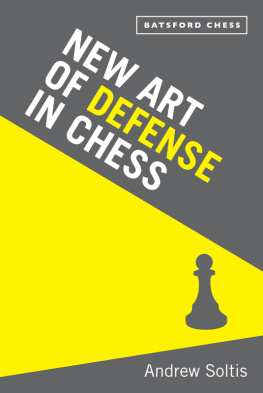

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

The paperback of this book can be ordered direct from the publisher at the website

www.anovabooks.com

Introduction

S o why do we need a long term plan? Didnt Capablanca show that you can become World Champion by taking it easy and playing natural moves?

If your philosophy is put pieces on good squares and dont worry about an overall plan or tactics! you are in effect playing Russian Roulette. Sooner or later someone will be mopping bits of brain off the chess board, which is bad news even for someone who doesnt like to think too much.

Even if you have a good intuition when it comes to picking moves with the capacity to be good, in each position as a game progresses you will probably encounter five or more moves that look right. Sooner or later you will pick one that looks right but is actually a disguised tactical/strategical blunder.

Capablanca is dead; and the rest of us need to play with our brains as well as our hands.

Having said that, we can make things a lot easier for ourselves. Everyone learns variations in the openings, but rarely do they pause to reflect on the connection between the moves played and the underlying strategic demands of the position. Instead its moves and moves and more moves! But surely a grasp of the chess principles at work would not only make you a better player but also make the learning of theory easier and more enjoyable.

In Chapter Six we shall see that even the great Steinitz, the first World Champion, is clueless when confronted with an unfamiliar pawn formation. So you might think that there isnt much hope for the rest of us.

Fortunately (or unfortunately if you wanted to be a pioneer yourself) more than a century has passed since Steinitz played his chess. Thats an awful lot of tournament and match chess. The never ending arms race of ideas, (or less grandiosely trial and error) has bequeathed to modern players the knowledge of how to play various pawn structures.

In writing this book Ive tried to take a step back from opening theory: to forget for a moment the endless reams of analysis of the Sicilian and Kings Indian, and simply ask myself: what does the pawn structure require and how does the placement of the pieces, including the king, warp this requirement?

Move by move coverage has been given to the most important phases of each game, during which the long term plan unfolds. Sometimes the game is of such value that every step along the way after the opening has been carefully considered.

I hope you enjoy the games. Let me wish you a lot of success and joy in learning the art of strategy from these great minds.

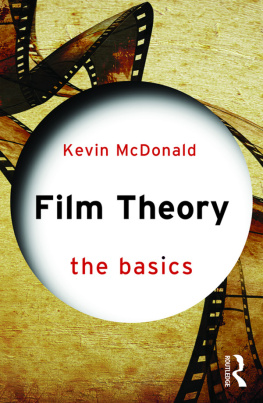

Neil McDonald

Gravesend

August 2007

Chapter One:

The smiting style

Chess is 99% tactics.

Richard Teichmann

Examine moves that smite! A good eye for smites is far more important than a knowledge of strategical principles.

Cecil Purdy

Many years ago I recall that Karpov and Korchnoi were asked to comment on the above quotation from Teichmann. Korchnoi more or less agreed, while Karpov replied rubbish! (or maybe it was nonsense! but you get the meaning). You can draw your own conclusions from this.

But no one can deny that it is essential for any serious player to train their tactical eye. The Viennese Grandmaster Richard Reti wrote two famous books on chess strategy in the 1920s, called New Ideas in Chess and Masters of the Chessboard. In these brilliant tomes Reti kept variations to a minimum and explained things in words wherever possible. And yet he was anxious to point out that:

Tactics are the foundation of positional play!

And rightly so. A player needs to proceed from the simple to the complex: if you havent mastered basic tactical devices such as forks and skewers there is no hope of ever playing a good strategic game.

By smites Purdy means moves that attempt to land a combinative blow on the opponent. He is giving excellent advice in recommending a bold, forceful method of play to those keen to deepen their awareness of possibilities on the chess board: nothing can develop the imagination as much as experimenting with ideas.

For this reason the Kings Gambit with its scope for sharp attacks and sacrifices should be the opening of choice for a player seeking to learn the ropes of tactical chess.

Every chess master was once a beginner

Chernev

To begin at the beginning, lets look at some youthful smiting:

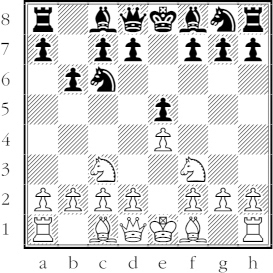

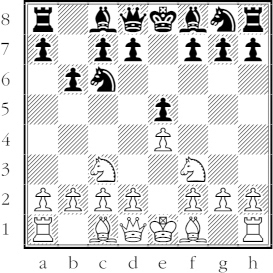

Game 1

Two schoolboys in battle

e4e5

01;f3

01;f3 01;c6

01;c6

01;c3

01;c3

So far so good: sensible developing play by both players. But at this point theory seems to come to an end for Black.

3 b6?

Black plans an attack on the white e4 pawn, but it is a luxury he cant really afford. He should develop with 3  f6 or 3

f6 or 3  c5.

c5.

d4

Not the best: 4  b5! would threaten 5

b5! would threaten 5  xc6 dxc6 6

xc6 dxc6 6  xe5. Black cannot reply 4 d6, his normal move in this type of position to bolster e5, as that would leave the knight on c6 hanging. Hence we see that 3 b6 has not only squandered a tempo but also undermined the ability of the black pieces to hold onto the e5 pawn.

xe5. Black cannot reply 4 d6, his normal move in this type of position to bolster e5, as that would leave the knight on c6 hanging. Hence we see that 3 b6 has not only squandered a tempo but also undermined the ability of the black pieces to hold onto the e5 pawn.

Whites 4 d4 move is typical of this variation it is for example a standard response to 3  f6. It also makes sense to break open the centre seeing that Black has wasted a move with 3 b6. But it also shows a certain rigidity of thinking.

f6. It also makes sense to break open the centre seeing that Black has wasted a move with 3 b6. But it also shows a certain rigidity of thinking.

In forcing the exchange of pawns on d4, White is rather generously ridding Black of the pawn on e5 which it would have been hard for him to defend after the superior 4

01;f3

01;f3 c5.

c5.