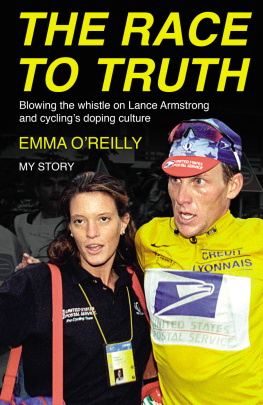

David Walsh is chief sportswriter with the Sunday Times. A four-time Irish Sportswriter of the Year and a three-time UK Sportswriter of the Year, he is married with seven children and lives in Cambridge. He is co-author of L.A.Confidential: The Secrets of Lance Armstrong and author of From Lance to Landis: Inside the American Doping Controversy at the Tour de France.

Winner of the British Sports Book Awards Biography of the Year

Shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year

Winner of the Bord Gis Irish Book Awards Sports Book of the Year

Fascinating... a gripping tale of one mans determination

Sunday Mirror

Not so much a valuable as an essential book for anyone interested in Armstrong, bike racing or doping

New Statesman

One of the most powerful sports books ever written

sportsbookofthemonth.com

Also by David Walsh

Inside Team Sky

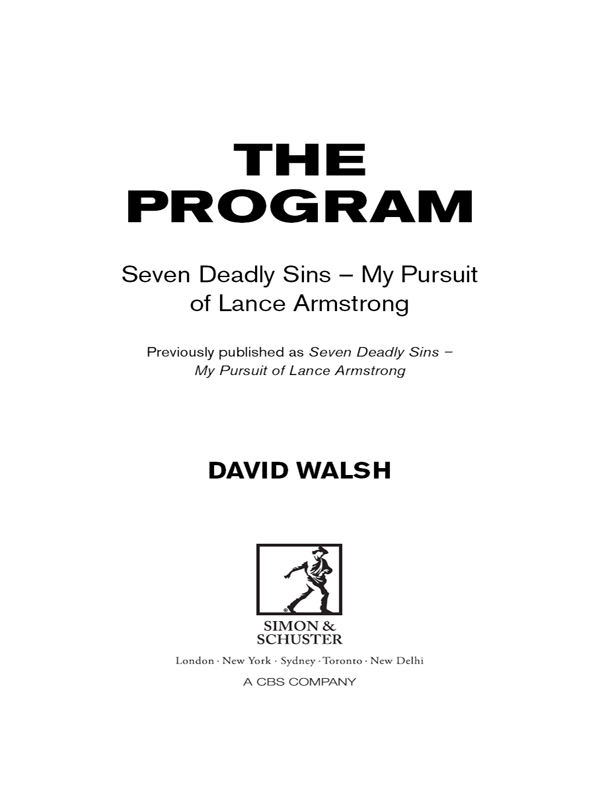

First published in Great Britain as Seven Deadly Sins by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2012

This paperback edition published by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2015

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright David Walsh 2012, 2013

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of David Walsh to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London

WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

Every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material reproduced in this book. If any have inadvertently been overlooked, the publishers would be glad to hear from them and make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-4711-5258-0

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-4711-5562-8

Typeset by M Rules

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd are committed to sourcing paper that is made from wood grown in sustainable forests and supports the Forest Stewardship Council, the leading international forest certification organisation. Our books displaying the FSC logo are printed on FSC certified paper.

For John, his brothers, his sisters and mum

I watch the Olympic Games but I dont bother to remember the names of the athletes any more. Its like theatre but I prefer the theatre because the relationship between actor and spectator is clear. In sports theatre, both are still pretending its real.

Sandro Donati

Youre no messiah. Youre a movie of the week. Youre a fucking T-shirt, at best.

Brad Pitt, Se7en

Contents

Prologue

Finally, the last thing, Ill say to the people who dont believe in cycling, the cynics and the sceptics: Im sorry for you. Im sorry that you cant dream big. Im sorry you dont believe in miracles.

Lance Armstrong, 2005 Tour de France victory speech

Le grand depart.

