Bitterblue

(Graceling Realm, #3)

by Kristin Cashore

This one was always for Dorothy

WHEN HE GRABS Mama's wrist and yanks her toward the wallhanging like that, it must hurt. Mama doesn't cry out. She tries to hide her pain from him, but she looks back at me, and in her face, she shows me everything she feels. If Father knows she's in pain and is showing me, Father will take Mama's pain away and replace it with something else.

He will say to Mama, "Darling, nothing's wrong. It doesn't hurt, you're not frightened," and in Mama's face I'll see her doubt, the beginnings of her confusion. He'll say, "Look at our beautiful child. Look at this beautiful room. How happy we are. Nothing is wrong. Come with me, darling." Mama will stare back at him, puzzled, and then she'll look at me, her beautiful child in this beautiful room, and her eyes will go smooth and empty, and she'll smile at how happy we are. I'll smile too, because my mind is no stronger than Mama's. I'll say, "Have fun! Come back soon!" Then Father will produce the keys that open the door behind the hanging and Mama will glide through. Thiel, tall, troubled, bewildered in the middle of the room, will bolt in after her, and Father will follow.

When the lock slides home behind them, I'll stand there trying to remember what I was doing before all of this happened. Before Thiel, father's foremost adviser, came into Mama's rooms looking for Father. Before Thiel, holding his hands so tight at his sides that they shook, tried to tell Father something that made Father angry, so that Father stood up from the table, his papers scattering, his pen dropping, and said, "Thiel, you're a fool who cannot make sensical decisions. Come with us now. I'll show you what happens when you think for yourself." And then crossed to the sofa and grabbed Mama's wrist so fast that Mama gasped and dropped her embroidery, but did not cry out.

"Come back soon!" I say cheerily as the hidden door closes behind them.

I REMAIN, STARING into the sad eyes of the blue horse in the hanging. Snow gusts at the windows. I'm trying to remember what I was doing before everyone went away.

What just happened? Why can't I remember what just happened? Why do I feel so

Numbers.

Mama says that when I'm confused or can't remember, I must do arithmetic, because numbers are an anchor. She's written out problems for me so that I have them at these moments. They're here next to the papers Father has been writing in his funny, loopy script.

