Contents

For my father, Frank David Riding (1956-2017),

forever remembered, never forgotten.

To my friends in Bosnia, and to the memory of Neil Golightly, 34, from Glasgow and Tony Richards, 46, from Godalming in Surrey, aid workers killed when their truck slipped over a cliff dodging gunfire on the final treacherous downhill stretch of the route into Sarajevo over Mount Igman on Monday 14 August 1995.

Those who live,

ache for death

to have meaning.

To be not so transparent,

but opaque with

impressively twisted

strands of sense.

When supersonic metal

slashes and carves, surely, we hope,

it must sculpt a beautiful purpose

and we will nod our heads wisely

and say Now we see.

Now we understand

why it had to be like this.

We did not know our destination

when we began this journey

but now we have arrived

and the effort

was worthwhile.

Could we cope

if grimy suspicion grabbed us

grubby with frontline dirt,

reaching from the soil

like a bony hand

partly skin-covered,

that death dont mean anything?

Stuart Laycock, Dont Mean

Preface

This book is an experiment in place-writing, a series of place-writing experiments undertaken over a period of five years. Its empirical focus is the Balkans, the former Yugoslavia, Bosnia, and Sarajevo, and it is concerned with the writing of these places after conflict. In very simplistic terms, the book aims to get at the heart of and to speak of post-conflict Bosnia, showing the past alongside the present it created. It does this by thinking through and meditating upon the journey to somewhere and conversely the stillness of being stuck somewhere. The juxtaposition between the siege of Sarajevo and supersonic metal, the refugee journey and the aid-worker travelling in the other direction, the desperation and fury to change the present yet being stuck with many of the ethno-nationalist politicians and politics of the past. It is a journey to somewhere, revealing how this point in place and time has been reached, a journey to and through post-conflict Bosnia, where I reach a square in Sarajevo and a specific point in place and time. It is a journey to a Bosnia as it is understood today in popular discourse, a war-torn place defined by ethnic conflict, yet a journey to deconstruct and reveal more than ancient ethnic hatreds portrayed on television screens across the globe from 1992 to 1995.

Here, through showing the past alongside the present through a series of stories in motion, while being still myself in a formerly besieged place, I hope to give over a sense of what Bosnia itself is like. On the one hand, it feels heavy with the weight of history, and yet on the other, it is an inspirational place with radical emancipatory politics. It is as such difficult to get at the heart of post-conflict Bosnia, given its fragmented landscape. Yet, I hope that here through the series of ethnographic journeys drawn upon, and through the retelling of memories of the past that I have at least given over of a sense of this place in words for those who have never been, and importantly for those who are from there. I have attempted to embed myself in the landscape, yet I can never truly understand, I can imagine but never truly experience, the past that I show here alongside the present.

The opening chapters work to introduce the region and the journeys undertaken, which are then expanded and drawn upon through a sustained attempt at exhausting a place, a square in Sarajevo. The reasons for writing of place here, and landscape, rather than through the usual geopolitical tropes of the state, become apparent over the following pages. It is not necessary to read the book in the order that it is presented in here, and indeed, it is possible to read the book backwards. Yet, for those with little knowledge of the region, chapter one provides a description of this project, and chapter two and three act as historical overviews of this place.

For those readers hoping to read a systematic analysis of the memorial landscape of Dayton Bosnia, this is not the book for them. In terms of memory studies, there are some gaps, for the reason that I am a geographer and I am interested in place, and how places are represented after conflict. I aim here through a series of experiential openings to provide a personal and performative reading of this place, beyond traditional geopolitical and Balkanist accounts, and to provide a reading, which also differs from memory and heritage studies. Indeed, there are what could be considered mistakes and generalisations here that will be noted by locals and scholars of this place. I recognise in writing this now, my own positionality as an outsider, which perhaps enables a different reading of this place, yet at the same time means some sentences may jar.

One such review noted that I overplay the phenomenon of Yugo-nostalgia, and I write that the memorials built to commemorate World War II in the former Yugoslavia, were all about mourning and not victory, and there are no monuments of warriors present in the landscape. In fact, many monuments are not abstract, and some of the most famous sculptors made many such memorials [of human forms]Radau, Baki, Augustiniincluding the iconic memorial of Stevan Filipovi raising his fists. There are also important studies by Lara Nettelfield on Srebrenica remembrance, many new books on socioeconomic issues, and importantly nostalgia (Velikonja, Boym, Todorova, Kolsto), which are important texts and I acknowledge here. While, as this text shares an interest in alternative forms of memorialisation with the Four Faces of Omarska project by Belgrade artist Milica Tomi, who is part of the collective Grupa Spomenik, creating interventions to challenge nationalist commemorative practices, I also again necessarily and importantly acknowledge that project here at the outset of this journey through post-conflict Bosnia.

