Better Thinking, Better Chess

Joel Benjamin

Better Thinking, Better Chess

How a Grandmaster Finds his Moves

New In Chess 2018

2018 New In Chess

Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands

www.newinchess.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher.

Cover design: Ron van Roon

Supervision: Peter Boel

Editing and typesetting: Ren Olthof

Proofreading: Maaike Keetman

Production: Joop de Groot

Have you found any errors in this book?

Please send your remarks to and implement them in a possible next edition.

ISBN: 978-90-5691-807-1

Explanation of symbols

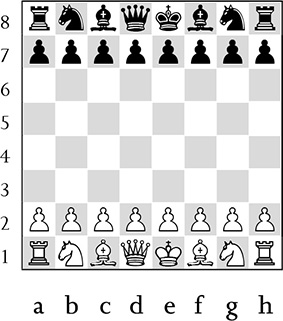

The chessboard with its coordinates:

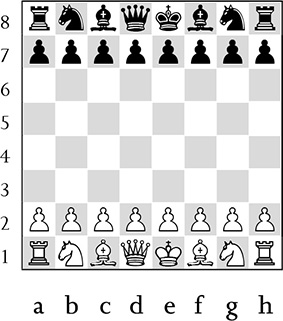

| White to move |

| Black to move |

King |

Queen |

Rook |

Bishop |

Knight |

| White stands slightly better |

| Black stands slightly better |

| White stands better |

| Black stands better |

+ | White has a decisive advantage |

+ | Black has a decisive advantage |

= | balanced position |

! | good move |

!! | excellent move |

? | bad move |

?? | blunder |

!? | interesting move |

?! | dubious move |

Introduction

As a player I was aware of my own thought processes, but my second career as a teacher and coach gave me insights into the way other people approach their chess games. I realized that pointing out the moves players missed was just half the job. I needed to explain why they didnt arrive at the right move, and what they could do to improve their chances for the next time.

Most chess books focus on providing chess knowledge and positions for training and study. Developing these skills can help bring players up to a higher level. This is the work between games. But the work during games is no less important. I find that so many players could get more out of their abilities by doing a better job at the chessboard. This work manifests in many ways, such as looking for and thinking about the right things, not taking shortcuts in the search for moves, and not getting held back by preconceived notions and psychological limitations.

Stronger players have an advantage not only in what they know, but also in how they apply it. Working with students on virtually all levels, in classes, camps, and private lessons, I have seen players trip up not so much by lack of knowledge or skill but by flawed thinking. There will always be cases where a solution is beyond the abilities of a player, or, at the very least, a concentrated, good-faith attempt at finding the right path doesnt yield the correct continuation. A 2000 player cannot be judged by the same standard as a grandmaster. But that player should still make every move and every decision to the best of their abilities. How often are mistakes made by silly oversights or lazy calculation? How many strong moves are overlooked because we simply dont consider alternatives? Fundamental failings in the thought process cause so much damage, yet I believe we can all train to get better in those areas.

I have included several games played by students. Though these games generally represent failures, I must point out that my students are generally highly rated, especially for their ages (the range is about 2000-2500). If they were not so successful in most of their games, I could not in good conscience use their games for these purposes. If they make these mistakes, surely less talented players are as well. Because I have discussed the games with my students, I have a good sense of what they were thinking, and how their thought processes might have led to mistakes.

I have found that failure to calculate long variations correctly accounts for a small percentage of their errors. Usually problems occur from something more fundamental, often early in deliberations. Talent and maturation tend to overcome deficiencies in thinking, but I think that older players who may feel stuck at a certain level can still improve their performance with more structured and efficient thinking.

I have chosen my own games for the bulk of source material, not because they are more instructive than those of other players, but because the thought process is familiar to me. I can explain why my mind went in some directions and not others. Most of these games represent successful chess thinking, though a few failures stand out as well. I have tried to focus on the approach that brought me to the solutions of these practical problems. That is not to say that readers would necessarily find the same moves by reproducing my train of thought, but by using this type of (usually) clear thinking they can better solve problems in their own games.

I have tested many of these positions in lectures, classes, and lessons. The experience has helped me understand how other players approach practical problem solving, and how they might benefit from adjusting their thought process in line with a grandmasters method.

Contemporary chess is inextricably linked with chess engines. How to properly understand and use chess engines is a topic that needs to be addressed in the chess literature, and I frequently discuss computer evaluations in this book. Every chess author uses engines to check and to some degree generate variations and assessments. Computers spot amazing possibilities that enrich our understanding and appreciation of chess. I found in writing the autobiographical American Grandmaster that many of my old games felt a lot different from this new perspective. During the process of writing this book, a decade later, engine analysis continues to shine new light on these older games. We should never ignore this output, but we need to remember we dont get machine assistance during our games (unless we are cheating; dont do that!). Much of what engines tell us is not accessible and meaningful when we are actually playing a game.

Komodo was my partner in this project; while its advice was welcome and enlightening, I did not treat its data as gospel. I have come to view chess positions as having alternative realities; an objective reality based on computer analysis, and a practical reality based on what we can plausibly calculate or anticipate during a chess game. In this book I recommend a path towards practical reality.

Consider these situations: you have a large and potentially winning advantage that can be maintained by simple means, yet you embark on a wild sacrifice. The decision backfires and the game is lost. Afterwards, the computer confirms the sacrifice was sound, and winning by force. The decision was still foolish, in my opinion, because you put yourself under pressure to come up with a move you didnt foresee (and perhaps would not have been able to find), or perhaps you didnt anticipate your opponents defense at all.

Next page