Malanggan

MATERIALIZING CULTURE

Series Editors: Paul Gilroy, Michael Herzfeld and Danny Miller

Malanggan

Art, Memory and Sacrifice

SUSANNE KCHLER

First published 2002 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Susanne Kchler 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kchler, Susanne.

Malanggan : art, memory, and sacrifice / Susanne Kchler.

p. cm. -- (Materializing culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-85973-617-3 -- ISBN 1-85973-622-X (pbk.)

1. Ethnology--Papua New Guinea--New Ireland Province. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies--Papua New Guinea--New Ireland Province. 3. Art--Papua New Guinea--New Ireland Province. 4. New Ireland Province (Papua New Guinea)--Social life and customs. I. Title. II. Series.

GN671.N5K83 2002

305.8'09953--dc21

2002012010

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by JS Typesetting Ltd, Wellingborough, Northants.

ISBN 13: 978-1-8597-3622-7 (pbk)

To Josephine, Isabell and Ian

In Memory of Alfred Gell

This study has been a long time in the making. Thus the list of people to thank for help and encouragement along the way is potentially incredibly long: the Volkswagenwerk Research Foundation, which generously funded the first period of 20 months field-research in New Ireland; the Malinowski Research Fund, which helped in the final year of the Ph.D. at the London School of Economics and Political Science; and the Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, which funded a Postdoctoral Fellowship Year in 1989/90 and a Scholarship Year in Residence in 1995/96, during which most of this work was written.

My colleagues have never failed to inspire and encourage, but special thanks go out to Dieter Heintze, who first introduced me to matters malanggan, to Maurice Bloch, who encouraged me to pursue a Ph.D. at the LSE, to the late Alfred Gell, who instilled an awe for the English language and a passion for anthropology, and Marilyn Strathern, whose notes on my original thesis I still cherish. Of my colleagues who taught with me at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore between 1986 and 1990, I would like to thank Gillian Feeley-Harnik, whose work has been a lasting inspiration, Walter Melion, without whom my understanding of memory would not be the same, and Yves-Alain Bois and Michael Fried for their introduction into art history. At University College London I would like to thank Mike Rowlands for his understanding and patience during the many years of juggling teaching and child-care and all my students, in particular Sean Kingston, who helped me to keep going. The warmest thanks, however, go to Janet Hoskins-Valeri, who read an earlier draft of this work.

Special thanks go to all my friends in Lamusmus, Panamafei and Panachais villages, many of whom I can no longer thank. Nothing could have been accomplished without the organizational talent and enduring support of Francis in Panachais village and Saun in Panamafei village. They and countless others in Lamusmus 2, Panachais and Panamafei whose friendship was like a rock deserve thanks for waiting so long for this to return. I also want to thank my mother for her support, especially in the early days of this work, and Ian, Josephine and Isabell for their understanding.

At the centre of this study are objects known under the generic name of malanggan, which have come to epitomize the dilemma facing art in a disciplinary context that is riddled by the legacy of semiotics and the annihilation of analogy. Long misunderstood, malanggan have confounded all attempts at iconographic and contextual analysis. And yet, made as skin and as a likeness, of life, they make visible ideas that have come to inform recent rethinking of art and memory in terms of a theory of image and of agency. At once visually complex and yet superbly ordered, malanggan tell a story about how art can be thought-like, and, as a vehicle of thought, be the very stuff out of which life is wrought.

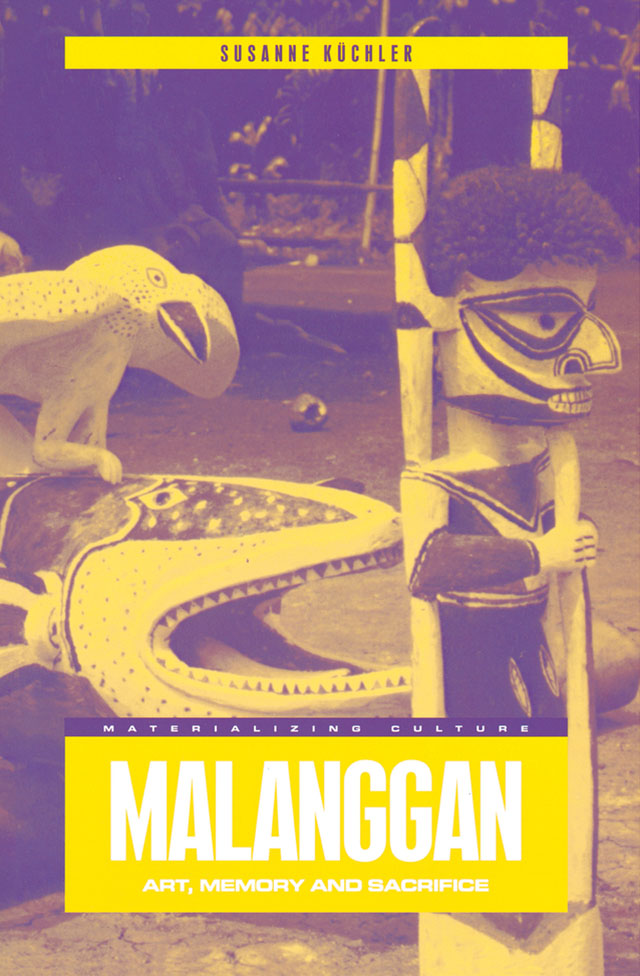

To this day, malanggan the funerary effigies used in New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, a ubiquitous collected item in ethnographic museums worldwide is the generic name of a funerary ritual that culminates in the production, revelation and death of effigies. When installed in a structure that is specifically erected for its display, the effigy is thought to be alive, having been gradually animated during the process of its production. Like the effigies of kings in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century England and France, which matched or even eclipsed the dead body itself, the effigy is attended as though the dummy were the living person himself being animated and subsequently allowed to die, thus allowing the deceased persons soul to achieve symbolic immortality. The height of the malanggan ceremony is the dramatic revelation of the effigy, followed moments later by the symbolic activation of its death. What took often more than three months to prepare is over in an hour, the empty remains of effigies being taken to the forest to be left to decompose or to the mission to be sold to collectors.

We have come to associate malanggan primarily with the figure itself. Carved from wood, it is enlivened as skin and is ultimately sacrificed, both effecting in its death the expelling of the dead person and initiating an exchange with the ancestral realm. The death of the object leaves behind a named and remembered image, which is recalled from time to time in states of reverie to re-direct ancestral power to the land of the living. The figure is thus an instance of a polity of images, whose access defines rank, authority and rights to land.

Visually and conceptually, the figure recalls a body wrapped in imagery. Incised to the point of breakage, the emerging fretwork is covered with depictions of birds, pigs, fish and seashells that appear almost lifelike; the same can be said for the figure set within the fretwork, which appears to stare at the beholder with eyes that could hardly be more vivid. It must surely have been the dreamlike quality of the animate surface of malanggan that inspired Surrealist artists to collect malanggan and draw upon them for inspiration for works such as Giacomettis Cage or Henry Moores sculpture entitled Upright Internal and External Forms (Brignoni 1995). Motifs appear enchained as figures stand inside the mouth of rock-cods, framed by many different kinds of fish that bite into limbs and chins, birds that bite into snakes and snakes into birds, and the skulls of pigs that appear to metamorphose into birds. Inner shapes appear enclosed by outer frames in ways that contest the apparent reality of what is depicted, like a vision in a dream. The figures give the impression of making connections visible as processes, but also visibly play with resemblance, as one figure appears to comment on another, being both similar and yet different.