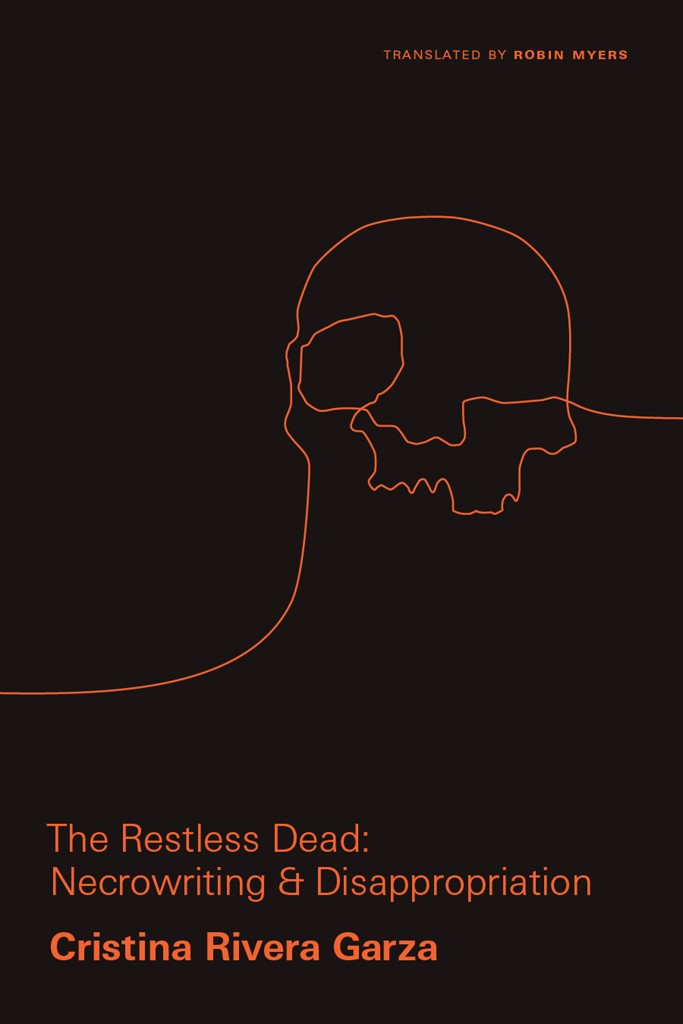

The Restless Dead

CRITICAL MEXICAN STUDIES

Series editor: Ignacio M. Snchez Prado

Critical Mexican Studies is the first English-language, humanities-based, theoretically focused, academic series devoted to the study of Mexico. The series is a space for innovative works in the humanities that focus on theoretical analysis, transdisciplinary interventions, and original conceptual framing.

The Restless Dead

Necrowriting & Disappropriation

Cristina Rivera Garza

Translated by Robin Myers

Vanderbilt University Press

Nashville, Tennessee

Translation copyright 2020 by Robin Myers.

Published 2020 by Vanderbilt University Press.

First printing 2020

Originally published in the Spanish as Los muertos indciles. Necroescritura y desapropiacin, copyright Cristina Rivera Garza, 2013, c/o Indent Literary Agency, www.indentagency.com. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rivera Garza, Cristina, 1964 author. | Myers, Robin, 1987 translator.

Title: The restless dead : necrowriting and disappropriation / Cristina Rivera Garza ; translated by Robin Myers.

Other titles: Muertos indociles. English

Description: Nashville : Vanderbilt University Press, [2020] | Series: Critical Mexican studies; book 1 | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020018702 (print) | LCCN 2020018703 (ebook) | ISBN 9780826501219 (paperback) | ISBN 9780826501226 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780826501233 (epub) | ISBN 9780826501240 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: AuthorshipSocial aspects. | TechnologySocial aspects. | Violence.

Classification: LCC PN149 .R58513 2020 (print) | LCC PN149 (ebook) | DDC 808.02dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020018702

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020018703

How much can a dead body experience?

Teresa Margolles

What is offered to us is that community is coming about, or rather, that something is happening to us in common. Neither an origin nor an end: something in common. Only speech, a writingshared, sharing us.

