RETHINKING THE KEYNESIAN REVOLUTION

RETHINKING THE KEYNESIAN REVOLUTION

Keynes, Hayek, and the Wicksell Connection

By Tyler Beck Goodspeed

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2012 by Oxford University Press

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goodspeed, Tyler Beck.

Rethinking the Keynesian revolution : Keynes, Hayek, and the

Wicksell connection / by Tyler Beck Goodspeed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780199846658 (cloth :alk. paper) 1. Keynesian economics.

2. Keynes, John Maynard, 18831946. 3. Hayek,

Friedrich A. von (Friedrich August), 18991992.

4. Wicksell, Knut, 18511926.

I. Title.

HB99.7.G656 2012

330.156dc23

2011051633

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For Professor Medoff

CONTENTS

RETHINKING THE KEYNESIAN REVOLUTION

INTRODUCTION: RETHINKING THE KEYNESIAN REVOLUTION

Reflecting on a Keynesian revolution of which he himself was a principal architect, Nobel laureate Sir John Hicks remarked that when the definitive history of economic analysis during the 1930s comes to be written, a leading character in the drama (it was quite a drama) will be Professor Hayek. Though Friedrich von Hayeks economic writings are almost unknown to the modern student, Hicks observed, there was a time when the new theories of Hayek were the principal rival of the new theories of Keynes. Which was right, Keynes or Hayek?

After a hiatus of a few decades, Hickss question is once again in vogue among macroeconomists. The academic consensus that coalesced, in the decade preceding 2008, around a standard dynamic stochastic general equilibrium class of economic model has since frayed. Indeed, IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchards August 2008 declaration that the state of macro is good, and that a largely shared vision both of fluctuations and of methodology has emergeda sentiment echoed as late as January 2009 in the macroeconomic issue of the American Economic Journal, by Michael Woodfords rather ironically (in retrospect) titled article Convergence in Macroeconomics: Elements of the New Synthesisseems subsequently to have given way to a sense of crisis, and awkward discord, in the economics profession not seen since Milton Friedman declared the death of the Phillips curve in 1968, or possibly even since Keynes and Hayek sparred in the pages of the Economic Journal in 1932. Both men have thus been duly hauled out of, at times, ignominious retirement as standard-bearers of competing visions of the operation of a market economy. A comedic Keynes vs. Hayek YouTube rap, along with an encore sequel, even went viral in 20102011.

From the perspective of the history of economics, however, Keynes or Hayek is in many respects a flawed question; the consensus that ultimately emerged, and, discord notwithstanding, largely persists still in modern macroeconomics is neither Keynesian nor Hayekian but rather unmistakably Walrasian. Moreover, contrary to the popularized rivalry, Keynes and Hayek not only shared far more theoretical ground than is typically realized but also held a deeper theoretical affinity with one another than with modern macro.

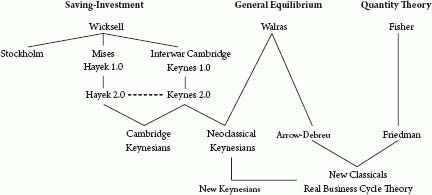

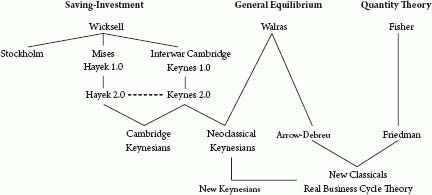

The source of that affinity, I argue, is the Wicksell connection. It effectively ended with Keynes and Hayek. As the following family tree of twentieth-century macroeconomics illustrates, since the merger of the quantity theory tradition of Irving Fisher with Walrasian general equilibrium, by Robert Lucas and the New Classicals, all mainstream schools of macroeconomic thought, including both the real business cycle theorists and the so-called New Keynesians, have adhered to the Walrasian approach. Of the postwar Keynesian schools, only flotsam and jetsam remain. We are all Walrasians now.

The notion of a Wicksell connection was first conceived by economist Axel Leijonhufvud in the mid-1970s, a time of acute crisis for the New Keynesians Neoclassical Keynesian predecessors, to highlight Keyness kinship with a theoretical approach to monetary economics, separate from the quantity theory line of Irving Fisher and Milton Friedman, established by late nineteenth-century Swedish economist Knut Wicksell. Unlike the quantity theory and Walrasian traditions, which assume the rate of interest either to always and perfectly coordinate saving and investment or else to reduce it, in the latter case, to merely an infinite set of simultaneously determined intertemporal price ratios, the Wicksellian approach hoists the problem of intertemporal coordination front and center, with the interest rate as the decisive variable.

Figure I.1

It is the argument of this book that not only did Keynes and Hayek both adhere to the Wicksellian approach, but also that the Wicksell connection was, as a result, responsible for a fundamental convergence of their respective theories of money, capital, and the business cycle during the course of the 1930s. In short, Keynes and Hayek were not quite the theoretical antagonists they were, and have since been, made out to be.

Our Wicksell connection linking, or bridging the gap between, Keynes and Hayek consists of three primary themes, all of them tightly interrelated. The first is that money matters. From the perspective of economic theory, this is a by no means trivial point. Joseph Schumpeter described it as the difference between real and monetary analysis. The former assumes that monetary issues may be analyzed separately from the determination of equilibrium in a system of perfect barter, introduced at a later stage without disrupting the results of preceding stages of analysis in strictly real terms, while the latter maintains that money must be admitted into our analysis from, so to speak, the ground floor.

The core of the Wicksell connection is, in contrast, the integration of real with monetary analysis. As Hayek noted in his Prices and Production (1931), The task of monetary theory is nothing less than to cover a second time the whole field which is treated by pure theory under the assumption of barter, and to investigate what changes in the conclusions of pure theory are made necessary by the introduction of indirect exchange. The neo-Walrasian theorist hence acquits himself of the very task to which both Keynes and Hayek assigned economic theory.

Next page