To Those Who Count

To those who sample us randomly

and collect their numbers humbly

and confess how wrong they may be honestly

and report what they see whether it is

what they wished for or not

and share what they find with all of us

so we may learn something

we did not know of ourselves

CONTENTS

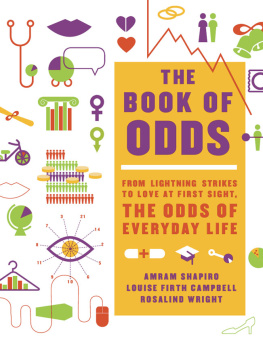

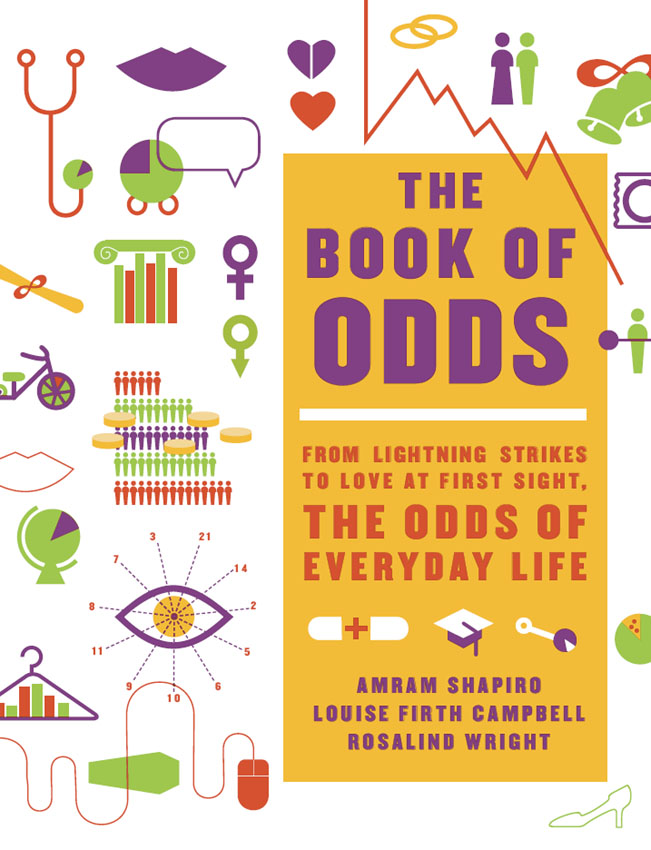

T his book is a numerical snapshot of the United States. Like a photograph its subject is stopped for a moment and set in context. It can be looked at so closely you can count the people in the bleachers and the buttons on their shirts. The photograph is not an Instagram but a panorama or 360-degree image. It addresses the destinies of people, from health and happiness to accidents and loss. It covers the cycle of life from conception to birth to childhood to schooling to adult life to aging and decline. It covers the everyday and holidays, the serious concerns of life and its comic turns.

What are the odds of that? We ask this when something strikes us as unlikely. We dont expect a reply since the question is rhetorical, an exclamation of surprise.

This book answers those questions in subject areas that tickle our curiosity or touch our anxieties and fears. Sometimes the odds surprise us. Sometimes they appall. Sometimes they amuse.

One thing the odds have in common in commonality. They are clear and simple. Every odds statement was created the same way and followed the same rules and conventions, the way entries in a dictionary do.

We look for the most fundamental units of activities or events to count, things just as we see them instead of more sophisticated, explanatory, but invisible measures. The likelihood of a batter hitting a single in a plate appearance is counted instead of his OPS (On-base Plus Slugging), or the odds a person owns blue jeans, rather than his propensity to spend.

Why? By concentrating on the experiences of normal existence, we have been able to develop a way of expressing the likelihood of these experiences. And we are able to compare likelihoods across a wide section of American lifesomething we call calibration . All of us already have an ability to calibrate, whether we recognize it or not. Think about how you automatically compare prices from one store to the nextyou not only have a grasp of what things should cost; you also have a sense of the reasonableness of a price. Or how about the morning weather forecast? Without thinking you know if a projected temperature suggests the need for a coat. You not only understand the number in context; you understand the implications it has for your daily life.

