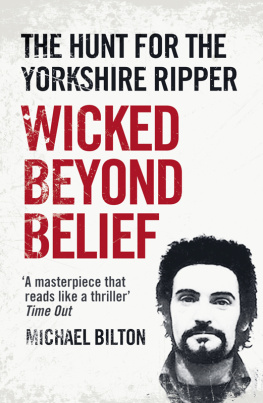

Sir Lawrence Byford: Report into the police handling of the Yorkshire Ripper case.

31 December 1978

It started snowing at Nottingham. It would not stop until the end of May.

The M1 was quiet that New Years Eve, a combination of the weather and the season. A cheap in-car cassette player belted out the hits: Tom Robinsons 2-4-6-8 Motorway, Rat Trap by The Boomtown Rats and inevitably, given my destination Kate Bushs extraordinary Wuthering Heights. Even at full, distorted volume it struggled against the straining engine of my overladen Mini.

I had been a journalist a reporter, as we were taught to term ourselves back then for less than a year, learning the trade on local weekly newspapers in the comfortable Surrey commuter belt. But now I was heading north, for a new job in what every newspaperman knew was the traditional heartland of good stories: Yorkshire.

And not just Yorkshire, and not just any good stories. I was bound for and, under the industrys strict apprentice scheme, bound to a paper in the epicentre of the area and the story that was then beginning to grip the nation. I was to join the local newspaper in Keighley the place where a vicious killer had apparently struck his first blows in what had been dubbed the Yorkshire Ripper murders.

The phrase had first been used ten months earlier. In early February 1978, the body of Helen Rytka, an eighteen-year-old prostitute, had been found in a timber yard in Huddersfield. She had suffered severe head injuries the result of being hit from behind with a hammer; she had also been stabbed thirteen times, causing savage wounds to her lungs, heart, liver and stomach.

Helen Rytka was, according to West Yorkshire Police, the likely eighth victim of the same serial killer. The severity and brutality of the injuries each had suffered and the fact that most were prostitutes recalled the crimes of Victorian Londons Jack the Ripper, and for more than two years the tabloid press had referred to Ripper-style killings. From Rytkas murder onwards this would be abandoned in favour of a shorter and pithier description: the man being sought was henceforth The Yorkshire Ripper.

The hunt for Britains newest serial killer exploded from being merely a regional story to dominating the front pages of national papers and television news headlines. The shocking and ritualistic nature of the Ripper murders was recounted extensively and feverishly; and while almost all the victims appeared then to be prostitutes, press coverage began to refer to a climate of fear affecting all women in the county respectable ladies as well as those who worked the streets.

For a young reporter with ambitions, Yorkshire was unquestionably the place to be.

A few miles south of Leeds scene of four presumed Ripper murders the M1 branches off to join the M62; foot pressed hard to the floor, I urged the overburdened little car up the exit slope and on towards Bradford (the location for two more).

Even under a softening blanket of snow, Bradford appeared grim: a shabby city grown out of its mill-town roots and falling on increasingly desperate times. A hundred years of pollution and grime clung to the millstone grit of row after row of terraced houses. Some places reek so deeply of poverty that their stench seeps in even through the closed windows of a speeding car. The Mini laboured on, struggling to shrug off the meanness of the city and to cope with the growing piles of soot-blackened slush and snow.

From Bradford the road wound up through the Aire Valley, past the once-proud villas of Manningham Lane now down-at-heel and an edge-marker for the citys red-light area towards Shipley and Bingley, and then on to the small town of Keighley, surrounded by the moors and memories of its literary luminaries, the Bront sisters. Wuthering Heights, indeed.

I would spend the next four years working for newspapers in West Yorkshire first weekly, then the regional daily, the Yorkshire Post. In those four years the callous blight of Thatcherism would take an unforgiving toll on an already struggling region: unemployment, poverty and desperation were its constant companions.

And fear, too. The Yorkshire Ripper would strike again and again, beating the life out of five more women, gouging and stabbing their stunned bodies in recession-hit back alleys across the county, and leaving yet others for dead. At least five of his murder victims were middle class and with no connection to the local vice trade.

Now terror was no longer a press exaggeration: families urged their women either to stay indoors at night or, if they must venture out, to do so in pairs. Darkness comes early in the northern winter: by mid-afternoon there was, in those Ripper years, a palpable tension in the streets.

That fear was heightened by the seeming powerlessness of West Yorkshire Polices Ripper Squad to catch their quarry. The largest manhunt in British criminal history was played out very publicly in newspapers, on television and radio, day in and day out. Poster campaigns, public appeals, telephone hotlines: nothing brought the detectives closer to the serial killer stalking Yorkshires streets.

And then it was over.

On 3 January 1981 exactly three years and three days since I had arrived in Yorkshire police issued the good news: a man they believed to be the Ripper was in custody.

Television news played footage of senior detectives smiling and relaxing for the first time. The time for fear was over: now it was time for anger. Crowds, baying for blood and revenge, crowded round police stations and flocked to the magistrates court where Peter William Sutcliffe a thirty-four-year-old lorry driver from Bradford was first arraigned.

Under English law, after someone is charged almost nothing about the alleged criminal can be published: the principle of innocent until proven guilty the emphasis being on proven is enshrined in statutes aimed at ensuring a jury is not prejudiced by bad publicity against the person facing trial before them.

If the public fed a television diet of American police procedurals where no such law applies was frustrated, journalists took the opportunity to spend the months before trial uncovering the life story of Peter Sutcliffe. Chequebooks were flourished; wads of cash flashed. Anyone with a story to tell and who could be bought was signed up on the spot. Those with the most precious commodity of all photographs could claim the highest price.

But if the nations press was hard at work on the who the man behind Britains longest run of serial killings who was at work on the why? Who would explain what drove this apparently happily married man to such savage butchery of women? We contented ourselves with the assurance that all would be revealed at his trial. Off the record, police officers hinted at psychiatric reports that would uncover the Yorkshire Rippers motivation. We settled down for a lengthy wait: no one expected the trial to take place until much later in the year.

We were wrong. And in almost every respect. Because Peter Sutcliffes trial began remarkably quickly less than four months from the date of his capture. And rather than a full and exhaustive examination, the prosecution had decided on much shorter and much more cursory proceedings.