Introduction

It is extraordinarily difficult to avoid using grandiose adjectives in the description of ants.

Ants command a respect from their fans out of all proportion to the insects size. Ants, they affirm, are the -est insects: the cleverest, most organized, hardest-working, most numerous, most fecund, most dominant; they are older than humans, more bellicose, more cooperative, more communicative. Frequently these comparisons border on the bizarre. A childrens web site asserts: Ant brains are largest amongst insects... It has been estimated that an ants brain may have the same processing power as a Macintosh II computer.

At least, all this is what myrmecologists (those who study ants) would have us believe. Though their precise claims have changed over time, western students of ants always seem to have made hyperbolic assertions about them.

The eighteenth century natural philosopher Raumur started at a basic level in his catalogue of the extraordinary qualities of ants: we have for them none of those aversions that are frequently entertained towards so many other insects.This independent existence of ants has, at various times, been a source both of wonder and of horror. Thomas Mouffet, a sixteenth-century physician, noted that the ants

... are so exemplary... it is no wonder that Plato, Phaedone, hath determined that they who without the help of philosophy have lead a civill life by custom or from their own diligence, they had their souls from Ants, and when they die they are turned to ants again.

Here, the ants lack of reliance upon philosophy marks out the alternative yet equivalent nature of their civic lives: a parallel so wondrous that, according to Pliny, they are the only creatures besides us that bury their dead with funeral rites. More contemporary analogue-myths assert with equal confidence that ants, if magnified to the size of sheep, would rule the earth, and that in the event of a nuclear holocaust they would outlast humans.

In between the eras of Plato and NATO, observers have concocted a canon of astounding facts and figures concerning the numbers of ants, their distribution, their reproduction and modes of life. They are habitually scaled up to equate to human terms, upon which basis their nests are compared to the pyramids, or to the Great Wall of China, and their movement with that of a speeding train. They have recently been enumerated at ten thousand trillion; collectively they are asserted to weigh as much as the earths human population. E. O. Wilson, the most renowned living myrmecologist, claims that the behaviour of ants is scientifically more interesting than that of humans bestial cousin and the psychologists current favourite, the chimp. The reason for this, he writes, is that ants can be studied for the meaning of their social interaction, whereas the

The remainder of Ant explores this process of myth-making and suggests some reasons for the precise images and values that have been attached to ants at various times and in various places. The rest of this chapter, however, is devoted to a summary of the contemporary scientific understanding of ants: the stories that are told by myrmecologists today.

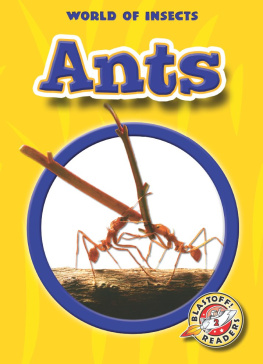

The animal kingdom is divided into successively smaller categories, which as they decrease in size reflect a greater degree of similarity and presumed evolutionary connection between their members. Phyla are the largest groups, which are then successively divided into classes, orders, families, genera, and finally into species. Insects are one class of the phylum Arthropoda. (Non-insectan arthropods include crustaceans and spiders.) The class Insecta is made up of various orders, including Coleoptera (beetles) and Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). The order Hymenoptera contains ants, as well as their evolutionary cousins, the bees and wasps. Termites, although often referred to as white ants have long been assigned to a different order, the Isoptera, which they share with their less loveable relations, cockroaches. Within the order Hymenoptera, one family Formicidae contains all the true ants. Ants are easy to recognize compared with many other insects. All are the same basic shape and have a characteristic kink in their ever-busy antennae. The Formicidae are split down into around three hundred genera, some of which have informal descriptive names such as sugar ants, bulldog ants or meat ants. Individual species vary in size between 0.7 millimetres and 3 centimetres in length.

At the time of writing, the latest count of ant species was 11,006. Although this represents a tiny proportion of knowninsect species (about 750,000, of which most are beetles), the combined weight of all living ants has been estimated to constitute half the mass of all extant insects. This figure, out of all proportion to the number of insect species, shows the success of ants in exploiting a variety of habitats around the world: just about everywhere apart from the polar regions.

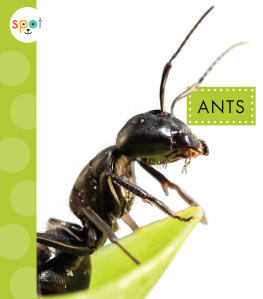

Frontal view of worker ant (Paratrechina sp.) showing the antennal kink characteristic of all modern ants.