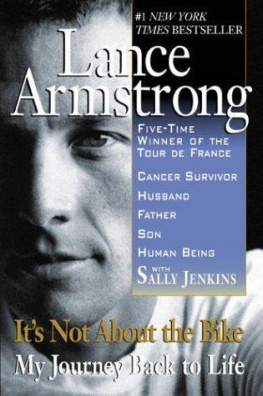

what a true champion is. Kik, for completing me as a man. Luke, the greatest gift of my life, who in a split second

made the Tour de France seem very small. All of my doctors and nurses. Jim Ochowicz, for the fritters... every day. My teammates, Kevin, Frankie, Tyler,

George, and Christian. Johan Bruyneel. My sponsors. Chris Carmichael.

Bill Stapleton for always being there. Steve Wolff, my advocate. Bart Knaggs, a mans man.

JT Neal, the toughest patient cancer has ever seen. Kelly Davidson, a very special little lady. Thorn Weisel. The Jeff Garvey family.

The entire staff of the Lance Armstrong Foundation. The cities of Austin, Boone, Santa Barbara, and Nice. Sally Jenkinswe met to write a book but you became a dear friend along the

way.

The authors would like to thank Bill Stapleton of Capital Sports Ventures and Esther Newberg of ICM for sensing what a good match we would be and bringing us together on this book.

Stacy Creamer of Putnam was a careful and caring editor and Stuart Calderwood provided valuable editorial advice and made everything right. Were grateful to ABC Sports for the

comprehensive set of highlights, and to Stacey Rodrigues and David Mider for their assistance and research. Robin Rather and David Murray were generous and tuneful hosts in Austin.

Thanks also to the editors of Womens Sports and Fitness magazine for the patience and backing, and to Jeff Garvey for the hitched plane ride.

nine

THE TOUR

LIFE IS LONGHOPEFULLY. BUT LONG IS A

relative term: a minute can seem like a month when youre pedaling uphill, which is why there are few things that seem longer than the Tour de France. How long is it? Long as a freeway

guardrail stretching into shimmering, flat-topped oblivion. Long as fields of parched summer hay with no fences in sight. Long as the view of three nations from atop an icy, jagged peak in the

Pyrenees.

It would be easy to see the Tour de France as a monumentally inconsequential undertaking: 200 riders cycling the entire circumference of France, mountains included, over three weeks in the

heat of the summer. There is no reason to attempt such a feat of idiocy, other than the fact that some people, which is to say some people like me, have a need to search the depths of their

stamina for self-definition. (Im the guy who can take it.) Its a contest in purposeless suffering.

But for reasons of my own, I think it may be the most gallant athletic endeavor in the world. To me, of course, its about living.

A little history: the bicycle was an invention of the industrial revolution, along with the steam engine and the telegraph, and the first Tour was held in 1903, the result of a challenge in the

French sporting press issued by the newspaper LAuto. Of the sixty racers who started, only 21 finished, and the event immediately captivated the nation. An estimated 100,000 spectators

lined the roads into Paris, and there was cheating right from the start: drinks were spiked, and tacks and broken bottles were thrown onto the road by the leaders to sabotage the riders chasing

them. The early riders had to carry their own food and equipment, their bikes had just two gears, and they used their feet as brakes. The first mountain stages were introduced in 1910 (along

with brakes), when the peloton rode through the Alps, despite the threat of attacks from wild animals. In 1914, the race began on the same day that the Archduke Ferdinand was shot. Five

days after the finish of the race, war swept into the same Alps the riders had climbed. Today, the race is a marvel of technology. The bikes are so light you can lift them overhead with one hand,

and the riders are equipped with computers, heart monitors, and even two-way radios. But the essential test of the race has not changed: who can best survive the hardships and find the

strength to keep going? After my personal ordeal, I couldnt help feeling it was a race I was suited for.

Before the 99 season began, I went to Indianapolis for a cancer-awareness dinner, and I stopped by the hospital to see my old cancer friends. Scott Shapiro said, So, youre returning to stage

racing?

I said yes, and then I asked a question. Do you think I can win the Tour de France?

I not only think you can, he said. I expect you to.

BUT I KEPT CRASHING.

At first, the 1999 cycling season was a total failure. In the second race of the year, the Tour of Valencia, I crashed off the bike and almost broke my shoulder. I took two weeks off, but no

sooner did I get back on than I crashed again: I was on a training ride in the south of France when an elderly woman ran her car off the side of the road and sideswiped me. I suffered like

the proverbial dog through ParisNice and Milan-San Remo in lousy weather, struggling to mid-pack finishes. I wrote it off to early-season bad form, and went on to the next racewhere I

crashed again. On the last corner of the first stage, I spun out in the rain. My tires went out from under me in a dusky oil slick and I tumbled off the bike.

I went home. The problem was simply that I was rusty, so for two solid weeks I worked on my technique, until I felt secure in the saddle. When I came back, I stayed upright. I finally won

something, a time-trial stage in the Circuit de la Sarthe. My results picked up.

But it was funny, I wasnt as good in the one-day races anymore. I was no longer the angry and unsettled young rider I had been. My racing was still intense, but it had become subtler in style

and technique, not as visibly aggressive. Something different fueled me nowpsychologically, physically, and emotionallyand that something was the Tour de France.

I was willing to sacrifice the entire season to prepare for the Tour. I staked everything on it. I skipped all the spring classics, the prestigious races that comprised the backbone of the

international cycling tour, and instead picked and chose only a handful of events that would help me peak in July. Nobody could understand what I was doing. In the past, Id made my living in

the classics. Why wasnt I riding in the races Id won before? Finally a journalist came up to me and asked if I was entered in any of the spring classics.

No, I said.

Well, why not?

Im focusing on the Tour.

He kind of smirked at me and said, Oh, so youre a Tour rider now. Like I was joking.

I just looked at him, and thought, Whatever, dude. Well see.

Not long afterward, I ran into Miguel Indurain in a hotel elevator. He, too, asked me what I was doing.

Im spending a lot of time training in the Pyrenees, I said.

Porque? he asked Why?

For the Tour, I said.

He lifted an eyebrow in surprise, and reserved comment.

Every member of our Postal team was as committed to the Tour as I was. The Postal roster was as follows: Frankie Andreu was a big, powerful sprinter and our captain, an accomplished

veteran who had known me since I was a teenager. Kevin Livingston and Tyler Hamilton were our talented young climbing specialists; George Hincapie was the U.S. Pro champion and

another rangy sprinter like Frankie; Christian Vandevelde was one of the most talented rookies around; Pascal Derame, Jonathan Vaughters, and Peter Meinert-Neilsen were loyal domestiques

who would ride at high speed for hours without complaint.

The man who shaped us into a team was our director, Johan Bruyneel, a poker-faced Belgian and former Tour rider. Johan knew what was required to win the Tour; he had won stages twice