My first conversation with Lance Armstrong was in the garden of the Chateau de la Commanderie hotel about ten miles south of Grenoble. This was late afternoon on Tuesday 13 July 1993, a rest day on the Tour de France, and with its trees and shrubs, its wrought-iron chairs and tables overlooking the swimming pool, the setting couldnt have been much better.

At a nearby table, Armstrongs teammate Andy Hampsten sat with some friends. A little further away, another journalist interviewed the teams Colombian climber, lvaro Meja. Armstrong and I sat in the shade and spoke for more than three hours. He did most of the talking, but then he had much to say and I had a book to write.

It was the force of his personality that struck you the most: like a wave crashing forward and carrying you with him. Twenty-one years old but he wasnt like most young men of that age. If he had been, he would have talked about the thrill of riding his first Tour de France. Most young sportsmen know the clichs that we like to see recycled. He didnt mention the thrill or the honour, nothing even close. Hed been told by the team bosses he was at this Tour to learn for the future, but he didnt see the good in that. He wanted to win right now. I am Lance Armstrong, youre gonna remember my name. As he machine-gunned his way through his past and speeded into the future, he had me at his side, and on his side.

Youve got to see this kid, I said over dinner to my friend, fellow journalist and former Tour rider Paul Kimmage, that evening.

Why?

He is different. Hes got this desire. Hes going to win a lot of races, and hes so open. Wait til you meet him.

You always get too enthusiastic, Kimmage said.

Eleven years earlier, Id turned up at the Tour de France for the first time and fallen in love. The man-crush is a hazard of life for the sportswriter. That debut trip covered just the last two race days in 1982; the boat from Rosslare in the south-east of Ireland to Le Havre, a car drive to pick up the penultimate stage and then on into Paris for the race to the Champs-lyses. I travelled with four people from Carrick-on-Suir, the home town of Sean Kelly, who was then one of the worlds best cyclists. Kellys fiance Linda Grant was part of our group, as was her father Dan, and local shopkeeper Jim OKeeffe. Professional cycling wasnt big news in Ireland then, and if Kelly managed to win a stage in the Tour de France, the result just about made it onto a sports page. Down in Carrick-on-Suir, OKeeffe was ahead of the rest of us because he knew how to tune his radio into some French station that gave regular updates from the Tour, and if the local hero did well, the local shopkeeper knew it first.

One afternoon OKeeffe caught news of Kelly winning a stage at the Tour, it might have been the leg to Thonon in 1981. Beside himself with joy, he left his shop and just walked down Main Street hoping to meet someone he could tell. Coming in the opposite direction was Kellys Uncle Neddy, wheeling his bicycle.

Neddy, said OKeeffe, youre not going to believe this. Im just after hearing Sean won todays stage in the Tour de France.

Taking a second to digest the news, Neddy replied, Why wouldnt he win, he does nothin else except cycle that bike.

Telling Irish people that they had produced a world-class athlete called Sean Kelly became my first crusade. But in terms of the Irish attitude to Kellys prowess, things didnt change quickly, and the following year I could get to the Tour de France only by taking two weeks holiday and the considerable risk of travelling on the back of Tony Kellys BMW 1000 motorbike. On a clear road Tony could get that baby up to 130 mph, and whatever happened, I knew it wouldnt take long. We saw Kelly take the yellow jersey in Pau, found a cheap restaurant and toasted his achievement with a bottle of wine.

Stephen Roche, our other countryman in the race, had the white jersey for the leading young rider and that evening in the Basque city we felt proudly Irish, members of a privileged elite. Next day we waited on the Col de Peyresourde and measured the scale of disaster by the minutes Kelly and Roche lost to the new leaders. As hard as it was to see your men wither in the mountains, it was impossible not to be captivated by the great race beyond them. The Tour thrilled me like no other sporting event, and no sooner had Tony returned me to Dublin I was talking to my wife about how good it would be to move to France. So in 1984, Paris became home and I got to follow most of the great races on the cycling calendar.

Next page