Contents

Guide

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright Laura Galloway, 2021

The moral right of Laura Galloway to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Portions of this book appeared previously in Intelligent Life magazine

The Law of Jante excerpt on is taken from A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks by Aksel Sandemose (A.A. Knopf, 1936)

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 91163 067 8

E-Book ISBN 978 1 76087 325 7

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jonathan

AUTHORS NOTE

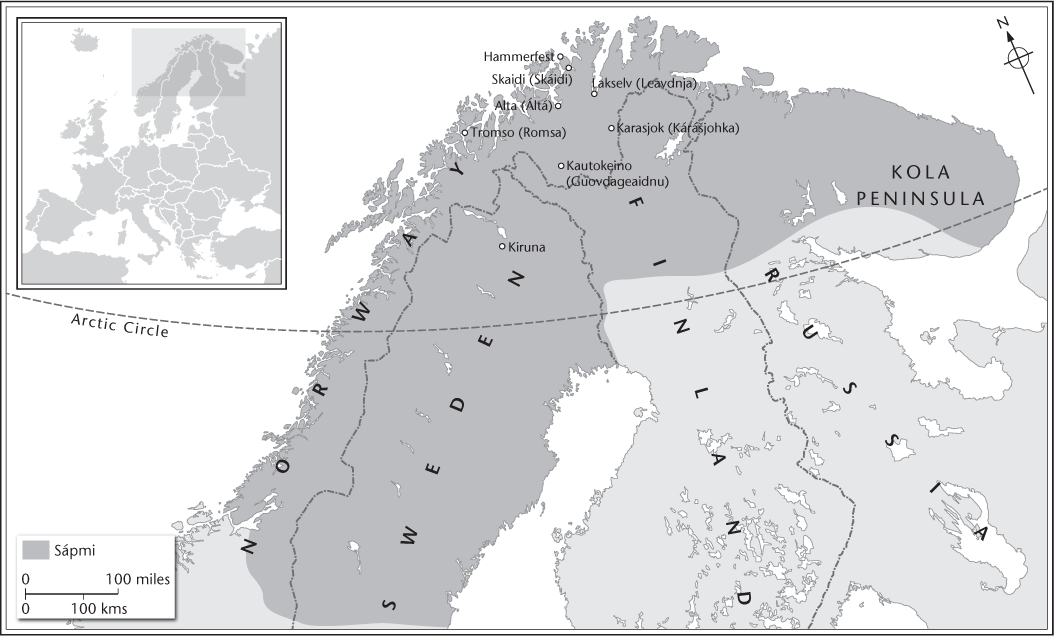

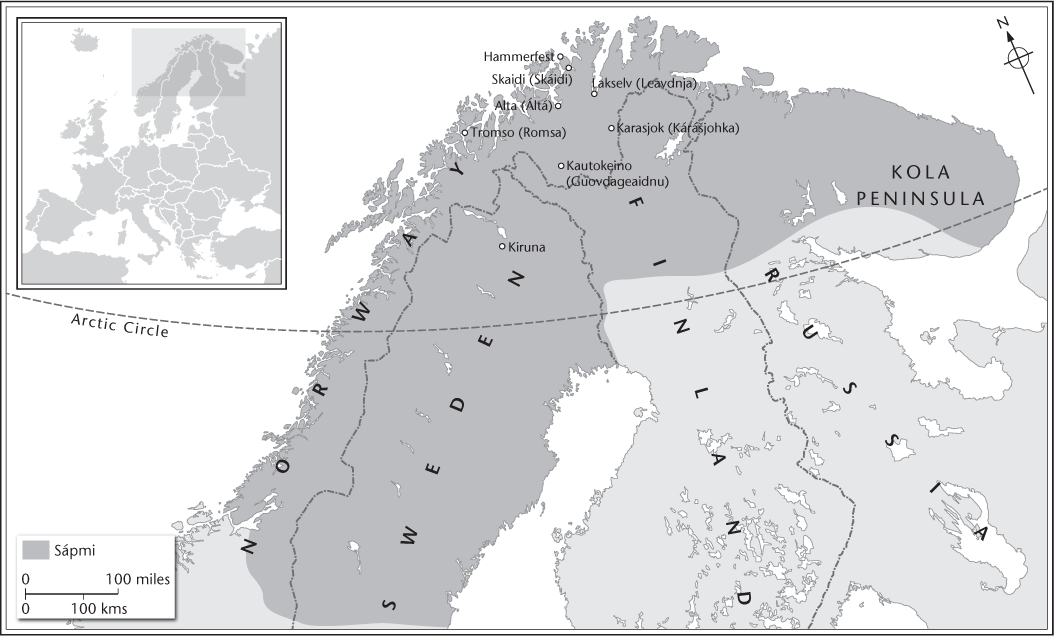

Many, but not all, of the names and some key identifying details of the central individuals about whom I write in this book have been changed in the interest of privacy and anonymity. There are no fictional or composite people or events. Dlvi is based on many years of notes, diaries, letters and my memories and recollections. In the editing process, I have tried my best to respect Smi culture by employing a Smi reader for checking of key facts, spellings and impressions, yet it cannot be underscored enough that Dlvi is singularly a product of my urban, outsider lens and experiences in this particular culture, rather than an insiders view or perspective.

