TO MY FAMILY

Contents

A Creation Myth of

Citizen Coke

I drank a lot of Coca-Cola. Growing up in Atlanta, the homeland of this famous soft drink, it was hard not to. After all, this was the product that helped make my town what it was. Few other southern cities could claim a business enterprise as big and powerful as the Coca-Cola Company. As former Atlanta mayor Andrew Young stated on the occasion of Cokes hundredth birthday in 1986, When we talk about Atlantas boom and our billions of dollars of new investments, you really have to give Coca-Cola credit. The company helped nurture what Young called a global, international perspective in this city when other cities appeared to be returning to the Dark Ages.

I realized over time that I was a Coke man for the same reason Milwaukee citizens were Brewers fans and Green Bay loyalists were cheeseheads: Coke was the industry that made my world possible. Coca-Cola, in my mind, was a builder. The Atlanta company was an ambassador to the world that we were proud to claim as our own because it was a force for good, a company recognized for its ability to solve problems wherever it went. It was a public citizen whose success ultimately improved the lives of those around it. This was Citizen Coke.

Coke had spent a long time, and a lot of money, promoting this image of selfless service. When Georgian pharmacist John Stith Pemberton created Coca-Cola in an Atlanta pharmacy in 1886, he advertised it as a brain tonic that Cures Morphine and Opium Habits and Desire for Intoxicants. Drink this, Pemberton ballyhooed, and all your mental and physical anxieties will vanish. This was magic in a bottle for a country that had just suffered long hard years of war and Reconstruction. Coke offered liquid serenity for a nation on edge.

From the very beginning, then, the Coca-Cola Company said it was in the business of public betterment, and its message was not entirely unfounded. Many of Cokes leaders over the years were magnanimous men who used corporate profits to build a better world. Pembertons successor, Asa Griggs Candler, who ran Coca-Cola from 1891 to 1916, gained widespread popularity in Atlanta for his charitable works. He was credited with executing monumental golden deeds, such as bailing out the Atlanta real estate market during the Panic of 1907 and offering million-dollar loan guaranties and direct aid to help Georgia cotton farmers during an agricultural depression in the 1910s. Candler was Atlantas first citizen, a man who used his wealth to improve the lives of others. Upon his death, the Atlanta Journal eulogized, Service, a beautiful and a noble term despite its worn usage, was the master motive of his well-nigh four score years.

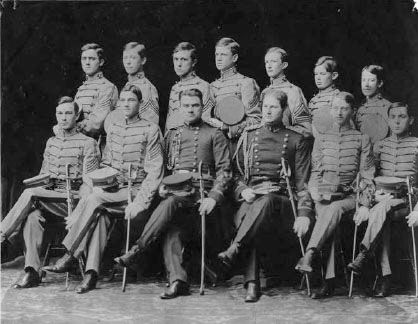

Robert Winship Woodruff, the Boss of Coca-Cola who remained the undisputed leader of the company from 1923 up to his death in 1985, garnered similar praise for being a man of the people. Woodruff gave millions of dollars, often anonymously, to charitable foundations around the world, and his largess helped to build formidable institutions in Atlanta, such as the Woodruff Arts Center and Emory University. In 1979, Robert Woodruff, along with his brother George, gave a $105 million gift to Emory, which was in fact the largest single donation to an educational institution at the time. I had a personal connection to Woodruffs beneficence, passing an imposing statue of the cigar-wielding Boss on my way to class at Woodward Academy, formerly Georgia Military Academy, a school Woodruff had attended as a child and generously supported as an alum. Other Atlanta residents have similar stories about Woodruffs humanitarian presence in their lives.

But charitable work, according to Woodruff, was just a small part of what made Coca-Cola good for the world. He believed that the business of selling Coke was philanthropy in and of itself. After all, by patronizing independent bottlers, local ingredient providers, and a host of private retailers, Coca-Cola helped create jobs even in some of the poorest parts of the world. Coke acted as a priming agent, as one company executive put it, stimulating a widening variety of trade activities wherever it went. The key was outsourcing. Coke did not integrate backward into ownership and management of suppliers, and because of this, Woodruff proclaimed, it helped bring economic prosperity to benighted parts of the world. Coke was not selling the world short, the Boss said, it was selling the world long. It was doing more by doing less.

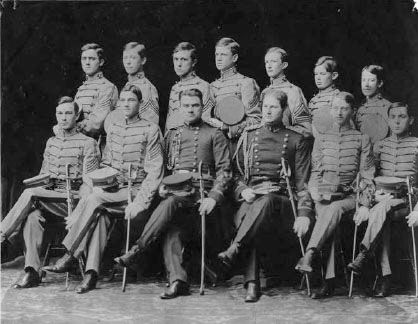

Georgia Military Academy (GMA) cadet officers in 1908. A grimacing Robert Woodruff, future president of Coca-Cola, is third from the left, back row. I attended this K12 institution, now Woodward Academy; it was renamed after Colonel Woodward, seated third from the left. I owe Robert Woodruff a debt of gratitude, as he generously supported my school with financial aid. In a way, he helped pay for my education.

What made Coke so appealing economically was that it seemed to ask very little for the rewards it generated. Time magazine captured this image of Coke in 1950: Coca-Cola is not what the non-American thinks of as a typical U.S. business, like steel or automobiles. It is not a product of the vast natural resources of the land, but of the American genius for business organization. It rests on such intangibles as market analysis, sales training, advertising and financial decentralization. According to Time , Coke placed few demands on the provider communities that supported it. The company could grow without consequence for centuries to come, and the world would be a better place because of it.

This illusion of self-sustainment helped Coca-Cola justify its expansion into communities around the world. The company was an invited guest in many international polities because it was seen as a low-cost enterprise that would stimulate local economies. Few stopped to consider what the company asked of them, thinking only of what they could ask of the company.

But as Coke began to expand its commercial empire in the latter half of the twentieth century, it became clear that the promise of big profits for little cost was more fiction than fact. Coca-Cola and other similar mass-marketing companies were consumers as much as they were producers, and they required natural resources in order to survive. Over time, Coke placed heavy demands on ecologies around the world. It was an organic machine whose perpetual growth was contingent upon the extraction of abundant supplies of natural, fiscal, and social capital in the places where it operated.

Like many other people across the world, I benefited from what Cokes profits provided but had only a vague notion of how those profits were generated. This book was an attempt to understand the demands Coke placed on provider communities that served its needs for the last 128 years, an attempt to examine Citizen Coke as a consumer rather than as a producer. It was as much a historical quest as a journey to understand the economic and ecological reality behind all that Coke I drank growing up.

C oca-Cola was the worlds most valuable brand in 2012. That year, the company was all over the map, operating in over two hundred countries and selling more than 1.8 billion beverage servings per day (one serving for every four people on earth). It was the twenty-second-most-profitable company in the United States, with revenues topping $48 billion and net income over $9 billion, making it one of the greatest profit-generating businesses in world history. By the twenty-first century, Coke had conquered the globe, its market reach unmatched.

Next page