For Ann, whose time was too short

And for Steve, who makes all the time better

Contents

My mother was always late. I vividly remember being the last kid picked up from birthday parties and waiting anxiously at airports for her yellow station wagon to appear around the corner. Running late with her was no less stressful. Speeding through traffic in a futile effort to make up for her late start, my father would be fuming behind the wheel, and my mother would be doing some last-minute task like mending the hem on her dress. Those minutes seemed like hours.

Time is subjective. Minutes spent waiting multiply; mundane tasks drag on. I recently timed how long it takes me to empty the dishwasher: 5 minutes. I had predicted it would take 15. Yet, blissful experiences, when were in the flow, seem to speed by. As Einstein observed: When a man sits with a pretty girl for an hour, it seems like a minute. But let him sit on a hot stove for a minute and its longer than any hour. Thats relativity.

My mother liked to fill time to the brim. It made her chronically late, but also incredibly industrious. It wasnt until I was an adult and met people from other countries and cultures that I realized not everyone operated on the edge of time. Some people think that less is more and allow ample time to get everywhere.

Time is confounding: It stands still. It flies. And it goes in cycles. There is no time like the present but tomorrow is another day. Ever since Einstein, we know that time (along with everything else) is relative. Poets wrestle with it, scientists measure it, and businesspeople try to lasso it into submission. And we all want to be reassureddont we?that we are not wasting the finite hours we have before us.

Americans generally feel time pressed. More than 1 out of 4 working adults say they dont have enough time to get done what they need to do, which makes them feel less satisfied with their lives and more stressed out. Meanwhile, the percentage of Americans who believe that science is making life change too quickly has been rising for the past five years.

The faster life becomes, the more we try to catch up with it. We want smarter phones, higher-performing computers, and faster food. We pride ourselves on multitasking and productivity. But then we flock to yoga and meditation classes, spin records the old-fashioned way, and cook slow food in an attempt to connect with the present moment. Its a constant struggle between our desire for instant gratification and our need for peace and reflection.

What to Expect?

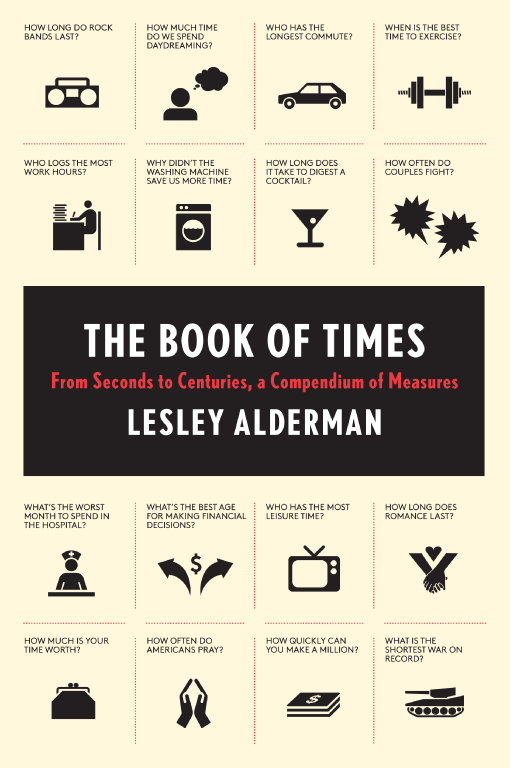

This is a book about how long things take, how long things last, and how much time we devote to a variety of activities. Why? Because objectively measured time is so surprising. How long does it take to build a bridge, write a symphony, or make a million dollars? Whats the optimal amount of time for making love? Whats the real time? And how are we spending the hours of each day?

The Book of Times is meant to amuse, inform, and provokethink of it as a quirky collection of facts with a slightly political edge. You may find yourself saying, Wow, who knew? or No way, this cant be possible! You may feel angered or even annoyed by facts or trends (thats the political part), and I hope you will find yourself questioning the way in which you spend your precious time each day.

Why a Book on Measured Time?

Perhaps because of my mothers peculiar attitude toward time, I have always been acutely aware of it. As a child I would write my schedule for the evening on a black chalkboard in my room: 6:00 P.M. homework, 7:00 P.M. call Karen, 7:30 P.M. Gilligans Island . You get the idea.

As I got older, I used time in an attempt to make order out of chaos. I timed how long it took me to get to the nearest subway stop, to read a page of a book, and to fold a pile of laundry. I even timed my romances: after three months of dating, if I was not in love, then it was time to move on.

The Book of Times sprang from my personal fascination with measured time and then morphed into something broadera collection of measurements of all sorts of things, from love affairs to school days, from the time we spend waiting to the time we spend learning. How many things can time measure? How many measures of time can be found? And what can those measures reveal?

Lucky for me, Americans love to gather data. The government measures the time we spend on all sorts of activities, as do polls, surveys, scientific studies, and academic research.

But just like time, data are relative. This book is chock-full of measurements, but not all measurements are created equal and not all measurements will stand the test of time. So I invite you to read on with an open, incisive, and questioning mind. And if you have gripes, suggestions, or corrections, please send me an e-mail: Lesley.Alderman@gmail.com.

Helpful Hints

The Book of Times is laid out in twelve chapters, like the twelve hours on the clock. Each chapter covers a single subjectlove, family, energy, and so onand contains dozens of timings. Youll also find suggestions on how to become more mindful of time through Time Exercises, quotes from great thinkers, and quizzes.

Before you begin reading, heres a quick refresher on some basic statistical terms and strategies that appear throughout the book. (If you have a math mind, skip ahead.)

When statisticians want to find the center of a set of data (commonly known as the average), they may measure the mean, median, or modeand sometimes all three.

Mean is interchangeable with the term average . To find the mean or the average of a data set, researchers tally up all the data and then divide by the total number of data points.

Median is the middle value of a list of numbers that are in a sequential order. Mean scores can be affected by outlier numbers at the edge of the data set, so when there is a set of numbers with extreme values, its often better to use the median to find the center of the set.

The mode is the value that occurs most often.

When researchers measure how people spend their time, they employ a few different strategies to get precise data. Lets say statisticians want to find out how much time Americans spend reading books: they could tally up the minutes every American admits to reading each day and provide a straight average, or they could tally up just the subset of Americans who actually read each day. The first average would include readers and nonreaders and be on the low side, while the second average would include just readers and provide a higher number. See the difference?

Statistics are tricky, and researchers often present the data in a light that supports their specific agenda or point of view. When I use data that might be skewedsay by the size of the sample, the date, or the authors point of viewIll say so. We are all mediators, translators, wrote the philosopher Jacques Derrida. Ive tried to get past perceptions and represent the best reality possible. Here, then, is my particular and carefully curated collection of timings.

How we spend our days, is, of course, how we spend our lives, the writer Annie Dillard observed. Broadly speaking, a day in the life of a typical American looks something like this: one-third spent sleeping, one-third spent working, and the remaining one-third spent on doing chores, making meals, eating meals, caring for kids and parents and pets, watching TV (a lot), socializing, and shopping. How people choose to spend those 8 hours of discretionary time varies tremendously depending on their age, gender, marital status, and more. The good news: leisure time has increased over the past four decades. The bad news: Americans dont feel like it has.