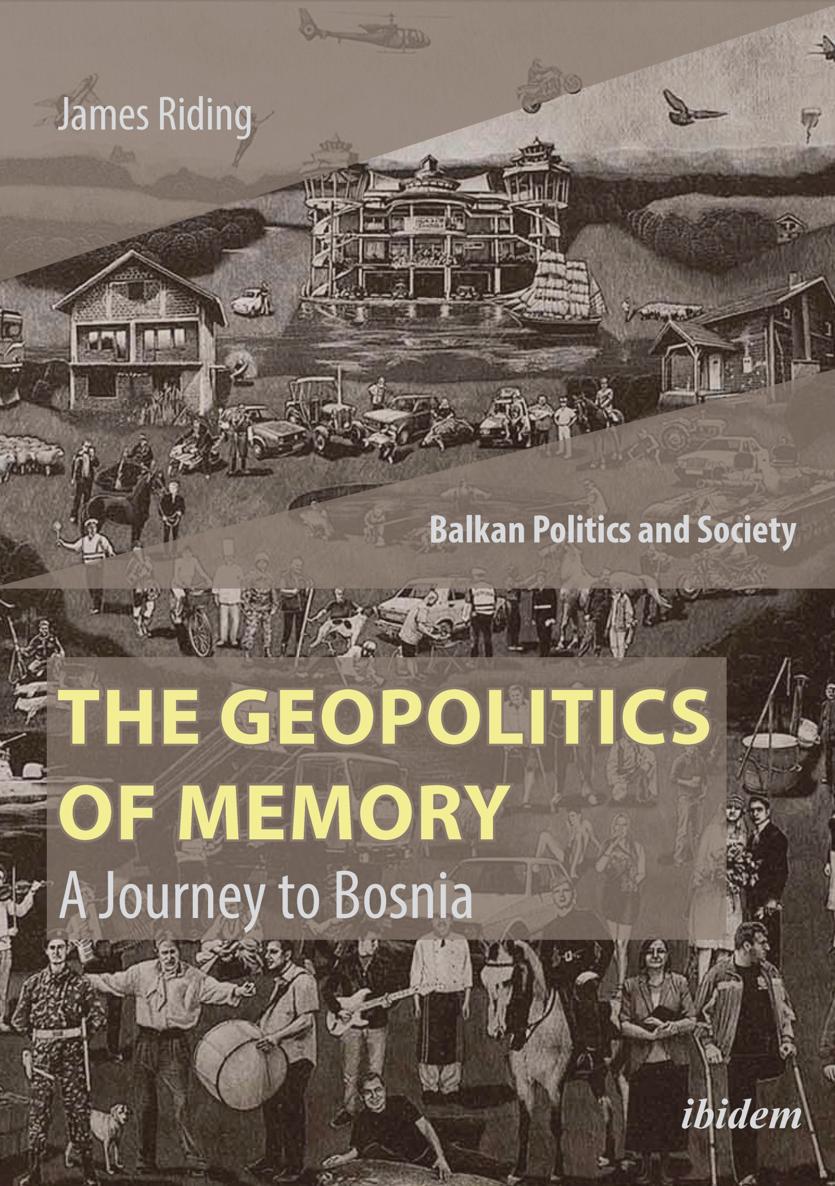

Speaking of art, I would here like to thank the artist Mladen Miljanovi for permitting the use of his work as a cover image for this book. I would also briefly like to say a few words about his work, which has influenced my own creative practice in post-conflict Bosnia. Born in Zenica, Yugoslavia, in 1981, Bosnian artist, Mladen Miljanovi completed secondary school in Doboj. After secondary school, he attended a reserve officer military school, where he earned the rank of sergeant. As a sergeant, he trained thirty privates. Following his military term, he enrolled at the Academy of Arts in Banja Luka, where he still lives. Wrought around an account of the divided place Miljanovis art is in and of, Bosnia-Herzegovina, in the remainder of this preface I trace a trajectory of an artists work, which exposes the largely concealed problematic geopolitical history of this small Eastern European country during a post-conflict, post-socialist, transition era (Horvat & tiks 2015). Amidst a fractured geopolitical landscape, Miljanovi has produced art with the aim of deconstructing ever-present ethnic and identitarian debates in Bosnia-Herzegovina, beginning with his own perceived identity (Campbell 1998). The experience of life growing up before and during the war in Bosnia, national service training as a soldier after school and living in a divided nation since were wound up into an epigraph: I Serve Art. There is in his work and the work of other artists in the first two decades of this century, working out of Banja Luka, the de facto capital of Republika Srpska, a clear intention to be a human rights activist and an artist, enfolding art and activism to produce a form of art activism. This is a radical and dangerous undertaking in a society still under the heavy influence of ethno-nationalist politics in the post-conflict, post-socialist, transition era, where a reduction or flattening of identity is a part of the state rhetoric.