To my two greatest loves, Dave and Allegra

To my heroes, Mama and Tata

This is my body. And I can do whatever I want to it. I can push it, study it, tweak it, listen to it. Everybody wants to know what Im on. What am I on? Im on my bike, busting my ass six hours a day. What are you on?

LANCE ARMSTRONG

CONTENTS

T he $10 million estate of Lance Armstrongs dreams is hidden behind a tall, cream-colored wall of Texas limestone and a solid steel gate. Visitors pull into a circular driveway beneath a grand oak tree whose branches stretch toward a 7,806-square-foot Spanish colonial mansion.

The tree itself speaks of Armstrongs famous will. It once was on the other side of the property, fifty yards west of this house.Armstrong wanted it at the front steps. The transplantation cost $200,000. His close friends joke that Armstrong, who is agnostic, engineered the project to prove he didnt need God to move heaven and earth.

For nearly a decade, Lance Armstrong and I have had a contentious relationship. Seven years have passed since his agent, Bill Stapleton, first threatened to sue me. Back then, I was just one of the many reporters Armstrong had tried to manipulate, charm or bully. Filing lawsuits against writers who dared challenge his fairy-tale story was his quick-and-easy way of convincing people that writing critically about him wasnt worth it. Over the years, he came to consider me an enemy, one of the many he and his handlers had to keep an eye on.

Only now, after he has fallen, have we agreed to something approaching a truce. Though hed deny it, I know that he has chosen to sit down with me because he thinks he might be able to control the direction of my book. No chance, Ive told him. After multiple criminal and civil investigations into whether Armstrong orchestrated a sophisticated doping regime to win seven Tour de France titles; after all the testimonies from riders who knew him better than anyone else, and who contradicted under oath every public defense Armstrong had ever given; after he lied, lied and lied some more, the most notorious athlete of our generation realizes Im suddenly holding a lot of rope. And I realize that, even now, he imagines himself to occupy a position of almost absolute power.

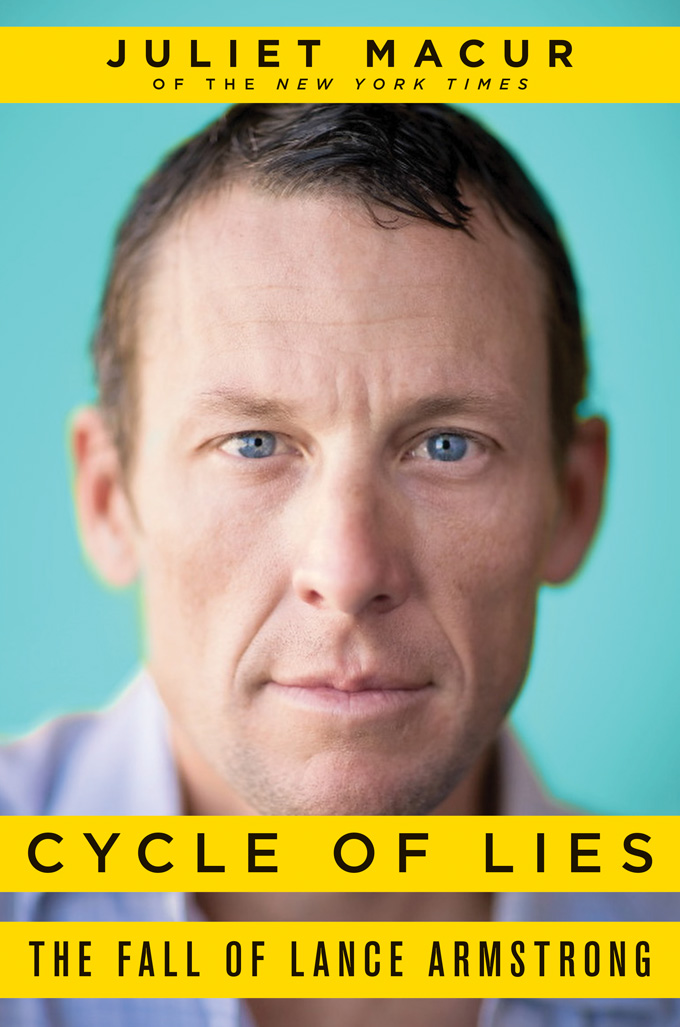

You can write what you want, he tells me in one of our many conversations. But your book is called Cycle of Lies ? That has to change.

Ive interviewed him one-on-one in five different countries; on team buses that smelled of sweat-soaked Lycra at the Tour de France, in swanky New York City hotel rooms, in the backs of limos, in soulless conference rooms; and for hours by telephone.