The odds in this book can help us calibrate all kinds of possibilities in the same kind of way. We can judge risk or likelihood in a way we have never been able to do before. For example, the odds are 1 in 8.0 a woman will receive a diagnosis of breast cancer in her lifetime, about the odds a person lives in California, the most populous state. And speaking of baseball, one story became iconic during the three years we were developing the Book of Odds database. In those days our researchers met weekly to review their work with one another. We often had visitors. On this day our visitor was a college student, the daughter of a close friend. The presentations she saw were really varied: one researcher had just completed work on the odds associated with contraception; another one had compiled the odds of baseball.

The odds of a woman becoming pregnant after relying on one form or other of contraception were displayed. Starting with the population of women in 2002 who were of child-bearing years (1544), the presentation identified the odds that one of these women was sexually active, the odds that she relied on condoms for contraception, and the odds that she would stop relying on condoms because she was pregnant. Each step of this thread of probabilities (as we term such chains) had independent odds. When put together, the odds that a woman in that original group would end up having given up condoms because there was no longer any pointshe had become pregnant despite the contraceptive measurewere 1 in 142 .

Next came the baseball presentation, and as it happened, our visitor was a baseball fan. She seemed captivated as the Book of Odds Major League Baseball statistics were summarized. They were different from those she was used to on the sports pages. What will happen next on average, independent of whos pitching and whos batting? Viewed this way, the odds that the next batter will hit a triple are 1 in 144 .

Later that day I received a call from my friend, the college students mother. Her daughter had returned home on a mission. She had immediately called her boyfriend, and her mother overheard her daughters part of the conversation. She asked her boyfriend if he knew the odds of a couple conceiving a child if they were relying solely on condoms, my friend said. She informed him that the odds were 1 in 142 .

Then she asked if he knew the odds of the next batter in a Major League Baseball game hitting a triple. Again, he didnt know.

Its 1 in 144 , she told him. And then she added, jabbing her finger for emphasis, And Ive seen triples.

We could go on and on: the odds a death will include HIV on the death certificate are becoming rarer and are 1 in 21,774

As I said, we could go on and on, which is why we wrote a book. Enjoy!

T his book is constructed on a considerable foundation. We began with a rigorous methodology, creating conventions and holding ourselves to the same standards as any reference source. Only then did we begin to assemble what has become a formidable database.

The very first database had only 450 odds but already vividly demonstrated how comparing disparate subjects with similar odds could both shock and inform. Take this example: The odds a female who is raped is under 12 are 1 in 3.4 . The odds a female rape victim is under 12 are about the same as a 99-year-old man dying in the next 12 months.

From there we went to work on growing the database and making it accessible for Internet use. We needed a way to classify the subjects we would cover and created a taxonomy that aided us later in employing semantic tools. More than fifty person-years went into creating more than 400,000 odds. Each one can be compared to any other, and thus each part enriches the whole.

But what do we mean when we talk about odds? When we say, My doctor says the odds are one in ten that the test will be positive, were expressing probability. In mathematical terms, statements like these put fractions into words. When we say, the odds are one in ten, think of a fraction, with the first, lower number as the numerator, or top number in the fraction, and the second, larger number as the denominator, or bottom number. So, one in ten literally means one-tenth, or a 10 percent chance. Each odds in The Book of Odds expresses the probability that a specific occurrence will take place, given the number of situations in which that occurrence might take place. Since it is past experience that provides a basis for expecting what will take place, odds are based entirely on past counts or on rare occasions actuarial forecasts.

Each statement in The Book of Odds contains certain required components. Consider the example, The odds a person will be struck by lightning in a year are 1 in 1,101,000 (US). First, we have to know what will happen, in this case, a lightning strike. Second, we have to know to whom it will happena person, any person. As we narrow that definition (a farmer, a golfer) the odds will change. Next, the statement tells us the parameters, or limitations, of the calculation. In this case, there are parameters of time (a single year), data span (annual data from 20082012), and of place (US). In this book all odds are US odds, so we have left the geography off and the data spans are usually evident in the sources cited. Any change to these parameters, as well as the time frame used to collect data, may change the odds. Some odds, such as those about the ideal fair coin toss coming up heads or tails, have no such parameters, and are considered true everywhere and any time because they are defined that way.