions to push the politician to make change happen. But in the last few years, Im seeing what I call personal will as the driving force behind both public and political will. Malala Yousafzai is a good example. She was fifteen years old, living in the Swat Valley in Pakistan; she wanted to go to school to learn to think for herself. But the Taliban, who claim they act in the name of God, forbade education for girls. She defied the cowardly thugs by speaking out publicly on girls rights to an education. On October 8, 2012, she climbed onto the school bus. The last words she heard were: Which one is Malala? The Taliban gunman shot that child in the head for going to school. But Malala recovered, and then she started a movement. Today everyone knows her. Shes become the worlds daughter, not because a politician in the Swat Valley insisted that the girls go to school; not because there were marches and petitions demanding education for girls. It was personal will that propelled Malala.