Now, in the spring of 2013, after his whole world has come crashing down and moving trucks are en route to dismantle his beloved estate, Ive come to visit him at home in Austin, Texas, for the first time.

Yes, fine, come on out, he said. Beset by endless obituaries of his celebrated (and now fraudulent) career, he wanted to ensure that I wrote the true story.

So here I am parking beneath the grand oak that Armstrong had moved because, why not? I look at the house and think of his yellow jerseys. A month after the United States Anti-Doping Agency released 1,000 pages of evidence against Armstrong and stripped him of his Tour titles, he had Tweeted a photo of himself lounging, arrogance itself, on an L-shaped couch in this house, his seven yellow jerseys hanging ceremoniously behind him: Back in Austin and just layin around. That was November 2012. Seven months later, will I find him still defiant?

Before I can pull the keys from my cars ignition, a cherubic face under tousled, curly brown hair appears at my window and two small preschooler hands slap the glass. Its Lances youngest son, Max.

Armstrong stands behind him in flip-flops, wearing a black T-shirt over black basketball shorts that brush his scarred knees. His eyes are hidden by dark sunglasses.

Say hi to Juliet, Max, Armstrong says.

Hi, Joo-leee-ette! Max says. Then he turns to his dad and asks for ice cream, a request that makes his father giggle, something Id never seen him do before.

Yes, you get ice cream, Armstrong says. Youve been good, buddy, really good.

We walk up the front steps until Armstrong stops at the door. He moves his eyes to the tree, the house, the life he has enjoyed.

Great place, right? he says.

Yes, I say, are you going to miss it?

Armstrong doesnt want to move, he has to. His sponsors have abandoned him, taking away an estimated $75 million in future earnings. He would owe more than $135 million if he were to lose every lawsuit in which he is a defendant. To slow the burn rate, as he calls it, he has stopped renting a penthouse apartment on Central Park in Manhattan and a house in Marfa, Texas. Next to go is this Austin estate, traded in for a much more modest abode near downtown.

His former sponsorsincluding Oakley, Trek Bicycle Corporation, RadioShack and Nikehave left him scrambling for money. He considers them traitors. He says Treks revenue was $100 million when he signed with the company and reached $1 billion in 2013. Whos responsible for that? he asks. Fucking right here. He pokes himself in the chest with his right index finger. Im sorry, but that is true. Without me, none of that happens.

After his sponsors cast him aside, he tossed their gear. Theres a chance you could catch a glimpse of one of his Dallas friends wearing Armstrongs custom-made yellow Nike sneakers, with Lance embroidered in small yellow block letters on the shoes black tongues. A Goodwill outlet in Austin is replete with his former Nike clothes and Oakley sunglasses. The movers, who packed up his guesthouse a week before I visited, will have to contend with whatever brand-name gear is left in his garage: black Livestrong Nike caps, black Nike duffel bags with bright yellow swooshes, Oakley lenses and frames and a box of caps suggesting Yes on Prop 15, a 2007 Texas bond plan for cancer research, prevention and education supported by Armstrong.

It was 1989 when Armstrong moved to Austin from Plano, a suburb of Dallas, showing up in this progressive town as a rough, combative and pimply-faced teenager, with frosted wavy brown hair, a gold hoop in his pierced left ear, a silver chain around his neck with a dangling pendant in the shape of Texas, and a fake ID.

On an income of $12,000 a year, and with the help of a local benefactor named J.T. Neal who had taken Armstrong in, he lived in a studio apartment for $200 a month. He dressed it up with an oversized black leather couch, a matching chair and, above the fireplace, a red-white-and-blue colored skull of a Texas longhorn.

From a cramped studio to a sprawling estate: a reflection of Armstrongs ascension into modern American sainthooda cancer survivor who beat the worlds best cyclists in a grueling race, dated anyone he wanted and made millions in the process.

Armstrong loves this house. He loves its open spaces and floor-to-ceiling windows. He loves the lush, landscaped yard where his kids play soccer, and the crystalline pool (a negative-edge pool, not an infinity pool, get it right). Behind the house are rows of towering Italian cypresses.

He moved here in 2006 after winning a record seventh Tour de France. He once said the place was his safe houseinside it, nobodys going to mess with me. Having eluded near-constant attempts to expose his doping, he could take a left down the main hallway, then a quick right, and disappear into his walk-in wine closet to grab a bottle of Tignanello and toast his good luck.

On a table next to a couch is a 36-inch model of the Gulfstream jet that had been Armstrongs favored means of long-distance flight. Its white with black and yellow racing stripes. He and his buddies often stood up when the plane took off, surfing as it rocketed into the sky. Armstrong had sold the plane for $8 million in December 2012, as he braced himself for the inevitable legal fees that would follow USADAs expos of his cheating.