First published 2000 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an in forma business

William Washabaugh and Catherine Washabaugh 2000

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by JS Typesetting, Wellingborough, Northants.

ISBN 13: 978-1-859-73393-6 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-859-73398-1 (pbk)

We wish to express our appreciation for help, information and advice given by Al Anderson, Alan Brostoff, Jim Cheney, John Goulet, Dan OGrady, Laura Hewitt, Peggy Kell, Marti Kheel, John Kulczycki, Ron Manz, Jerry Merriman, David Monroe, Inky Moore, Scott Morgan, David Phelps, George Richard, Angela Shand, Chuck Schuster, Jim Washabaugh, Roger Widner, Bob Worth, and Brook Zem.

1

Fly-Fishing for

I was totally bamboozled; I was chicaned; I was necromanced (David Duncans Gus Orviston).

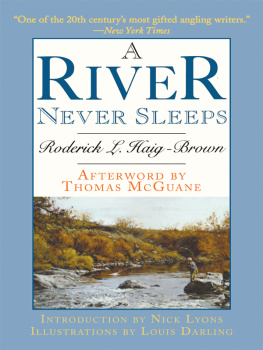

In again. Fly-fishing is in vogue. Angling is fashionable. Though not exactly hip, neither is it staid and stodgy. It has broken free from the old mold, and its ranks have swelled with new members. Its boosters, though still a small minority of outdoor buffs, have been enthusiastic and vocal, and their rhetoric has been ambitious, to be sure. It is no exaggeration to say that their vision is responsible for a new style, and a new way of life, one that some folks pursue day in and day out, in the home and office as well as in the streams and creeks. The cachet of this sport is difficult to summarize, though that is part of our mission here. However for starters, we can say that fly-fishing is appealing because it seems clean, bright, wholesome, and even noble. Fly-fishing is in because it bespeaks virtue and suggests authenticity. It is portrayed as a reality check, the antithesis of fakery, and the enemy of supercilious airs and social conceits. Fly-fishers are people who know where the center of the earth is.

None of this is particularly new. Angling has been called virtuous for centuries. Dame Juliana in the fifteenth century said it was good for the anglers soul: It shall cause hym to be holy. Izaak Walton, in the seventeenth, contended that God never did make a more calm, quiet, innocent recreation than Angling. In the eighteenth Charles Lamb recommended both angling and Waltons book to Coleridge, saying, It would Christianize every angry discordant passion. In our own times, we can read that the angler is privileged with an opportunity to become one with his soul and his God.

Trout-fishing has been touted as an especially noble activity, and the trout themselves have been portrayed as bearers of virtue, though any trout on any day would surely be willing to forgo all such honor and praise if it could just be let off the hook. In Waltons day, trout was a compliment that one might bestow on a person of noble bearing: I was a trusty trout/ In all that I went about (OED p. 2119). Today, the name of trout is just as enthusiastically revered amongst those who bend their knees on the banks of trout streams (Prosek 1999: ix). In other words, as we look from premodern England, to the postmodern United States, we can see similar inclinations to honor trout as if they were gods and to pursue fly-fishing as if it were a liturgy (L. Hemingway 1998: 15; Sutherland 1995: 1).

Walton celebrated trout with enthusiasm like our own. Perhaps the reason has something to do with the social turmoil that characterized his times just as it dominates ours. His world seemed all in pieces, all Cohaerence gone,/ All just supply and all Relation/ For every man alone thinkes he hath got/ To be a Phoenix and that there can bee/ None of that kinde, of which he is, but hee (John Donne 1611). Our world strikes many as identically cursed with all surface and no substance. Modern lives turn on markets, and spin, and cynicism. In these times, one is hard pressed to find simple joys and trustworthy experiences to embrace and pursue earnestly.

Since trout-fishing has been so often portrayed as a simple joy, it seems apt for our not-so-simple times. This is the line of thought that has been encouraged by the media throughout the twentieth century. Novels, essays, magazines, Hollywood and Madison-Avenue have all conspired to burnish the noble image of the evening angler, knee-deep in a stream curling its way through a well-forested valley, lazily casting his line to dimples in a pool. Early on, at the beginning of the century, Henry Van Dyke preached trout-fishing as the the best way of escape from this Taedium vitae (Van Dyke 1913: 14). More recently, at the centurys end, fly-fishing has been portrayed as a religious experience (Leeson 1994: 9; Madgic 1998: 108; Prosek 1999).

Before we move any further into discussions of taedium vitae or of the anglers haven from the heartless world, we should describe fly-fishing. A thumbnail sketch of typical angling practices will serve to root these discussions in concrete experience and will be especially helpful for those unfamiliar with the world that fly-fishers take for granted.

First, the object and focus of most fly-fishing is trout, specifically brown trout, rainbow trout, and brook trout, technically a charr, and kindred species. Other fish have always been taken, but trout, being beautiful, graceful, and wily, have long ranked first on the wish list of fly-fishers. These are aggressive, wary, carnivorous often cannibalistic fish that flourish in cold, clear streams. They favor two kinds of streams, free-stone streams, usually rushing brooks produced by run-offs from winter melts, or spring-fed streams, usually more demure. In both sorts, trout can be caught on flies that traditionally fall into four categories: dry flies, wet flies, nymphs, and terrestrials. Dry flies are fabricated in such a way as to rest on the surface of the water, therefore tempting trout that are rising or coming to the surface to feed on insects, especially mayflies, caddis flies, and stone flies as they emerge, lay eggs, or die there. Such imitations are fished on the waters surface: hence the name dry fly. Wet flies imitate emerging or dying insects below the surface of the water. Nymphs are tied in such a way as to imitate insects in their larval state. Terrestrials are tied in imitation of insects that live in the environs of streams and that are blown into the water, there to be taken by trout: for example, crickets, grasshoppers, ants, beetles. Additionally, flies can be tied to imitate other elements of the trouts diet: crayfish, scuds, eggs, etc.

A fly, being a bundle of feather and fur, is virtually weightless. In order to project it to where trout lie, the angler attaches it to a dozen feet of light tapered leader that is, in turn, attached to a heavy fly line. When the line is whipped backwards behind the angler with a backcast, it bends or loads the lithe light rod. Traditionally, this rod was a delicate instrument of lancewood or split bamboo todays price tag for a hand-made split-cane rod is around fifteen hundred dollars. But, advances in materials technology over the past thirty years, have made it possible to construct fiberglass or graphite rods seven to nine feet in length and as light as two ounces for mere hundreds of dollars. Whatever its material, the modern fly rod bends like a drawn bow as the angler executes the backcast. On the front cast, the rod launches the fly-line like an arrow, projecting it thirty to sixty feet, to the trouts lie, with fly in tow. Ideally, the fly settles itself onto the water quietly and gently as a feather falls onto a pillow. The angler allows it to move in the current of the stream as naturals do, and then, if it fails to attract a fish, retrieves it and re-casts the line.