The New Art of Defense in Chess

Andrew Soltis

Contents

Introduction

This book came about because of something I didnt expect to find in my bookcase. It was one of my earliest efforts, The Art of Defense in Chess. I had fond memories of it so I opened it up and leafed through the pages.

It was not what I remembered. The book was drastically out of date. This has to be completely rewritten, I thought.

Out of date? A book about defense?

Yes, because much of what I wrote about the virtues of solid but passive restraint, for instance makes little sense nowadays. It would fail against todays attacking players. They think differently from those of 30-plus years ago.

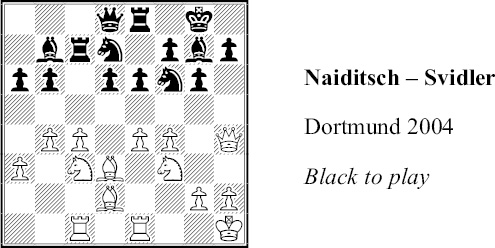

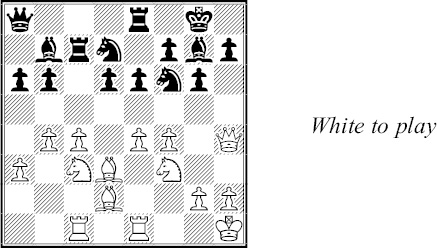

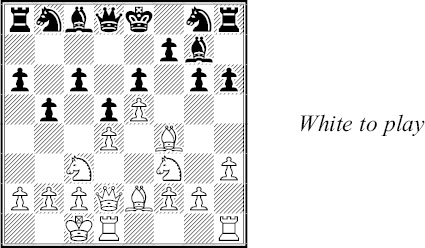

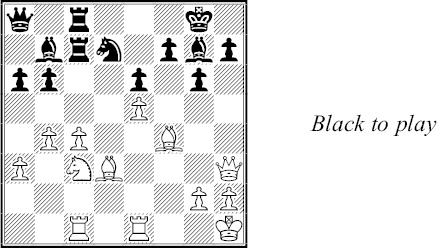

In 1974, the year I wrote The Art of Defense in Chess, this would have been considered a favorable position for White, a plus-over-equals advantage, at least:

White has a substantial advantage in space. Black has failed to execute any of the freeing moves, such as ... b5 or ... d5, that he needs to survive in this Maroczy Bind pawn structure. White will eventually find a winning plan, such as with e3, g5, h3 and a breakthrough around h7.

And Whites attack would likely have succeeded if Black played in the manner that served so well for much of the 20th century, with cautious moves such as ... f8 to protect h7 and to avert 2 e5? because of 2 ... xf3 3 gxf3 dxe5 and ... xd3.

But today most masters would prefer to play Black, particularly after 1 ...a8!.

Why? Because we realize now that Whites space advantage, in this and similar positions, is vastly overrated. And we see Black has a powerful plan of 2 ... fc8 and 3 ... xc4! 4 xc4 xc4. That trumps anything White is doing on the kingside.

But you cant sacrifice in even positions, can you? Thats what 1974 would say if it could speak.

Yes, you can, we say today. Black would have one pawn for the Exchange and powerful pressure on the e4-pawn as compensation after 4 ... xc4.

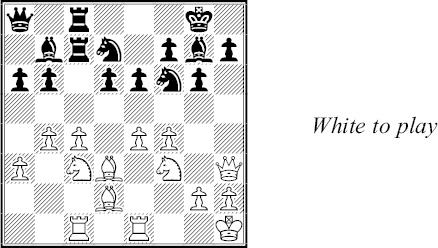

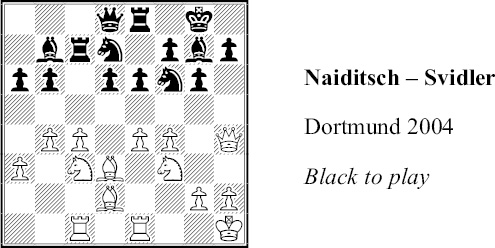

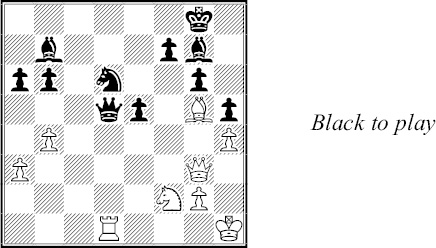

In fact, White retreated h3 (!) to anticipate threats along the a8-g2 diagonal. He was no longer acting as an attacker. He was beginning to think like a defender. Black continued to think like a counter-aggressor, with 2 ...ec8.

In the next diagram, 3 g5 would try to take Blacks attention away from ... xc4. It would offer good practical chances after 3 ... h6 4 xf7! xf7 5 e5, for example.

What should Black do after 3 g5? Heres where the solid 3 ... f8! makes sense and would put the pressure back on White.

