copyright Julia Cooper, 2017

first edition

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Coach House Books also gratefully acknowledges the support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Cooper, Julia, 1985-, author

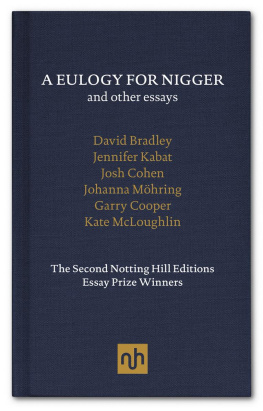

The last word : reviving the dying art of eulogy / Julia Cooper.

(Exploded views)

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978 1 77056 501 2 (EPUB).

1. Eulogies. 2. Eulogies--History and criticism. I. Title. II. Series: Exploded views

GT3390.c67 2017 393 c2017-900538-3

The Last Word is available in other formats: ISBN 978 1 55245 341 4 (softcover), ISBN 978 1 77056 502 9 (PDF).

Purchase of the print version of this book entitles you to a free digital copy. To claim your ebook of this title, please email with proof of purchase. (Coach House Books reserves the right to terminate the free download offer at any time.)

Prologue

L iving with the knowledge of death is harder than it sounds. To know its scent, its swiftness, is harder still. In Toni Morrisons 1973 novel Sula, a melancholic wwi veteran named Shadrack takes to the streets of his small Ohio town in a sombre, one-man parade celebrating an occasion of his own invention. Clanging a cowbell and clasping a hangmans rope, Shadrack marches to pay honour to suicide the ultimate act of taking control of ones death. Instead of allowing the spectre of his eventual end to grip him with fear, Morrisons glum soldier marks a single day in his calendar to function as an annual psychic release valve. He knows his anxieties around death are inescapable, and so he designates this day to reckon with and inhabit the gloom.

Shadracks DIY death parade points to a trenchant truth: if you want the space to ruminate on death, dying, and loss, youve got to sanction it yourself. No one else is going to eke out room for your grief. Learning to live with loss is an uncomfortable but necessary process, yet there exists so little space to talk about death and to grapple with prolonged mourning. Even at the few official moments we have carved out to directly address loss like the funeral eulogy there isnt much time to process, to grieve, to wallow before one is ushered toward the podium.

The eulogy is a particularly vexed art form, partly because its a necessity, and partly because at its very heart it is an amateurs art. It is no minor footnote that most Americans fear public speaking more than death itself; the eulogy is the fraught convergence of both, combining the speakers fear of death with that of public articulation, and layering the mess atop the experience of loss. As a consequence of our desire to distance ourselves from our fear, other matters often take precedence after a death. We have learned to push aside the emotional work of putting language to our loss. The calculations of inheritance, the listing of property, the distribution of stuff these are the things that make up the supposedly urgent work that follows a death. Less defined, less urgent, are the muddled feelings that loss occasions: etiquette ends up taking priority over the chaos of grief. As such, the eulogy often falls flat, backsliding into clichs that have sprouted around narratives of sorrow because we are seldom granted sufficient time and emotional space to craft meaningful last words.

Some narratives of grief have found new platforms, amplifying themselves through the collective megaphone of social media. These online tributes are typically just another socially sanctioned step in an all-too-efficient grieving process, one that even acts to speed up the pace of modern mourning. Virtual eulogizing is rapidly unleashed and hashtagged, but is quickly replaced with more timely, relevant news. Suffice to say, social media mourning beholden as it currently is to a sense of pseudo-professional productivity, and the gamified systems of likes, retweets, and shares is not precisely a radical new way to grieve in public.

Our online lives are only part of what Im interested in here, since the art of eulogizing has a much longer, and emotionally checkered, history. What this little book concerns itself with is the many and sundry iterations of the eulogy we find in cultural history, pop culture, literature, and philosophy, too. It turns out that whether youre an esteemed post-structuralist, a fictional widower in Love Actually, or Cher you will feel like a failure in the art of eulogizing. And its not because you didnt love fully, or even because the immensity of your grief has felled you, but because in a culture that sees death every day and yet hides the traces of grief that follow, there arent enough words for loss.

If the elegy is a poetic form that laments its dead in verse, and the obituary announces the hard fact of loss in the newspaper all the deaths that are fit to print then the eulogy falls somewhere in between. Intensely personal and yet meant to be spoken aloud to other grievers, the eulogy is a ritual that overlaps with the elegy and obituary in an invisible Venn diagram of funeral rites. The eulogy is often the first chance we have to gather publicly after a death, and its this charged moment where communities come together to puzzle over what a person meant to them when she was alive, and what she could mean now that she is dead. Does her story end in death, or is there a coda that extends even after the lights go out?

When Princess Diana died, her brother delivered a eulogy as the whole world, quite literally, watched. Buckling under the pressure of Dianas thorny kinship to the royal family, and likely under his own grief, the Earl of Spencer gave a eulogy so politically correct that it erased the flesh-and-blood woman behind the tiara. In some ways, he set the tone for how she would be remembered: as an icon that everyone wanted a piece of, but whom very few can now remember in much intimate or specific detail.

We have learned to structure our grief, however personal and inchoate, by marrying it to an invisible timeline that marches to a capitalist beat, two-stepping in time with pressures to be efficient, to progress, to most of all get back to work. The problem with such a regimented and overdeter-mined schedule is that, well, mourning doesnt work that way. There is no timeline because the work of grieving is never done. There is nothing efficient or productive about loss, but there it is all the same. Through the experience of grief, the heartbroken are uprooted from reality and planted into fantastical registers of the mind where time, results, and myths of progress dont abide. Its for this reason that, for me, grief has sometimes felt like my own personal Bermuda Triangle an imagined place that feels very real, a vortex that has vanished my loved ones, upended reality as Ive known it, and left me among the shoals to process my loss alone.

This book was written in the sombre but playful spirit of Shadrack. It is a reminder that you have to die. It is a reminder, too, that the anguish of losing is the basis of love. In the following pages I look to cinema, poetry, prose, song lyrics, and personal memory to find a bit more room for us to live with death, beyond the dictates of a calendar. I searched for eulogies that revived the dying art, because I still believe that attesting to a life in all of its contradictions and nuance is a confounding but loving task. Even the traumatized soldier of Morrisons