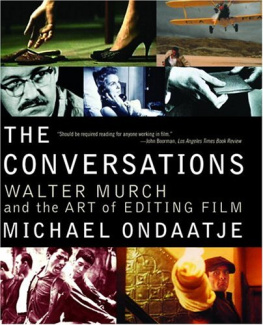

Walter Murch has been honored by both British and American Motion Picture Academies for his picture editing and sound mixing. In 1997, Murch received an unprecedented double Oscar for both film editing and sound mixing on The English Patient (1996, dir. A. Minghella), as well as the British Academy Award for best editing. Seventeen years earlier, he received an Oscar for best sound for Apocalypse Now (1979, dir. F. Coppola), as well as British and American Academy nominations for his picture editing on the same film. He also won a double British Academy Award for his film editing and sound mixing on The Conversation (1974, dir. F. Coppola), was nominated by both academies for best film editing for Julia (1977, dir. F. Zinnemann), and in 1991 received two Oscar nominations for Best Film Editing for the films Ghost (dir. J. Zucker) and The Godfather, Part III (dir. F. Coppola).

Among Murchs other picture editing credits are for The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988, dir. P. Kaufman), House of Cards (1993, dir. Michael Lessac), Romeo is Bleeding (1994, dir. P. Medak), First Knight (1995, dir. J. Zucker), and The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999, dir. A. Minghella)

Murch was the re-recording mixer for The Rainpeople (1969, dir. F. Coppola), THX-1138 (1971, dir. G. Lucas), The Godfather (1972, dir. F. Coppola), American Graffiti (1973, dir. G. Lucas), The Godfather, Part II (1974, dir. F. Coppola), and Crumb (1994, dir. T. Zweigoff), as well as all the recent films for which he has also been picture editor.

He has also been involved in film restoration, notably Orson Welles Touch of Evil (1998) and Francis Coppolas Apocalypse Now Redux (2001).

Screenplays on which Murch has collaborated include THX-1138, directed by George Lucas, and The Black Stallion (1979, uncredited), directed by Carroll Ballard. Murch directed and co-wrote the film Return to Oz, released by Disney in 1985.

Misdirection

Underlying these considerations is the central pre-occupation of a film editor, which should be to put himself/herself in place of the audience. What is the audience going to be thinking at any particular moment? Where are they going to be looking? What do you want them to think about? What do they need to think about? And, of course, what do you want them to feel? If you keep this in mind (and its the preoccupation of every magician), then you are a kind of magician. Not in the supernatural sense, just an everyday, working magician.

Houdinis job was to create a sense of wonder, and to do that he didnt want you to look here (to the right) because thats where he was undoing his chains, so he found a way to make you look there (to the left). He was misdirecting you, as magicians say. He was doing something that would cause ninety-nine percent of you to look over here when he wanted you to. And an editor can do that and does do that and should do that.

Sometimes, though, you can get caught up in the details and lose track of the overview. When that happens to me, it is usually because I have been looking at the image as the miniature it is in the editing room, rather than seeing it as the mural that it will become when projected in a theater. Something that will quickly restore the correct perspective is to imagine yourself very small, and the screen very large, and pretend that you are watching the finished film in a thousand-seat theater filled with people, and that the film is beyond the possibility of any further changes. If you still like what you see, it is probably okay. If not, you will now most likely have a better idea of how to correct the problem, whatever it is. One of the tricks I use to help me achieve this perspective is to cut out little paper dollsa man and a woman and put one on each side of the editing screen: The size of the dolls (a few inches high) is proportionately correct to make the screen seem as if it is thirty feet wide.

Seeing Around the dge of the Frame

The film editor is one of the few people working on the production of a film who does not know the exact conditions under which it was shot (or has the ability not to know) and who can at the same time have a tremendous influence on the film.

If you have been on and around the set most of the time, as the actors, the producer, director, cameraman, art director, etc., have been, you can get caught up in the sometimes bloody practicalities of gestation and delivery. And then when you see the dailies, you cant help, in your minds eye, seeing around the edge of the frameyou can imagine everything that was there, physically and emotionally, just beyond what was actually photographed.

We worked like hell to get that shot, it has to be in the film. You (the director, in this case) are convinced that what you got was what you wanted, but theres a possibility that you may to forcing yourself to see it that way because it cost so muchin money, time, angstto get it.

By the same token, there are occasions when you shoot something that you dislike, when everyone is in a bad mood, and you say under protest: All right, Ill do this, well get this one close-up, and then its a wrap. Later on, when you look at that take, all you can remember was the hateful moment it was shot, and so you may be blind to the potentials it might have in a different context.

The editor, on the other hand, should try to see only whats on the screen, as the audience will. Only in this way can the images be freed from the context of their creation. By focusing on the screen, the editor will, hopefully, use the moments that should be used, even if they may have been shot under duress, and reject moments that should be rejected, even though they cost a terrible amount of money and pain.

I guess Im urging the preservation of a certain kind of virginity. Dont unnecessarily allow yourself to be impregnated by the conditions of shooting. Try to keep up with whats going on but try to have as little specific knowledge of it as possible because, ultimately, the audience knows nothing about any of thisand you are the ombudsman for the audience.

The director, of course, is the person most familiar with all of the things that went on during the shoot, so he is the most burdened with this surplus, beyond-the-frame information. Between the end of shooting and before the first cut is finished, the very best thing that can happen to the director (and the film) is that he say goodbye to everyone and disappear for two weeks up to the mountains or down to the sea or out to Mars or somewhereand try to discharge this surplus.

Wherever he goes, he should try to think, as much as possible, about things that have absolutely nothing to do with the film. It is difficult, but it is necessary to create a barrier, a cellular wall between shooting and editing. Fred Zinnemann would go climbing in the Alps after the end of shooting, just to put himself in a potentially life-threatening situation where he had to be there , not day-dreaming about the films problems.

Then, after a few weeks, he would come down from the Alps, back to earth; he would sit down in a dark room, alone, the arc light would ignite, and he would watch his film. He would still be, inherently, brimming with those images from beyond the edge of the frame (a director will never be fully able to forget them), but if he had gone straight from shooting to editing, the confusion would be worse and he would have gotten the two different thought processes of shooting and editing irrevocably mixed up.

Do everything you can to help the director erect this barrier for himself so that when he first sees the film, he can say, All right, Im going to pretend that I had nothing to do with this film. It needs some work. What needs to be done?

Next page