INTRODUCTION

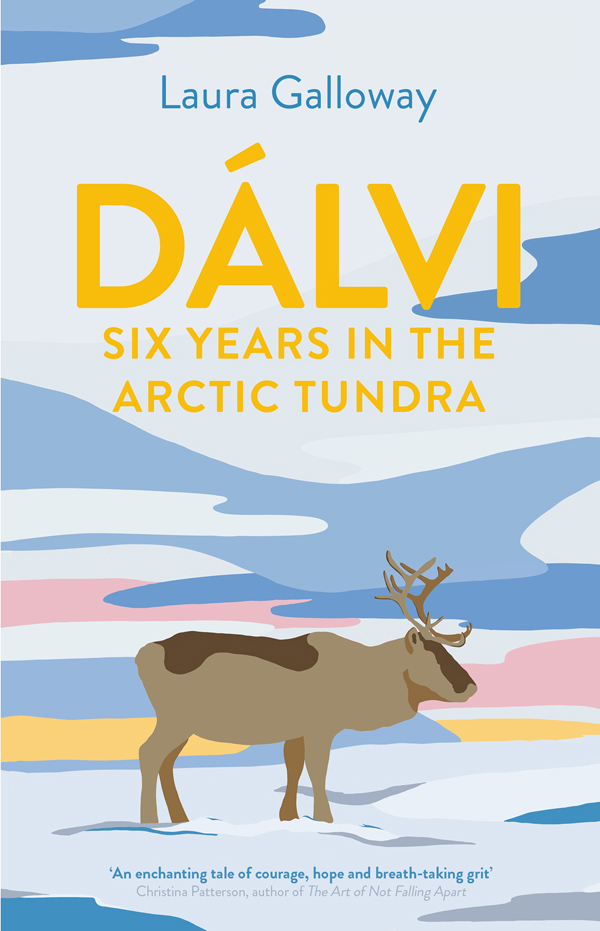

I t is minus fifteen Fahrenheit the first time I arrive in the Arctic, in dlvi, the Northern Smi word for winter. A giant LCD screen at Swedens Kiruna airport displays the temperature. As I step off the plane, it is not the snow or the cold or the bleakness that gives me pause. It is the utter silence, muffling even the idling jet engine of the plane. My cheeks bloom red from the brittle cold as I wait for a taxi next to a sign indicating a parking spot for sled dogs. This is the farthest place imaginable from my home in New York, in both temperature and ambience.

The air is completely still and lead-like with the cold, as if words might shatter if spoken. As we drive through the night to my hotel, Im oblivious to the towering Scots pines and Norwegian spruce that dot the forlorn roadsides and would appear with the golden pink light of morning, laden with layers and layers of snow, creating towering sculptures of spun candyfloss. The beauty is singular, and it is also deceptive; this is, too, a place of dark and endless nights, of bitter cold and of survival.

The Arctic north in winter is a great void, which is perhaps why I am so drawn to it. In its nothingness, there is no chaos, no ambiguity; there is nothing to be done except to be there, swallowed by the enormousness of ones surroundings, a bleakness which can either foster a sense of retreat or inspire possibility, depending on your state of mind and what you need most at that moment.

I am filled with the sense of aloneness that has travelled with me longer than I can remember, which is a part of me. But in the sting of the cold, I also feel something foreign and unfamiliar, and which I thought had been lost to me long ago: a sense of wonder.

1

UNRAVELLED

F reezing cold and tired, I am holding on to a long green tarp, alongside a handful of others, guiding reindeer into an enormous holding enclosure in a remote part of the Norwegian Arctic. A giant buttery moon lies flat against the hard blue twilight sky, so low you feel as if you could easily touch it. It illuminates everything: from the jumpy reindeer moving en masse, a blinding flurry of hooves and poop and antlers, to my warm breath hitting the rimy cold night sky in plumes like a smoker with a phantom cigarette. As I look up at the moon, toes numb in my muddy boots from having stood for what feels like hours waiting for the herders to bring the reindeer in from the tundra, I am struck by the absolute insanity and marvel of life, and of the improbable twists and turns in our stories that we could never begin to imagine.

One year ago, a Saturday night would not have involved standing on the frozen expanse of the Finnmark plateau with a family of Smi herders, watching steaming blood being scooped out of a reindeer carcass as its field-dressed by a grunting Smi man named Odd H tta with a giant knife. One year ago, I would have been walking through Union Square in New York on my way to a progressively boozy dinner with friends, spending hours talking about their work and my media job, and did you read such and such in the New Yorker, and what show was on at MoMA or what was happening in the increasingly worrying political landscape. And, of course, there would have been talk of relationship problems and there were always problems or money problems and how busy everyone was. And then the evening would have slowly unravelled, everyone growing louder and more maudlin, until it was over, faded into a history of Saturdays just like every other one that came before it, followed by a sharp hangover the next day, a raft of emails and stress and worries about everything back in full view in an endless cycle.

Those days were now far behind me, a distant memory of the person I was, tucked away like the dozens of utterly useless high-heeled shoes that sat with all my other earthly possessions in a storage area some two thousand miles away in Manhattan, collecting dust and losing relevance. In my old life, tomorrow I would be heading to City Bakery for an iced coffee, with crippling anxiety about the Monday to come and how I would hang on one more day in a life that was becoming unmanageable to an extent of which no one around me was really aware, unless you happened to be the lucky recipient of a spectacular late-night Laura Galloway Ambien and red-wine phone call.

I was breaking open and falling apart, and to reveal this weakness and vulnerability to anyone might have caused me to die of shame. But the universe seemed to have plans for me, ones that would take me outside of everything I knew, and everything that I thought made me me, to a place where I now think nothing of not showering for three days straight, and Saturday involves helping chop wood for a fence-post, or cutting reeds to dry and braid into shoes for the brittle winter to come, or smoking reindeer meat in a tent called a lvvu while drinking bitter black coffee, the smoke clinging to my hair and clothing and settling into my pores. This is a place where you have to be with yourself because there are no distractions. Only work and nature and time.