The Joy of Noh

The Joy of Noh

Embodied Learning and

Discipline in Urban Japan

KATRINA L. MOORE

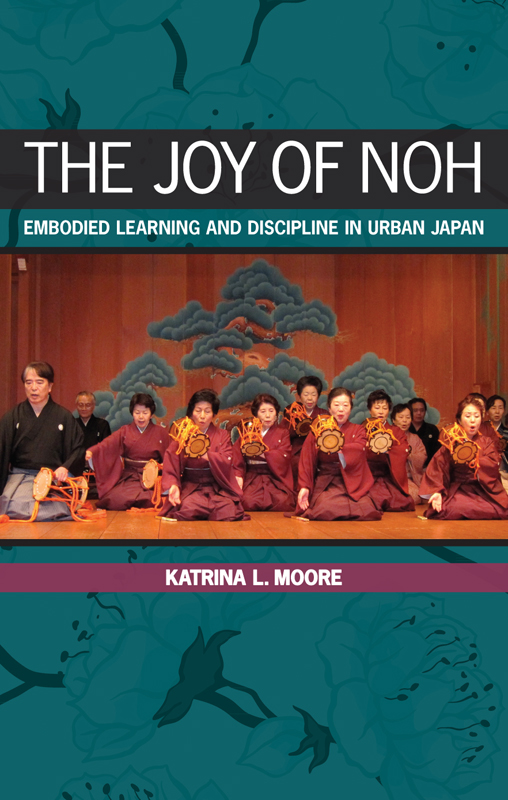

Cover image: Katrina L. Moore

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2014 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Jenn Bennett

Marketing by Anne M. Valentine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moore, Katrina L.

The joy of noh : embodied learning and discipline in urban Japan / Katrina L. Moore.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5059-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Noh. 2. Women in the theaterJapan. 3. WomenJapanSocial conditions. 4. ActingStudy and teachingJapan. I. Title.

PN2924.5.N6M57 2014

792.082dc23

2013019517

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my parents, Atsuko and Ian Roger Moore

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Writing a book incurs many debts. I would like to express my profound thanks to the many people who supported me as I conducted my field research and wrote this book.

As an ethnographer, I rely on the willingness of people to share their lives with me. I owe my greatest debt to the people in Japan who allowed me to become a part of their lives. I would like to say a special word of appreciation to Kobayashi Sayu, Koei Hoshino, Miki Yukiko, Nishii Aya, Tada Yoshiko and Tada Kunio, and Tsutsumi Yumiko and Tsutsumi Yoshihiko. I thank each of them for giving so generously of their time and for opening many doors that facilitated the development of this research.

At Harvard University, I was fortunate to have on my doctoral committee Theodore C. Bestor, Helen Hardacre, and Arthur Kleinman. I thank them for their unwavering support in all aspects of my work, and for critical comments and encouragement to take my work in new and challenging directions. Theodore C. Bestors ability to keep a finger on multiple threads of investigation, along with his strong commitment to ethnography, has inspired my work. I owe profound thanks to Helen Hardacre for her intellectual guidance and sustained moral support throughout my years of graduate school. She continues to be an inspiration and role model. My sincere gratitude goes to Arthur Kleinman, whose generosity as a mentor and keen analytical insights have been invaluable.

My colleagues at the University of New South Wales have been generous with their time and insights. I wish to thank especially Tanya Jakimow, Amanda Kearney, Vicki Kirby, Andrew Metcalfe, Michael Pusey, Louise Ravelli, Claudia Tazreiter, Carla Treloar, Melanie White, Marc Williams, and Mary Zournazi. I have also discussed some of these ideas in seminars at the University of New South Wales. Students in my seminars at the University of New South Wales offered engaging and thought-provoking feedback. Their insights and responses to the seminars have helped to inspire the writing of this book.

I wish to thank various friends and colleagues who provided inspiration and support during the writing of this book: Margaret Bruce, Manduhai Buyandelger, Ruth Campbell, John-Daniel Encel, Alisa Freedman, Junko Maria Furugori, Marilyn Goodrich, Zahra Jamal, Vera Mackie, Bakirathi Mani, Priscilla Song, Helen Snively, Rebecca Suter, Sarah Wagner, Allison Alexy, Joshua Dasey, Ivan Goldberg, Sue Hilditch, Lindsey Morse, Ursula Rao. and Sarah Teasley.

I would like to acknowledge the generous research support of the following: the Japan Foundation, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University, Cora Dubois Fund, and the University of New South Wales Research Promotion Grant. Sections of of this book appeared in the following journal article: Transforming Identities through Dance: Amateur Noh Performers Immersion in Educational Leisure Japanese Studies 33, no. 3 (2013): 263277. For permission to publish photographs of Noh performances, I gratefully acknowledge Kobayashi Kan who has made photographs available for this book.

I would like to thank Nancy Ellegate at the State University of New York Press for her enthusiastic support and sage advice in the revision of this manuscript, and Jenn Bennett for her expert help in preparing the manuscript for production.

I am very grateful to the reviewers of the original manuscript for their insightful comments and many constructive suggestions.

I thank my family for their love and affection. I would like to express my deep and enduring gratitude to my parents, Atsuko and Ian Roger Moore, for their love and support. To my sister, Lisa Moore, I thank her for her patience and good humor. Finally, my deepest gratitude goes to the women of the Sumire Kai who welcomed me into their lives and entrusted their stories with me.

Note to Reader

Japanese names are given in this book in the way they are used in Japan, with the family name first.

Macrons are used throughout to mark long vowels in Japanese, with the exception of well-known places such as Tokyo.

Monetary values are provided in yen. The exchange rate has fluctuated during the period in which the fieldwork for this book was conducted. For the purpose of comparison, however, in October 2013 one U.S. dollar was equivalent to 103 Japanese yen.

Introduction

One evening I attended a dinner party in a French restaurant in Tokyo. I sat next to a physician, Sakurai Fumiko, who talked enthusiastically about her passion for singing the operas of Franz Schubert. Fumiko had begun taking singing lessons in her mid-fifties in a private class. As she spoke of these lessons she seemed to be divulging a special dimension of herself that was still something of a secret but becoming an important part of the way she defined herself.

Fumiko introduced me to her friend Yamada Miki, who had just turned sixty-seven and had similarly begun a new learning pursuit when she had entered her late fifties. Mikis learning was tai chi. She began it, she claimed, to pave the way for her second life (dai ni no jinsei). Now, more than ten years into her tai chi passion, she was a licensed teacher of tai chi at a silver university in which the majority of her students were in their sixties and seventies.

As my circles of research contacts grew, I realized that Sakurai Fumiko and Yamada Miki were part of a vast and dynamic public culture of later life learning in Tokyo. I discovered that many women were immersing themselves in a diverse array of classes in which they pursued artistic activities, such as singing the operatic masterpieces of Franz Schubert, or studying the tea ceremony or flamenco dancing. While some pursued these activities in private one-on-one classes, more often than not these women, and also older men, practiced these activities in large groups where they learned and performed together. Many students were retirees or were expecting to enter retirement in the near future. My curiosity was piqued. What was this culture of learning about? Who were these students, many of them women, who poured their time, significant amounts of money, and physical and emotional energies into these classes?