Media, Masculinities,

and the Machine

Media, Masculinities,

and the Machine

F1, Transformers, and Fantasizing

Technology at its Limits

Dan Fleming

and

Damion Sturm

The Continuum International Publishing Group

80 Maiden Lane, New York, NY 10038

The Tower Building, 11 York Road, London SE1 7NX

www.continuumbooks.com

2011 by Dan Fleming and Damion Sturm

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the permission of the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fleming, Dan.

Media, masculinities and the machine: F1, Transformers and fantasizing technology at its limits/Dan Fleming and Damion Sturm.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4411-1554-6 (hardcover: alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-4411-1554-4 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Mass mediaTechnological innovations. 2. Masculinity. 3. TechnologySocial aspects. 4. AutomobilesSocial aspects. 5. ToysSocial aspects. 6. Affect (Psychology) I. Sturm, Damion. II. Title.

P96.T42F57 2011

302.23dc

222010043691

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4411-5676-1

To love what aids fantasy, and so to gradually break down imaginative resistance...

Nigel Thrift

Contents

Acknowledgments

Our epigraph is from Nigel Thrifts Non-Representational Theory (2008, vii). were given as presentations or seminar papers at the University of Strasbourg in France, Halmstad University in Sweden, and at Aichi Shukutoku University in Nagoya, Japan, and have benefited from the constructive criticism received. Waikato graduate student Steven Hitchcock allowed us to use portions of his directed study project (Authoethnographies of Transformers) for which we are most grateful. Both authors wish to express a particular debt of gratitude to our students. Dan Fleming is grateful to the University of Waikato for the period of study leave during which the writing of this book was completed.

We would like to thank our editor Katie Gallof and copy-editor Molly Morrison for turning manuscript into book with such expedition and charm. This book is a project of Mediarena, a teaching and research facility at the University of Waikato that supports innovative approaches to studying and imagining the cultural impact of media and technologies.

List of Illustrations

Figure 4.1 The strategy intensity field.

Figure 5.1 The flow channel for optimal experience (Csikszentmihalyi 1992, 74).

Figure 5.2 The flow channel populated.

Figure 6.1 Adaptation of diffusion field to include a symbolic dimension.

Foreword

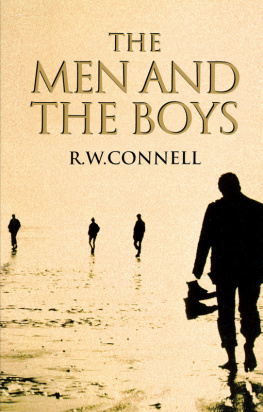

Masculinity is shaped in relation to an overall structure of power (the subordination of women to men), and in relation to a general symbolism of difference (the opposition of femininity and masculinity) (Connell 1995, 223). This book begins with a different but not unrelated premise: that today masculinity is also shaped in relation to another overall structure of powerthe subordination of technology to menand in relation to another general symbolism of differencethe opposition of human and machine. The interrelation of these structures and symbolisms constructs a complex matrix for contemporary masculinities to negotiate their way through. Indeed, it becomes more complex still with potential reversals of the power relations and interpenetration of the symbolisms. So just as The Atlantic magazine can run a cover story (July/August 2010) on The End of Men: How Women are Taking Control of Everything so too it becomes very easy to recognize everywhere the apparent subordination of men to technology (How Technology is Taking Control of Everything). And just as various types of new man celebrated by popular culture, such as the urban metrosexual with his groomed body image, suggest some feminizing of masculinity but more importantly a destabilization of the underpinning symbolic opposition, so the many cyborgs walking the popular media landscape suggest a symbolism of renegotiated or even collapsing difference between human and machine. What is a man to do?

In 2009 an English television presenterJames Maymade a six-part television series called Toy Stories that seems like one response to that question. The DVD cover calls it Ludicrously ambitious adventures and extraordinary feats of engineering using the worlds best-loved toys. James May was better known as copresenter of Top Gear, the astonishingly successfulslick and yet quirkily engagingBritish television show about cars that screens all over the world to huge viewing figures, with localized spin-off series on three continents. May is also a recognizable category of television presenter. To call this a type would be unfair, but he has discernible similarities with, for example, Jamie Hyneman and Adam Savage who present Mythbusters, originally a highly successful Discovery Channel asset and now also screened by numerous other television channels internationally (they use technology to test popular myths, such as bulletproofing a car with telephone directories). Although especially comfortable in these incarnations when playing with technology, this figure also occurs doing other practical things on television, as for instance British televisions Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall whose long-running River Cottage series documents his operation of a largely self-sufficient smallholding in rural England, or even somewhere in the background the fictional character Tim Taylor as played by Tim Allen in the 1990s American sitcom Home Improvement, although there it descended quickly into a reversible-screwdriver-celebrating, power-tool-wielding stereotype. More importantly, a Tim Taylor bespoke a moment when the mundane subordination of technology to men (and traditional family values as context) still seemed like a truth to many, whereas a James May inhabits a much more complicated world of reversible power relations and his response to it is considerably more knowing and ironic. Nonetheless, what all these manifestations share is that they are versions of an answer to Donna Haraways oft-ignored question in her seminal essay on the cyborg, What about mens access to daily competence, to knowing how to build things, to take them apart, to play? (1991, 181). Haraway was querying a credible feminist argument, making visible undervalued aspects of womens lives, that women have had a privileged claim over dailiness, the ordinary in everyday life. James May, however, makes the ordinary the very basis of his ludicrously ambitious adventures, which is quite possibly a very masculine talent to have.

The second episode of his Toy Stories series staged the worlds longest slot-car race at Englands old Brooklands racing circuit, the worlds first purpose-built motorsport track, not raced on since 1939 and now encroached upon by suburban sprawl. With the help of an enthusiastic local community of several hundred people, James May oversaw the construction of nearly 3 miles of Scalextric slot-car track (a nostalgia-inducing plaything dating back to the 1950s), over a river, through office buildings, around the overgrown remains of Brooklands banked section. Two little slot-car vehicles, chased by mobs of excited children, raced each other around the track, operated by local people in relays and given television coverage not unlike the real thing, with expert trackside commentary, onboard miniature cameras providing track-level views from the cars, accompanied by a carnivalesque atmosphere among spectators. In a bit of intertextual fun, a