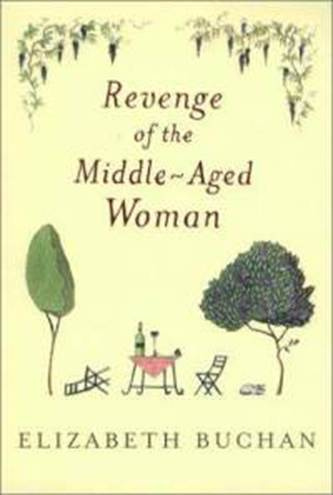

Elizabeth Buchan

Revenge of the Middle-Aged Woman

The first book in the Two Mrs Lloyd series, 2002

Living well is the best revenge

Old Spanish proverb

I took information on the Yanomami from The Times and on Rome from The National Geographic Traveller. I would like to thank Janet Bucks ladies for their information (they know who they are), Bernadette Forcey for the joke and Pamela Norris for her constant support. Also my brilliant editor, Louise Moore, and the team at Penguin, Clare Ledingham, my agent Mark Lucas and, as always, Hazel Orme, Keith Taylor and Stephen Ryan. This is not to forget my family and other friends.

Here, said Minty, my deputy, with one of her breathy laughs, the review has just come in. Its hilariously vindictive. She pushed towards me a book entitled A Thousand Olive Trees by Hal Thorne with the review tucked into it.

For some reason, I picked up the book. Normally I avoided anything to do with Hal but I did not think it mattered this once. I was settled, busy, different, and I had made my choice a long time ago.

When we first discussed my working on the books pages, Nathan argued that, if I ever achieved my ambition to become the books editor, I would end up hating books. Familiarity bred contempt. But I said that Mark Twain had got it better when he said that familiarity breeds not so much contempt but children, and wasnt Nathans comment a reflection on his own feelings about his own job? Nathan replied, Nonsense, have I ever been happier? and You wait and see. (The latter was said with one of his ironic, strong-man I know-better-than-you smiles, which I always enjoyed.) So far, he had been wrong.

For me, books remained full of promise, and contained a sense of possibility, any possibility. In rocky times, they were saviours and lifebelts, and when I was younger they provided chapter and verse when I had to make decisions. Over the years of working with them, it had become second nature to categorize them by touch. Thick, rough, cheaper paper denoted a paperback novel. Poetry hovered on the weightless and was decorated with wide white margins. Biographies were heavy with photographs and the secrets of their subjects life.

A Thousand Olive Trees was slim and compact, a typical travelogue whose cover photograph was of a hard, blue sky and a rocky, isolated shoreline beneath. It looked hot and dry, the kind of terrain where feet slithered over scree, and bruises sprouted between the toes.

Minty was watching my reaction. She had a trick of fixing her dark, slightly slanting eyes on whoever, and of appearing not to blink. The effect was of rapt, sympathetic attention, which fascinated people and also, I think, comforted them. That dark, intent gaze had certainly comforted me many times during the three years we had worked together in the office.

This man is a fraud, she cited from the review. And his book is worse

What do you suppose hes done to deserve the vitriol? I murmured.

Sold lots of copies, Minty shot back.

I handed her A Thousand Olive Trees. You deal. Ring up Dan Thomas, and see if hell do a quickie.

Not up to it, Rose? She spoke slowly and thoughtfully, but with an edge I did not quite recognize. Dont you think you should be by now?

I smiled at her. I liked to think that Minty had become a friend, and because she always spoke her mind I trusted her. No. Its not a test. I just dont wish to handle Hal Thornes books.

Fine. She picked her way round the boxes on the floor, which was packed with them, and sat down. Like you said, I know how to deal. I am not sure she approved. Neither did I, for it was not professional behaviour to ignore a book, certainly not one that would receive a lot of coverage.

My attention was diverted by the internal phone. It was Steven from Production. Rose, Im very sorry but we are going to have to cut a page from Books for the twenty-ninth.

Steven!

Sorry, Rose. Can you do it by this afternoon?

Twice running, Steve. Cant someone else be the sacrificial lamb? Cookery? Travel?

No.

Steven was harassed and impatient. In our business getting an issue out time dictated our decisions and our reactions. After a while, it became second nature, and we spoke to each other in a shorthand. There was never time for the normal give and take of argument. I glanced at Minty. She was typing away studiously, but she was, I knew, listening in. I said reluctantly, I could manage it by tomorrow morning.

No later. Steven rang off.

Bad luck. Minty typed away. How much?

A page. I sat back to consider the problem, and my eye fell on the photograph of Nathan and the children, which had a permanent place on my desk. It had been taken on a bucket-and-spade holiday in Cornwall when the children were ten and eight. They were on the beach, with their backs to a grey, ruffled sea. Nathan had one arm round Sam, who stood quietly in its shelter, while the other restrained a squirming, joyous Poppy. Our children were as different as chalk and cheese. I had just mentioned that a famous novelist had also taken a house in Trebethan Bay for six months to finish a novel. Good heavens. Nathan had made one of his faces. I had no idea he was such a slow reader. I had seized the camera and caught Poppy howling with laughter at this latest example of his terrible jokes. Nathan was laughing, too, with pleasure and satisfaction. See? he was saying to the camera. We are a happy family.

I leant over and touched Nathans face in the photograph. Clever, loving Nathan. He considered that the job of fatherhood was to keep his children so amused that they did not notice the unpleasant side of life until they were old enough to cope, but he also loved to make them laugh for the pleasure of it. Sometimes, at mealtimes, I had been driven to put my foot down: at best, Sam and Poppys appetites were as slight as their bodies and I worried about them. Mrs Worry, do you not know that people who eat less are healthier and live longer? demanded Nathan who, typically, had gone to some pains to find out this fact to soothe my fears.

Back to the problem. As always with the paper, there were political factors, none significant in isolation but, taken together, they could add up. I said to Minty, I think Id better go and fight. Otherwise Timon might get into the habit of paring down Books. Dont you think? The dont you think was cosmetic for I had made up my mind, but I had fallen into the habit of treating Minty (just a little) in the way I had treated the children. I thought it was important to involve them on all levels.

Timon was the editor of the weekend Digest in the Vistemax Group for which we worked and his word was law. Minty had her back to me and was searching for Dan Thomass telephone number in her contacts book. If you say so.

Do I hear cheers of support?

Minty still did not look round. Perhaps better to leave it, Rose. We might need our ammunition.

When it was a question of territorial battles, Minty was as defensive as I was. This made me suspicious. Do you know something that I dont, Minty? Not a silly question. People and events in the group changed all the time, which made it a rather dangerous place to work, and one had to become rather protean, undercover and dangerous to survive.

No. No, of course not.

But?

Mintys phone rang and she snatched it up. Books.

I waited a moment or two longer. Minty scribbled on a piece of paper, An ego here bigger than your bottom, and slid it towards me.

This implied that she would be on the phone for several minutes, so I left her to it and walked out into the open-plan space that was called the office. The management reminded its employees, frequently and cheerily, that it had been designed with humans in mind, but the humans repaid this thoughtfulness with ingratitude and dislike: if it was light and airy, it was also unprivate and, funnily enough, despite the hum of conversation and the underlying whine of the computers, it gave an impression of glaucous silence.

Next page