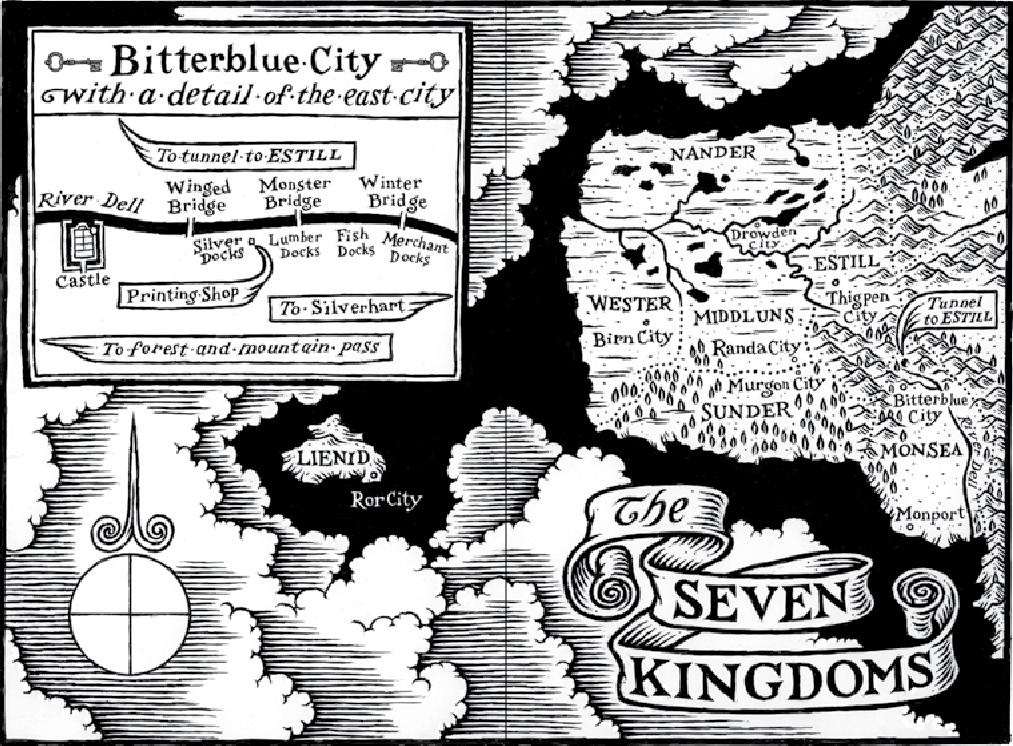

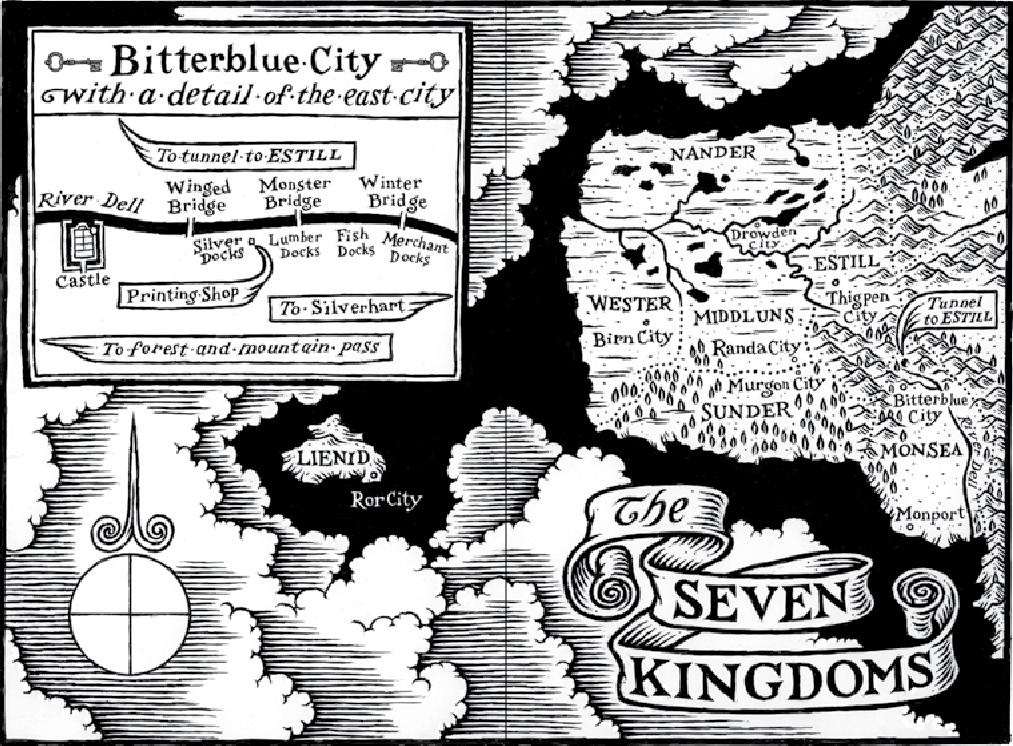

46 into 1058.

I could work it out on paper in two seconds, but Mama always tells me to work it out in my head. "Clear your mind of everything but the numbers," she says. "Pretend you're alone with the numbers in an empty room." She's taught me shortcuts. For example, 46 is almost 50, and 1058 is only a little more than 1000. 50 goes into 1000 exactly 20 times. I start there and work with what's left. A minute later, I've figured out that 46 into 1058 is 23. I do another one. 75 into 2850 is 38. Another. 32 into 1600 is 50. Oh! These are good numbers Mama has chosen. They touch my memory and build a story, for fifty is Father's age and thirty-two is Mama's. They've been married for fourteen years and I am nine and a half. Mama was a Lienid princess. Father visited the island kingdom of Lienid and chose her when she was only eighteen. He brought her here and she's never been back. She misses home, her father, her brothers and sisters, her brother Ror the king. She talks sometimes of sending me there, where I will be safe, and I cover her mouth and wrap a hand in her scarves and pull myself against her because I will not leave her.

