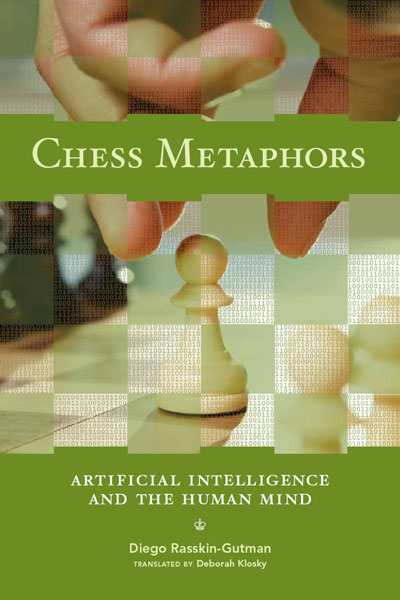

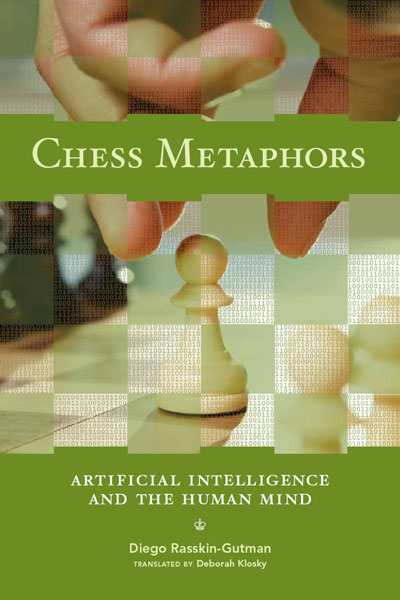

Chess Metaphors

Chess Metaphors

Artificial Intelligence and the Human Mind

Diego Rasskin-Gutman

Translated by Deborah Klosky

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about special quantity discounts, please email .

This book was set in Stone by Graphic Composition, Inc.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Metaforas de Ajedrez. English

Chess metaphors: artificial intelligence and the human mind / Diego Rasskin-Gutman; translated by Deborah Klosky.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-18267-6 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1.ChessPsychological aspects. I. Title.

GV1448.R37 2009

794.1019dc22

2008044226

Originally published as Metforas de ajedrez: la mente humana y la inteligencia artificial, Editorial La Casa del Ajedrez, Madrid, 2005

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Debbie, Gabriel, and Alexander

Contents

Foreword by Jorge Wagensberg

Preface

1 The Human Brain: Metaphor Maker

2 The Human Mind: Metaphor of the World

3 Artificial Intelligence: Silicon Metaphors

4 The Complete Metaphor: Chess and Problem Solving

5 Chess Metaphors: Searches and Heuristics

Epilogue

Appendixes

A The Rudiments of Chess

B Chess Programs and Other Tools

C Internet Sites for Playing Chess

Bibliography

Index

Foreword

Ive been ensnared by chess during two periods of my life. The first time was when I entered the physics department as a university student. The second was last summer while I was pondering a metaphor from Richard Feynman comparing the observer of coffee-house chess games to a scientific researcher. In both cases, something similar happened: chess took over a large part of my conscious and unconscious thoughts.

In my youth, the boredom of classes (when the professor insisted on presenting things that could be read in books) pushed me into a nearby bar where speed games were played. At night, I would go to a club to help prepare games for the local tournament that was played on Sundays. After the games, I often dreamed about them: if I won, I dreamed that I lost; if I lost, I dreamed that I won. The brain has evolved throughout millions of years to anticipate uncertainty, and its joy lies between two limitsthe offense when the uncertainty is too low (and the challenge is trivial) and the frustration when the uncertainty is too high (and the challenge is inaccessible). In that era, my mind was nourished more by coffee-house chess games than the canned science of university courses. But is it possible to speak of uncertainty in the case of chess? There are ten raised to the power of 120 different games. So, yes, it is possible to speak of uncertainty. Each player contains a ration of uncertainty for his adversary. The number of subatomic particles in the universe is on the order of ten raised to the power of eighty, and the number of different free sonnets that can be written in Spanish (fourteen verses chosen from among 85,000 words) is ten raised to the power of 415. In chess, the brain holds an illusion of creating, the same as when a poet writes a sonnet or when a scientist proposes a law of nature, taking the improbable chance that nature will accept it. In that period of my life, to create was to create chess games.

