Hollywoods Africa after 1994

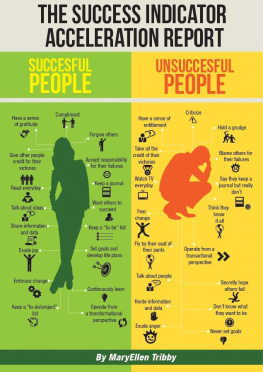

Edited by MaryEllen Higgins

Ohio University Press Athens

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

ohioswallow.com

2012 by Ohio University Press

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Cover art: Background photo, courtesy istockphoto.com; top: UH-60 Blackhawk,

courtesy Suzanne M. Jenkins, USAF; bottom left: Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg, Gauteng, on 13 May 1998, courtesy South Africa The Good News; bottom right: A miner in Kono District, Sierra Leone, searches his pan for diamonds, courtesy USAID Guinea.

Cover design by Beth Pratt

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hollywoods Africa after 1994 / edited by MaryEllen Higgins.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8214-2015-7 (pb : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8214-4433-7 (electronic)

1. AfricaIn motion pictures. 2. Human rights in motion pictures. 3. Imperialism in motion pictures. 4. Culture conflict in motion pictures. 5. Motion picturesUnited StatesHistory21st century. I. Higgins, MaryEllen, 1967

PN1995.9.A43H65 2012

791.43'651dc23

2012032543

Contents

Hollywoods Africa after 1994 i

Contents vi

Introduction 2

African Blood, Hollywoods Diamonds? 2

Chapter 1 The Cited and the Uncited 16

Chapter 2 The Troubled Terrain of Human Rights Films 36

Chapter 3 Hollywoods Representations of Human Rights 55

Chapter 4 Hollywoods Cowboy Humanitarianism in Black Hawk Down and Tears of the Sun 69

Chapter 5 Again, the Darkness 84

Chapter 6 Ambiguities and Paradoxes 97

Chapter 7 Minstrelsy and Mythic Appetites 111

Chapter 8 An Image of Africa 126

Chapter 9 Plus a Change, Plus Cest la Mme Chose 144

Chapter 10 New Jack African Cinema 158

Chapter 11 It Is a Very Rough Game, Almost as Rough

as Politics 179

Chapter 12 Every Brother Aint a Brother 195

Chapter 13 Coaxing the Beast Out of the Cage 209

Chapter 14 Situating Agency in Blood Diamond and Ezra 224

Chapter 15 Bye Bye Hollywood 242

Contributors 263

index 267

Introduction

African Blood, Hollywoods Diamonds?

Hollywoods Africa after 1994

maryellen higgins

At the conclusion of Edward Zwicks Blood Diamond, Ambassador Walker lectures an audience about the complicity of Westerners in the human crises fueled by conflict diamonds in Sierra Leone. The target audience for Walkers speech is not the actors playing attendees at the staged meeting in Kimberley, South Africa, of course, but rather the spectators watching the film. Walker announces:

The natural resources of a country are the sovereign property of its people. They are not ours to steal or exploit in the name of our comfort, our corporations, or our consumerism. The Third World is not a world apart, and the witness that you will hear today speaks on its behalf. Let us hear the voice of that world, let us learn from that voice, and let us ignore it no more.

Solomon Vandy, a humble Mende fisherman, approaches the podium. But before he utters his first word, the film ends, and the screen goes dark. In the films postscript, viewers are urged to insist that their diamonds are conflict free. Ironically, Solomons voice remains ignored as the film credits roll.

What are the messages conveyed in this moment? Does the severing of Solomons speech suggest that there is not yet an African (or Third World) perspectivethat there are no grassroots African authorities, no African humanitarians who can take the microphone and offer a new perspective? Or does Zwick implicate Hollywood itself, so that the framing of Solomons silence reads as a running commentary on Hollywoods perpetual denial of African agency? Are we expected to fill in the blankness of Solomons voice, rendering him an everlasting mute victim, unable to achieve liberation without our assistance?

We might also look at this scene in the context of another Hollywood blockbuster: King Solomons Mines, based on H. Rider Haggards best-selling 1885 novel, which has been adapted for movie and television screens on at least six occasions. King Solomons Mines epitomizes the imperial rationale: white adventurers arrive in Africa to locate hidden treasures that belonged to a biblical king, but also to save friendly, noble Africans from evil, monstrous tyrants. In 2006, Blood Diamond re-presents an African character named Solomon who reveals the location of a precious diamond in exchange for white protection against murderous African militants. In Zwicks reframing of the colonial narrative, Solomon is not an ancient king but a Mende fisherman, and diamonds are viewed not as glamorous jewels for the taking, but as catalysts for bloody conflicts linked to human rights abuses in Sierra Leones civil war. Zwick transmits a new cast of characters onto the African scene: greedy European corporate magnates, shady international arms dealers, and human rights advocates in the Kimberley Process initiative.

In recent films set in Africa starring Hollywood celebrities, human rights issues have become a major thrust. A close inspection of some of the most interesting new Africa films reveals a mixing of human rights concerns with familiar figures from what V. Y. Mudimbe describes as the colonial library (1994, 17), figures that have been revived and cleverly revised in a new century. The legendary David Livingstone, a nineteenth-century Scottish missionary doctor, is resuscitated cinematically in 2006 through the figure of Nicholas Garrigan, a Scottish doctor who loses his way during a mission to Uganda in Kevin Macdonalds thriller, The Last King of Scotland. There is a twist here, too. Previous Hollywood films tended to glorify Livingstones civilizing mission in Africa: the tagline of Henry King and Otto Browers 1939 Stanley and Livingstone reads, The most heroic exploit the world has known! Into the perilous wilderness of unknown Africa... Heat... fever... cannibals... jungle... nothing could stop him! In contrast, the Scottish protagonist in The Last King of Scotland befriends the tyrannical Ugandan president Idi Amin Dada, provides information that leads to the execution of Amins opponents, and fails to save anyone. Dr. Livingstones three Cscommerce, Christianity, and civilizationare replaced by Dr. Garrigans covetousness, corruption, and complicity.

This collection questions whether recent cinematic depictions of Africa adapt colonial fictions in order to subvert them, or whether they serve, ultimately, to reproduce colonialist ideologies. Crafted and reinforced by European and North American missionaries, travel writers, and filmmakers, colonial narratives consistently referenced Africa as a dangerous or exotic territory, as the pinnacle of horror and savagery, and as the recipient of the Wests benevolent, heroic humanitarianism. The argument here is not that all of the films examined in the volume fall neatly under the rubric of Hollywood cinema; instead, our focus is on the fate of what Kenneth Cameron calls the complex of received ideas about Africa that Hollywood has perpetuated (12). The chapters that follow examine big-budget, celebrity-studded films produced and distributed by major Hollywood studios but also independent films and transnational films that engage with Hollywoods Africa archives. When recent films set in Africa revisit narratives of empire, are they recycled reinforcements of an imperial enterprise, nostalgic renderings of the past, revisionist engagements, creative attempts at atonement, anti-imperialist subversions, distractions, a blend?