Am I not safe here?

The numbers and the story are clearing my head, and it feels like I'm falling. Breathe.

Father is the King of Monsea. No one knows he has the two different colored eyes of a Graceling; no one wonders, for his is a terrible Grace hidden beneath his eye patch: When he speaks, his words fog people's minds so that they'll believe everything he says. Usually, he lies. This is why, as I sit here now, the numbers are clear but other things in my mind are muddled. Father has just been lying.

Now I understand why I'm in this room alone. Father has taken Mama and Thiel down to his own chambers and is doing something awful to Thiel so that Thiel will learn to be obedient and will not come to Father again with announcements that make Father angry. What the awful thing is, I don't know. Father never shows me the things he does, and Mama never remembers enough to tell me. She's forbidden me to try to follow Father down there, ever. She says that when I am thinking of following Father downstairs, I must forget about it and do more numbers. She says that if I disobey, she'll send me away to Lienid.

I try. I really do. But I can't make myself alone with the numbers in an empty room, and suddenly I'm screaming.

The next thing I know, I'm throwing Father's papers into the fire. Running back to the table, gathering them in armfuls, tripping across the rug, throwing them on the flames, screaming as I watch Father's strange, beautiful writing disappear. Screaming it out of existence. I trip over Mama's embroidery, her sheets with their cheerful little rows of embroidered stars, moons, castles; cheerful, colorful flowers and keys and candles. I hate the embroidery. It's a lie of happiness that Father convinces her is true. I drag it to the fire.

When Father comes bursting through the hidden door I'm still standing there screaming my head off and the air is putrid, full of the stinky smoke of silk. A bit of carpet is burning. He stamps it out. He grabs my shoulders, then shakes me so hard that I bite my own tongue. "Bitterblue," he says, actually frightened. "Have you gone mad? You could suffocate in a room like this!"

"I hate you!" I yell, and spit blood into his face. He does the strangest thing: His single eye lights up and he starts to laugh.

"You don't hate me," he says. "You love me and I love you."

"I hate you," I say, but I'm doubting it now, I'm confused. His arms enfold me in a hug.

"You love me," he says. "You're my wonderful, strong darling, and you'll be queen someday. Wouldn't you like to be queen?"

I'm hugging Father, who is kneeling on the floor before me in a smoky room, so big, so comforting. Father is warm and nice to hug, though his shirt smells funny, like something sweet and rotten. "Queen of all Monsea?" I say in wonderment. The words are thick in my mouth. My tongue hurts. I don't remember why.

"You'll be queen someday," Father says. "I'll teach you all the important things, for we must prepare you. You'll have to work hard, my Bitterblue. You don't have all my advantages. But I'll mold you, yes?"

"Yes, Father."

"And you must never, ever disobey me. The next time you destroy my papers, Bitterblue, I'll cut off one of your mother's fingers."

This confuses me. "What? Father! You mustn't!"

"The time after that," Father says, "I'll hand you the knife and you'll cut off one of her fingers."

Falling again. I'm alone in the sky with the words Father just said; I plummet into comprehension. "No," I say, certain. "You couldn't make me do that."

"I think you know that I could," he says, trapping me close to him with hands clasped above my elbows. "You're my strong-minded girl and I think you know exactly what I can do. Shall we make a promise, darling? Shall we promise to be honest with each other from now on? I shall make you into the most luminous queen."

"You can't make me hurt Mama," I say.

Father raises a hand and cracks me across the face. I'm blind and gasping and would fall if he weren't holding me up. "I can make anyone do anything," he says with perfect calm.