Jean-Luc Nancy,The Inoperative Community

To see the dead as the individuals they once were tends to obscure their nature. Try to consider the living as we might assume the dead to do: collectively. The collective would accrue not only across space but also throughout time. It would include all those who had ever lived. And so we would also be thinking of the dead. The living reduce the dead to those who have lived, yet the dead already include the living in their own great collective.

John Berger,On the Economy of the Dead

Contents

Acknowledgments

From 2006 to 2013, I wrote a weekly column of about 5,500 characters for the cultural section of Milenio, a newspaper of national circulation in Mexico. The Oblique Hand quickly became a laboratory of ideas where I explored wide-ranging topics and forms: from book reviews to translations, from travel chronicles to film analyses, from notes on contemporary art to discussions of current politics. Felipe Caldern became president, winning a hotly contested election by the slightest of margins. Immediately thereafter, he escalated the so-called War on Drugs: a long-lasting conflict with roots dating back to the late 1960s, when the Mexican state militarized counter-narcotic activities and thus paved the way for the organization of counterinsurgent groups targeting both guerrilla movements and drug traffickers from the 1970s onwards. The violence that spread across the country was hardly new to the early twenty-first century, but its spectacular cruelty defied any semblance of normalcy. Without a program in mind, I began reflecting on the war that engulfed our days and claimed so many lives. The first edition of The Restless Dead: Necrowriting and Disappropriation, published in Mexico in 2013, comprised a selection of the articles I devoted to exploring the fraught relationship between violence and writing. These were not academic pieces, but dispatches generated in a swiftly crumbling world, one I found increasingly difficult to explain with accepted truths or rusty tools. I wrote freely, in a style amenable to broader audiences regardless of the complexity, or obscurity, of the subject in question. In my mind, The Restless Dead remains a book of writing activism.

In 2008, during one of the gravest financial crises in recent years, I accepted a position as a professor in the MFA program in creative writing at the University of California, San Diego. I continued publishing The Oblique Hand on a weekly basis, but this time I was reporting from the Tijuana-San Diego border, one of the most dynamic geopolitical crossings in the world. I became a migrant in my two countries, perpetually moving back and forth. And back. Although theyre growing in number, creative writing programs remain scarce in Latin America, where most writers harbor deep-seated suspicion toward, if not outright dismissal of, the connection between writing and academia. Immersed in the US creative writing world for the first time, and writing mostly for Spanish-speaking audiences in Mexico, I used my column to explore the pros and cons of historically divergent approaches to teaching and practicing writing. In recent decades, grants funded by the Mexican state have played a greater role in supporting younger writers. Until very recently, though, gender and racial discrimination have been the uncontested norm in writing programs taught outside academic environments, and with very little accountability, in Mexico.

While I was able to develop a writing life in Spanish while teaching in English in Southern California, the marginalization of Spanishand, more generally, of writers of color in US writing programsproved overwhelming, and especially troubling on the UC campus in greatest geographical proximity to the US-Mexico border. Spanish majors at US campuses deemed Hispanic-Serving Institutions, such as UC Riverside and Santa Barbara, numbered 250 students. At UC San Diego, however, only about twenty-five students declared Spanish as their major in 2016. Meanwhile, students from the Spanish-speaking world entering the MFA program as bilingual writers soon learned that the institution offered English-only courses and only admitted theses written in English. Through this perverse act of erasure, the university paid lip service to the cultural and aesthetic relevance of Spanish while actively ensuring that both the language and its practitioners remained invisible or inconsequential in classrooms and hallwaysand, even more importantly, in the writing valued by the system. As is true in universities countrywide, tenure appointments and salary raises continue to dismiss the relevance of work written in languages other than English, often arguing that committee members lack the credentials and linguistic skills to objectively evaluate the standing of publishing ventures abroad. Both the university and society as a whole lose out when people of color are thus impeded from contributing their input, talent, energy, and skills (linguistic and otherwise). As the poet Claudia Rankine has conveyed so electrifyingly in her book