PROLOGUE

The Souths

Strangest Soldier

1921, Border of Jones and Jasper Counties, Mississippi

T he newspaperman drove his big city car along a rutted red-clay country road, sending up garlands of Mississippi backwoods dust. Newton Knight was hard enough to find when he was living. Dead, he would always be a fugitive, the newspaperman supposed. The old Civil War guerrilla was said to be nearing ninety years of age, and it wouldnt be long before he escaped his worldly pursuers and went to the graveand plunged straight to hell, his enemies hoped. But before he did, the newspaperman intended to take down his story with an honest pen.

The chance to interview Knight was an irresistible summons to Meigs O. Frost. An Andover- and Harvard-educated correspondent for the New Orleans Item, Frost, thirty-eight, was always on the lookout for a rich subject. Hed made a career out of exploring the queer angle, the surprising complication, and the buried secret. Newton Knight qualified on all of these counts; there wasnt a more controversialor reclusive Civil War figure in the South. Hed still be debated long after the last headstone of the oldest combatant was covered with moss, Frost guessed.

Frost pressed the gas of his black Model T and endured the jouncing of his wheels, the rattling of the shutter hood, and laboring of the crankshaft. The rough road, littered with stones and pine boughs, wound through steep, wooded fields and across the crest of a lonesome timber-covered ridge. At last, a clearing opened up. Frost braked to a stop, with a sound of ahooga from the brass horn. He sat on the cape of a remote hill, with a sentinel-like view of the surrounding ridges. It was a place that suggested guardedness rather than peace.

Before him was a weather-beaten cabin, sheltered by lofty pines and crooked oaks, the sort the Confederate cavalry had hung traitors from. Frost got out of the car, and as the dust swirled around his cuffed pants and city shoes, he felt a stir of anticipation. He just might get the answers to some long-asked questions. Everyone had an opinion about the man whose loyalty to the Union had caused him to betray the South. But no one had ever heard the opinions of Newton Knight himself.

Knights role in Civil War Mississippi had been argued over ever since the surrender. The debate as to who he was and what he meant by his actions raged on, in old letters in school-taught hands, overlooked depositions, and wartime documents. Only one characteristic of the man did they all agree on.

Just a fightin fool when he got started, a friend described him.

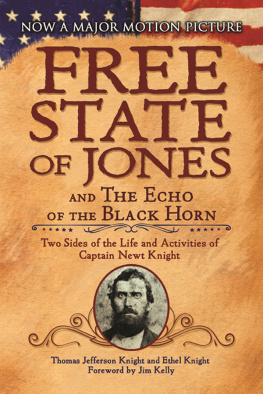

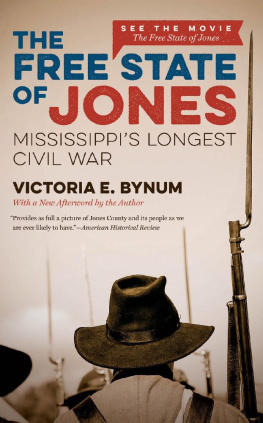

From 1863 to 1865, Knight, an antislavery farmer in Jones County, Mississippi, led an insurrection against the Confederacy. For two long years he fought a war from within, successfully evading every bloodhound and tough-booted rebel that came after him. Working side by side with blacks and fellow fugitives, he raised the American flag in the marrow of the South, Confederate president Jefferson Daviss home state, and became such an effective opponent that in the last year of the war exaggerated reports circulated that he and his compatriots seceded from the Confederacy and formed a separate government. The phrase The Free State of Jones earned a storied if apocryphal place in Mississippi, and in the American imagination.

For all of that, Captain Newton Knight remained one of the less known and most poorly understood warriors of the Civil War. An expert in the art of disappearance, he had faded into the weeds of time the way he once faded into the canebrake of the Mississippi Piney Woods region. Virtually every local account of him was bent by lore or bitter memory. Depending on who told the story, he was called a hero, outlaw, soldier, or murderer.

I believe in giving the devil his due, Newt was a mighty sorry man, declared his old Confederate neighbor, Ben Graves.

Yet, to one local boy named Monroe Johnson, Knight left the indelible impression of a patriot. He looked, Johnson said, like George Washington, with his long white hair.

Who was he, really?

He was a slave owners grandson who never owned slaves; a dead-eyed shot who could reload a shotgun before the smoke cleared; a father and husband who after the war had two families, one white, the other black; a white man who in his later years was called a Negro. He fought for racial equality during the war and after, and he envisioned a world that would only begin to be implemented a century later.

Those were the facts. The full story was even more complicated.

That Newton Knight deserted and fought against the Confederate army was well known. Less well known, and seldom publicly acknowledged was Newtons long alliance with a woman named Rachel, a slave owned by his family, a woman of manifest strength and arresting appearance whom he was rumored to have loved, and even married. Rachel aided and protected Newton during the Civil War and after it bore his children. Newton shared his homestead with her until her death in 1889, and perhaps breaking the biggest taboo of all, he had acknowledged their children and grandchildren as his own. What he did after the war was worse than deserting, old Ben Graves said.

The recovery of the life of this poor Mississippi farmer who fought for the Union was an important story, Frost believed. For one thing, Knight contradicted the romantic vision of the Southern past as a glorious Lost Cause. In this view, the Confederacy was a noble but failed attempt to declare independence from Northern aggressorsand slavery was ignored. One would never know, based on this Lost Cause mythology, that countless gallant Confederate heroes had committed treason, in defense of a still deeper crime. Or that the majority of white Southerners had opposed secession, that many Southern whites fought for the Union, and that a few of them, like Knight, burst free of racial barriers and forged bonds of alliance with blacks that were unmatched even by Northern abolitionists, and remained loyal against all odds.

Newton Knight was a spectacular reminder to Meigs Frost that the South was plagued by bloody internal estrangements. In fact, a major reason for the Souths defeat stemmed from its enemies within, blacks and whites. In Jones County, fifty-three men had not only fought as anti-Confederate guerrillas, but formally enlisted in the Union army in New Orleans.