This last idea has to do with Feynmans metaphor, a brilliant idea that just a few months ago pushed me for the second time into the arms of chess. An onlooker of coffee-house games, who does not know the rules, can discover them if he observes a sufficient number of encounters. The metaphor, like all good metaphors, is rich in possibilities for thinking about the scientific method and philosophy of sciencericher, even, than Feynman himself intended.

On both occasions, it was not easy for me to regain enough distance from chess to be able to concentrate on other parts of my daily tasks. But my friend Diego Rasskin-Gutman suddenly sent me the galley proofs of his last book. I opened the package. Danger. I recognized the sensation. I felt again that free-fall into the depths of chess. How is it possible that this many things about a wonderful game escaped me? How is it possible not to know about its historical origin as an oraclethat is, as an instrument for treating uncertainty? I had intuited many relations between chess and art, between chess and aesthetics (which is not the same), between chess and science, and between chess and intelligibility (which is also not the same), but it is one thing to intuit and another to know. I was lost. I looked for somebody with whom to play. I looked for memorable games from the past from my old mythsthe brilliant Tahl, the astonishing Fischer, the legendary Capablanca, the amazing Najdorf, the solid Petrosian. I looked for someone with whom to talk about chess. But I was also struck by new preoccupations. Chess serves up metaphors, but it also serves up paradoxes, forms, methods, feelings, ideas, techniques, speculations, histories, indications, stimuli, intuitions, knowledge. This book by Diego Rasskin-Gutman is filled with all that. It gives the impression that the ideas in this work have been turning over and over in the mind of a scientist who is interested in everything that has to do with the complexities of the world while he thinks about science, plays chess, or contemplates a work of art. I will be lost in its ideas for a long time. And now that makes threeone captivity during my university days, another at the hands of Richard Feynman, and now yet another at the hands of Diego Rasskin-Gutman.

Jorge Wagensberg

Barcelona, May 2005

Preface

Gabriel looks at Alex. Alex smiles, provoking in his older brother a spontaneous laugh. Four-year-old Gabriel says, Papi, Alex is little, and he doesnt understand what you say. After that, we read a book. He looks at me with admiration: Papi, how can you do that? Do what?, I say with surprise. That, he says. How can you know the end of the story? I look tenderly at him, as you do when contemplating the candid curiosity of a child, and gaze at Alex too, who is still smiling, caught up in the world of a just-about-one-year-old. The three of us laugh, and we wrestle on the sofa.

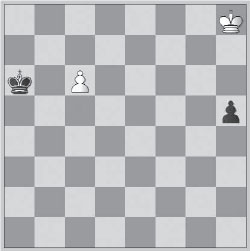

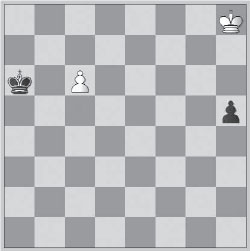

The same type of fascination that floods the mind of a child when he observes an adult performing trivial and everyday tasks with such skillfulness is at the origin of this book. I am talking about the sense of awe that I feel when following the games of the great chess players or the overwhelming emotion that I felt when suddenly I understood Richard Retis composition (shown in the diagram above). I remember how on that occasion, I hardly had time to show my own father how white can avoid losing thanks to the geometry of the board (moving the king to the g7 square draws the game). But at many other times, I have been unable to comprehend all the subtleties that come in many of the moves, ideas, or strategic plans of the great players. In sum, I felt like my four-year-old sonin awe of a complexity (or simplicity) that escaped me.

Next page