In the game, White chose 3 e5 instead of 3 g5. But 3 ... dxe5 4 fxe5 h5 would threaten ... xf3/... xe5. If White defends with 5 e2 it would be time for 5 ... xc4! 6 xc4 xc4. Black would have the upper hand in view of 7 ... xf3 and 7 ... f4.

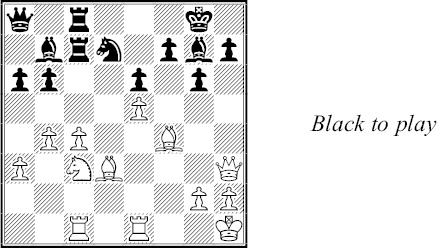

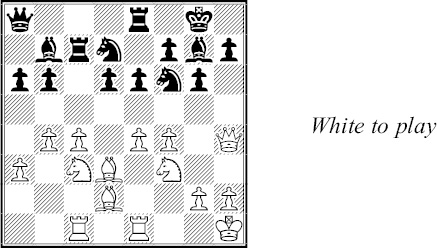

Instead, play went 3 e5 dxe5 4xe5 and then 4 ...xe5 5 fxe5d7. There was only one way to protect the e5-pawn, f4.

Black finally pulled the trigger, 6 ...xc4! 7xc4xc4. If he wins the e5-pawn he will have more than enough comp for the Exchange and excellent winning chances.

Whites g3 was natural (but 8 e2 was better). And 8 ... h5! was a surprise. Instead of trying to cash in, 8 ... xg2+ 9 xg2 xg2+ 10 xg2 xf4, Black was content to build pressure with the threat of 9 ... h4! and, if allowed, 10 ... h3!.

Unfortunately for White, this illustrates a fact of defensive life: It is easier to safeguard a compact position than one with pieces and pawns spread over a large area, as Whites forces are. His e2? was a final error, punished by 9 ...xe5! (based on 10 xe5 g4).

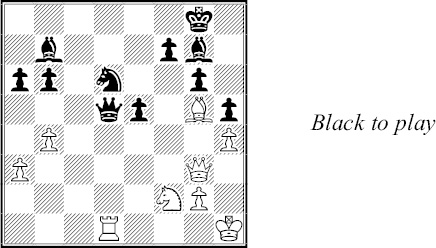

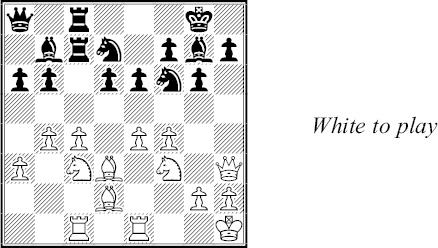

The rest of the game was interesting chiefly because of the finish: xc4xc4 11 h4d8 12g5d7 13f4 e5! 14d3d5 15f2d6 16d1.

And 16 ...e4! prompted resignation.

This is the way chess is played today. Anyone who plays over attacking games of the 21st century will be struck by how they differ from 20th century games. You can argue that the biggest change since the 1970s is that our play has been refined by computer analysis. But it was transformed earlier by the revolution in middlegame thinking led by Mikhail Tal.

Strangely enough, it was the greatest attacker of modern times who inspired new methods of defense. Why? Because Tal changed the way sacrifices and the initiative were evaluated: He won many games because his opponents had never before been confronted by a highly speculative sacrifice. Or by an attack launched by Black right out of the opening. Or by complications that defy exact analysis.

Tal presented a way to attack that confounded traditional defensive thinking. But according to the iron law of strategy, the defense always catches up with the offense. This book is about how a different approach evolved to meet the demands of changing times. This is New Defense.

Chapter One:

What is Defense?

When the first edition of this book appeared, readers told me how struck they were by the very first example. It wasnt a famous game. Far from it. But there was something about the way it unfolded:

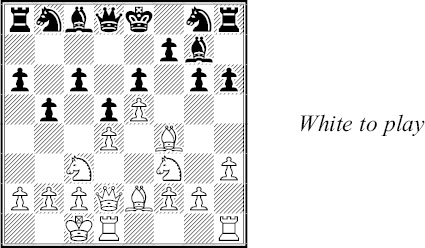

Klyavin Zhdanov, Latvian Championship 1961

1 e4 c6 2c3 d5 3f3 g6 4 d4g7 5 h3 a6 6f4f6? 7 e5g8 8d2 b5 9e2 h6 10 0-0-0 e6

It didnt take readers long to conclude that White has a very strong position. He has brought out nearly all of his pieces while Blacks only developed piece, his KB, bites on granite at e5. Blacks queenside is riddled with holes on dark squares and he has just locked in his other bishop. You might expect a quick mating attack. You would be right:

11 g4d7 12g3f8! 13df1b6 14d1 a5 15e1 b4 16d3c4 17e1b6 18 b3xd4! 19 bxc4a1+ 20d2 dxc4 21f4xa2 22e3!?b7 23d2 g5 24h5 c3 25d3d8 26e4c5+ 27