The Reindeer People

by Megan Lindholm

Tillu & Kerlew Book 1

'Go deep,' he told the boy. 'Follow the little brown mouse when she takes her seeds and hides from the winter. Go to where the water bubbles up in a spring, and dive into its secret source. Follow the roots of the grandfather spruce down deep into the soil and beyond. This I tell you, for while every shaman must find his own entrance, these are ones that are known to have worked for some. Not all, but some. They are worth trying.'

Kerlew swallowed and tried to keep his drifting eyes on the old man's face. But Carp added another pinch of herbs to the lamp flame, renewing the wavering curtain of smoke between them. 'What do I seek?' Kerlew asked with difficulty.

Carp's tone was patient. 'I have told you. You seek for a magic, and a brother. Find a path into the spirit world and it will lead you to a deep room. The walls are of stone, and water drips down them. Roots hang from the ceiling. You must go through this room and out, into the spirit world. Do not speak to anyone in the stone room, not even if he calls you brother and offers you many fine gifts. For if you speak, you must remain there, and he will be free to take your place. Thus are many shamans trapped. I myself have seen them as I passed on my way to the spirit world. Don't speak to them!'

'I'm afraid,' the boy said suddenly.

The old man only shook his head, softening the gesture with a smile. 'You will go past those ones, and out into the spirit world. I cannot tell you what to expect, because for each shaman it is different. But when you meet your spirit guardian, you will know him. He may choose to test you. He may show you his teeth, or trample you beneath his hooves. He may rend you with his claws, or seize you in his talons and carry you up into the sky. Whatever he does, show no fear. Be bold, and set your palm between his eyes. Then he will be your brother, and he must give you a song or a magic to bring back with you. But if you cry out or flee or strive to hurt him, he will not be your brother. He will kill your spirit, and your body will waste away after you.'

Kerlew clenched his fists to keep his hands from trembling.

Carp saw, and for an instant the sternness of the instructor left his face. He looked down on his apprentice fondly. 'It will be all right,' the old man said kindly. 'Go ahead, now. Don't be afraid.' He touched the boy's cheek with his weathered old hand, dragged his fingertips across Kerlew's lined brow to soothe away the worry wrinkles.

'You will be a great shaman, and all will point and tell tales about Carp's apprentice.'

The boy gave a brief nod and tried to swallow the anxiety that started in his stomach but kept trying to squeeze up his throat. Old Carp smiled at him reassuringly, his pride and belief lighting his seamed old face. His teeth were yellow, separated by black and empty gaps. Kerlew thought his eyes must have been brown once. Now they were skimmed with gray film that reminded him of the green slime that clouded the surface of summer ponds. Kerlew knew that if one stirred the slime with a stick, the depths and wonders of the pond beneath it were revealed. Sometimes when he stared at Carp's clouded eyes, he thought he glimpsed the depths and wonders beyond the gray that misted them. Gray as the smoke that drifted and wandered through the tent. When he breathed it in, it was like breathing cobwebs. It clung to the inside of his nose and lined his throat with dryness.

Carp's withered lips were moving, and Kerlew focused on them with difficulty. He was supposed to be listening, he remembered belatedly. The smoke was supposed to make this easier. Instead it was making it harder.

'Just breathe deeply and listen to the drum. Let the drum guide you. Listen now.'

The drum. Kerlew shifted his eyes to Carp's hands. A little drum with a yellow-leather drumhead was gripped between the old man's knees. In one of Carp's hands was a tiny hammer, made from a bear's molar mounted on a stem of birch. Kerlew watched the molar lift and fall, lift and fall, lift and fall. Each time it struck the taut leather it made a sound. Listen to it. He was supposed to listen to it. The old shaman's fingers were the same color as leather that had been used a lot and hung up inside a smoky tent. Like this smoky tent. His eyes drifted away from the drum and fingers, rose to follow the gray smoke as it swirled silently through the tent.

Carp was still talking to him. His words drifted through the tent with the smoke.

'Listen to the drum and let go of this world. Breathe in in this world, breathe out in the spirit world. Let go and go down, into the spirit world to seek out your spirit beast. Go down, follow a mouse, follow a beetle, go down into the spirit world, followatrickleofwatergodown- deepintotheearth ...'

The words mingled with the smoke and swirled through the tent and up. Up and around, past the patch sewn on the tent wall, past his leggings hung to dry on one of the tent supports, past the old shaman's head. Kerlew lay still on his pallet of hides and watched them. His tongue was gummed to the roof of his mouth and he could not let out his breath. He could take in air, and he felt his chest swell tighter with every breath.

But he couldn't let the air out. For a slow moment he noticed this and it troubled him.

Then his attention was caught once more by the swirling smoke. He watched it glide, so gray and soft and free. He let out a long sigh and followed the smoke.

Once he had fallen into a river, and before his mother could snatch him out, he had been washed downstream on the buffeting flood. This was like that time, except the smoke was warm and soft and there were no great stones to batter him. It carried him up and around, toward the peak of the tent and the smoke hole. He brushed past the old shaman's bent head, heard a few lingering notes from the skin drum. For that instant he remembered that he was supposed to be going down, into the earth to seek the depths of the spirit world. Then he swirled past Carp and was carried aloft on the smoke. The old shaman's instructions no longer seemed important. He floated up and out of the smoke hole.

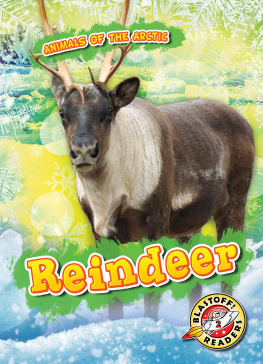

The night was black, studded with stars. Winter was but a breath away, yet Kerlew did not feel the cold. He hunted across the sky, the smoke soft beneath him, his every stride a stag's leap. Then, as he felt the smoke grow thinner and fade, he began to step from star to star just as one could step from stone to stone in a stream crossing, or from hummock to hummock in a bog. Gone was his usual clumsiness and halting stride.

Here he walked as a hunter and a man. The night wind touched his hair.

Higher and higher into the sky he climbed, until far ahead of him he saw the pale hides of the moon's caribou. Far above the stars behind the moon, the herd was scattered out across the black sky. Kerlew stood on the highest stars and lusted after them. Their coats shone like lake ice and their antlers swept white and gleaming over their backs. Their heads were down and they grazed across the night sky. He knew that the smoke of their breath formed the clouds, and the clash of their antlers presaged thunder and lightning. Their power and majesty made his heart ache. He knew that if he touched one between the eyes and claimed it as his spirit brother, he would be a powerful shaman indeed.

But between him and the herd the stars were few and widely scattered. He stood teetering atop two stars, yearning after the sky caribou, and wondering what he should do. Briefly he recalled that Carp had told him to go down into the earth, not up into the sky. With a sinking heart, he knew he had disobeyed his master; he would fail in his hunt. He would return from this journey, no shaman, but only the healer's strange boy.