Rhythmanalysis

Bloomsbury Research Methods

Edited by Graham Crow

The Bloomsbury Research Methods series provides authoritative introductions to a range of research methods which are at the forefront of developments in a range of disciplines.

Each volume sets out the key elements of the particular method and features examples of its application, drawing on a consistent structure across the whole series. Written in an accessible style by leading experts in the field, this series is an innovative pedagogical and research resource.

Also available in the series

Community Studies , Graham Crow

Diary Method , Ruth Bartlett and Christine Milligan

GIS , Nick Bearman

Inclusive Research , Melanie Nind

Qualitative Longitudinal Research , Bren Neale

Quantitative Longitudinal Data Analysis , Vernon Gayle and Paul Lambert

Forthcoming in the series

Embodied Inquiry , Jennifer Leigh and Nicole Brown

Statistical Modelling in R , Kevin Ralston, Vernon Gayle, Roxanne Connelly and Chris Playford

Rhythmanalysis

Research Methods

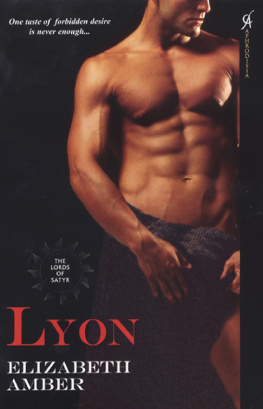

Dawn Lyon

Contents

Images

Sybil Andrews, Rush Hour , 1930, linocut on paper, EP 1, Collection of Glenbow; bequest of Sybil Andrews, 1995. Image copyright the Estate of Sybil Andrews, Glenbow, Calgary, Canada, 2017. |

Rue Rambuteau 30 and 24, Paris 3e, and view towards Centre Pompidou, 23 September 2017 (Authors own images). |

Tides, Isle of Sheppey, UK, 28 May 2017 (Authors own images). |

Seen from the coach window, inside and outside, 2007 (Tim Edensor, with kind permission). |

Stills from Billingsgate Fish Market, Dawn Lyon and Kevin Reynolds, 11 December 2012: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nw_kf32GfHY (Authors own images). |

Concertina journey by Tea, By The Way , 1999 (with kind permission of Peter Hatton). |

Table

Lefebvres vocabulary of rhythm summary of keyterms. |

The idea behind this book series is a simple one: to provide concise and accessible introductions to frequently used research methods and of current issues in research methodology. Books in the series have been written by experts in their fields with a brief to write about their subject for a broad audience.

The series has been developed through a partnership between Bloomsbury and the UKs National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM). The original What is? Research Methods Series sprang from the eponymous strand at NCRMs Research Methods Festivals.

This relaunched series reflects changes in the research landscape, embracing research methods innovation and interdisciplinarity. Methodological innovation is the order of the day, while still maintaining an emphasis on accessibility to a wide audience. The format allows researchers who are new to a field to gain an insight into its key features, while also providing a useful update on recent developments for people who have had some prior acquaintance with it. All readers should find it helpful to be taken through the discussion of key terms, the history of how the method or methodological issue has developed, and the assessment of the strengths and possible weaknesses of the approach through analysis of illustrative examples.

This book is devoted to rhythmanalysis. In it, Dawn Lyon provides an account of a methodological innovation inspired by the work of Henri Lefebvre, whose broad thinking is not easy to classify, spanning as it does several decades and many disciplines. His project of revealing the ways in which everyday social life is patterned by rhythms that in the normal course of things remain hidden has proved stimulating to researchers in fields as diverse as tourism, high-frequency trading, music festivals, social welfare in the night-time city, and everyday conversation (among many others). Rhythmanalysis is not like research methods that can be learnt and then applied in a more or less standard fashion, because it involves active engagement by the researcher with the rhythms under investigation, and the exercise of creativity in order to capture and then convey them. The diversity of forms in which rhythmanalytical research has been published confirms the centrality of this creative element, and Lyons account conveys how new and inventive practices are being developed all the time. What holds them all together as a body of work is the researchers commitment to the search for temporal patterning in social activity which may be missed in both the first impressions of a newcomer and the perceptions of a person with greater familiarity. The new science that Lefebvre sought to found was envisaged like all sciences to be a means of making discoveries, and the record of research to date in this tradition that Lyon describes has repaid the faith of its practitioners in its potential to do this.

The books in this series cannot provide information about their subject matter down to a fine level of detail, but they will equip readers with a powerful sense of reasons why it deserves to be taken seriously and, it is hoped, with the enthusiasm to put that knowledge into practice.

Many people shaped and supported the development of this book. In particular I would like to thank Giulia Carabelli, Graham Crow, Tim Edensor, Steve Grix, Phil Hubbard, Ellie Jupp, Carolyn Pedwell, Lynne Pettinger, Chris Pickvance, Erin Sanders-McDonagh and Tim Strangleman as well as other colleagues at the University of Kent and anonymous reviewers for their comments, insights and encouragement.

Introduction: Why rhythmanalysis and why now?

Theres a scene that has stayed with me from when I lived in Italy in the early 2000s. I would often pass a small grocery shop in the centre of Florence on my way to catch a bus to work early in the morning when the shop was first opening, or in the late afternoon when trade has resumed. State regulation stipulates the clock-time of operating hours but this collective schedule also resonates with temporal norms of meal times and rest which leave room for the cyclical rhythms of the body, the household and the social life of the city. As I walked along the Via dellAlbero, I frequently saw a young man who was part of the family grocery business on the threshold of the shop talking to someone in the street friends, fellow shopkeepers or customers it seemed and I would also stop to say hello and exchange a few words when our paths and pace converged. The conversation had its own form and rhythm and shoppers were sometimes made to wait while it came to its conclusion. I can now see the constellations of rhythms that gave rise to these moments of coming together in time and space, on the street but not quite, the young man at work but sidestepping its totalizing hold, myself on the way to work but out of step with the days trajectory in this encounter. The patience and accommodation of the shoppers feels important too; a collective refusal perhaps of the imposition of the linear rhythms of exchange and a tactic to retain a quality of everyday life that encompasses pleasure and meaning.

This book is concerned with understanding social life through the lens of rhythm. It emerged from my long-standing interest in how time and space are lived, produced, remembered and imagined, and how they shape the experience of everyday life as in the scene recounted above. Rhythm, it now seems, stimulated my curiosity beneath the surface in a series of projects in recent years. In a study of construction work, I was spellbound by the working rhythms of a man laying screed on a floor which he literally smoothed into shape through a combination of visual judgement and the graceful movement and pressure of his hands and body (Lyon 2012). And I can still bring to mind the sounds of fishmongers at work in a south London market as their gestures in chopping and filleting fish produced their own rhythm which could be heard all around bang, bang, slice, pause (Lyon and Back 2012). In these studies, I was interested in the reach and coordination of work across practices, people and things in time and space at different scales, such as the timing of laying screed in the refurbishment project or the sourcing of Caribbean fish to suit the tastes of the markets local customers. Rhythm finally came to the fore in my visual ethnography of Billingsgate fish market as I sought and struggled to identify the different coexisting spatial and temporal relations of market life. It was this project with all its surprising turns which prompted me to use and reflect on the potential of rhythmanalysis as a research strategy and a set of practices in the field (Lyon 2016 and see Chapter 3 for a discussion of this study). In this book, I explore what it means to undertake empirical research when attention to the flow and form of rhythm comes into view (Benveniste 1966).