WILLIAM LABOV

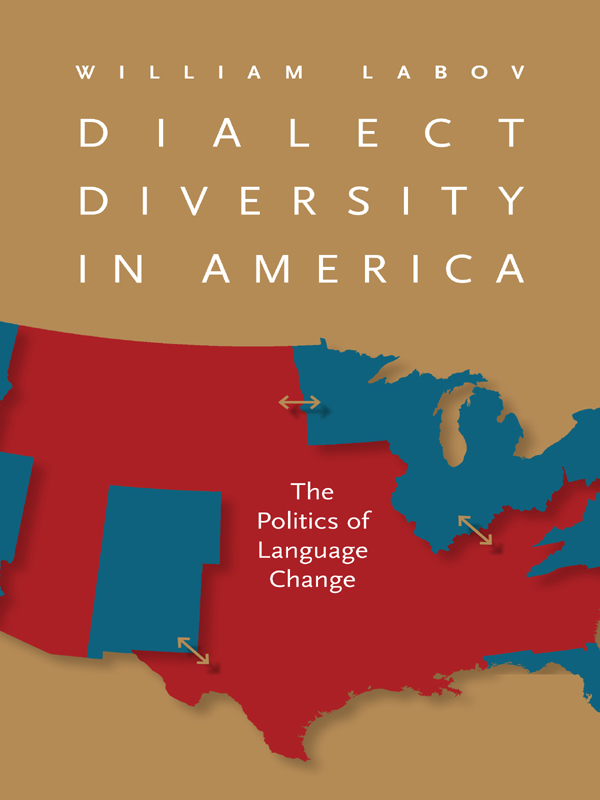

DIALECT DIVERSITY IN AMERICA

The Politics of Language Change

PAGE-BARBOUR LECTURES FOR 2009

University of Virginia Press Charlottesville and London

University of Virginia Press

2012 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2012

987654321

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

William Labov.

Dialect diversity in America : the politics of language change / William Labov.

p. cm. (Page-Barbour lectures)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8139-3326-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8139-3327-6 (e-book)

1. English languageDialectsUnited States. 2. English languageVariationUnited States. 3. English languageSocial aspectsUnited States. 4. English languagePolitical aspectsUnited States. 5. Linguistic changeUnited States. 6. African AmericansLanguages. 7. Black English. 8. Sociolinguistics. I. Title.

PE2841.L33 2012

427'973dc23

2012009828

Preface

When Eve Danziger invited me to give the 2009 Page-Barbour lectures, I was embarrassed as much as honored. I found that my predecessors in this series included those who had influenced me most deeply in the unlimited ambition of my early years. The list is so long that it would be claiming too much to name them here. But thinking of what I might say, I could only imagine an audience of these lecturers and of what I have to offer them. Now that my efforts to understand the world had focused on language and language change, how could I demonstrate that in the fifty years since I had read what they had to say, I had not wasted my time?

I was not worried about capturing the interest of the audience. Whenever I show that the dialects of American English are becoming more different from each other over time, the finding is so contrary to expectation that the audience demands an explanation. It is not only a challenge to our appreciation of the power of the mass media to control our behavior, but more profoundly, a challenge to our understanding of language as a means of communication. Even further, it puts into question our confidence in the rationality of human nature.

Any such accounting must also overcome the problem of communication between the linguist and the public at large. In no other form of human behavior is there such a great gap between reality and public discussion of it. Most of the sound changes I will discuss are inaudible and unknown to those affected by them. When language changes do rise to the level of social awareness, the stereotypes used to stigmatize them have only marginal relation to what is actually said in everyday speech. As a result, the field linguist interested in these changing patterns cannot focus overtly on the object of interest, since most people will reject the new forms once they become aware of them. In many areas of culture or technology, some older people will embrace and welcome the new. But in thousands of sociolinguistic interviews, no one has ever been heard to say, I really like the way that young people talk today; it's so much better than the way we talked when I was young. Most of us adhere to what one may call the Golden Age Syndrome: the belief that language once existed in a state of perfection, and any change is a decline from that state, to be resisted.

Much of the dialect diversity in America is the result of the growing divide between mainstream white dialects and African American Vernacular English (AAVE). Here the problem of communication is even deeper, and much of this book will be devoted to showing that the speech of African Americans is a coherent, well-formed, and different system, a fact obvious to all linguists but not at all to the general public. People who cannot detect a shred of racial bias in their own thinking will be profoundly biased in their reactions to African American speech. The ways in which race affects our views of language will intersect with our general effort to appreciate the role of rationality in linguistic matters.

I hope that my efforts to cross the gap between linguistic description and general literacy will lay the foundation for this effort to identify the driving forces in linguistic change. This foundation is only a first step, since the larger social forces plainly call for an interdisciplinary accounting. My own work on language stratification and language change is relevant to academic groups in fields beyond linguistics, as is evident from the fact that this invitation comes from a distinguished anthropologist. I have had fruitful interactions with many areas of psychology and sociology. These lectures reach out to historians and political scientists as well, areas in which my competence is more limited, even accidental. The word politics in the subtitle is indeed a central theme of the work, and we will see that the issues to be discussed are highly politicized. The argument will conclude with an effort to account for the striking coincidence between the Blue States of the 2004-8 elections and the major example of dialect divergence: the Northern Cities Shift.

Turning then to my imaginary audience of predecessors, I hope to persuade them that there is some profit in studying the instability of English, the means of communication that they used in their lectures, and that an explanation lies in the political nature of the animal that uses it.

Among my many intellectual debts that might be mentioned here, I will cite only one, to my colleague and wife, Gillian Sankoff, who has pondered these matters with me over three decades, and corrected innumerable errors of fact and logic in these lectures.

1

ABOUT LANGUAGE AND LANGUAGE CHANGE

This book is about language, about language change in particular, and especially about the changes that are now taking place in the dialects of North American English. It is also about the political causes and consequences of those changes. What is said here about language and linguistic change has a firm foundation in four decades of research on American English. On the other hand, I am not an expert in politics. For this area, I have drawn from the work of a wide range of historians, political scientists, and cultural geographers to make the necessary connections.

Some Commonsense Views of Language That Are Wrong

People tend to believe that dialect differences in American English are disappearing, especially given our exposure to a fairly uniform broadcast standard in the mass media. One can find this point of view in almost any discussion of American dialects, as for example in a recent exchange on Dr. Goodword's Language Blog. A contributor, Bruce, wrote:

The accents I do hear from people from around the country seem to be disappearing. People from New Orleans interviewed on TV or Radio seem to sound like me, as do many of those I hear from New York and elsewhere. I used to hear distinctive accents from people from Minnesota for example and those also seem to be going.

Dr. Goodword responded:

Bruce is absolutely right. Regional accents are dying outthe original dialects in this country were the results of the accents of the various immigrants who came to this country looking for a better life. They all landed on the east coast, which is why all the accents are currently in the east. However, as they migrated to the west, all these accents merged into one, so there are no distinctive regional dialects west or north of southern Ohio (maybe southern Illinois and a bit in northern Minnesota).

ABOUT LANGUAGE AND LANGUAGE CHANGE

ABOUT LANGUAGE AND LANGUAGE CHANGE