I have so many wonderful people to thank for helping me write this book. Most important, is my husband, Dan, who has been supportive on every front. He tended to my candy business so I could stay home writing, and he cooked and cleaned, brought coffee to my desk, and was always ready with love and laughs. You were rightI am still a writer. And you helped me have the chance.

Then there's my agent, Grace Freedson, who convinced me that after writing nine books, a tenth was in order. It's been years for us, and I owe you many thanks.

I'm also so appreciative of my neighbor and friend Karen McMullen, who checked in, gave help whenever I needed it, and came up with ideas and glasses of wineas always, a mensch! And Michael Spencer, who has taught me much about plants, history, and legacy, and further helped with insights and books.

Television director Tucia Lyman was amazingly supportive of this book, even while coping with my acting. She and her crew were wonderful. The show must go on and it did. Big thanks to the folks at Four Seasons Books for finding impossible-to-find books for my research on a truly impossible timetable. And to the wonderful David Kleinthanks for your story, your ongoing interest, and above all, for inventing the Jelly Belly!

And speaking of stories, big thanks to those who shared their stories with me for this book: David Rawls, Dabney Chapman, Wilma Green, Timothy Keady, Paul Palmer, John Gunther, Shelli Dronsfield, Bob Burkinshaw, John Gibbs, sisters Dorothy Van Steinburg and Chris Houck, Bob Tuck, Ethel Weiss, Howard Nachamie, and Edith Elizabeth Lowe Higdon and her granddaughter, Michelle Robinson, who arranged the interview. Many thanks also to Lois Nachamie for her wonderful encouragement, and to Leni Sorenson, whose insights were so helpful. Also, thanks to my brother, Mark Benjamin; my father, Richard; and my mother, who agreed to an interview.

Finally, thanks to Steven L. Mitchell, my editor, and the folks at Prometheus for giving me the opportunity to write this book. Last, and hardly least, Jan Hafer, Donna McAleese, and the others in my sign language group; we did it! We came up with a title, finger spelling and all.

It's been three months since I finished this book; since then, much has happened. Dabney Chapman, who I interviewed about his mother's toffee and his father's family's rock candy, died. Bob Tuck's wife of fifty-four years also passed away. My husband, Dan, left to spend a year in a war-torn part of Afghanistan, something neither of us quite expected. As for my father: he's now in an assisted living facility. My mother rarely visits him.

Shortly after I completed the text, my editor, Steven Mitchell, suggested I write some kind of conclusion about where candy is today. He was rightI did need a conclusion. After considering the message for several weeks, here's what I have to say: Today's candy is cheaper than it was before, largely mass-produced, and void of cultural meaning. The flavors are largely concocted in a lab, as are the textures and colors. Marketers play a bigger part in candy making than ever before, and visionary candymakerslike John Curtis and Mary Spencerare hard to find.

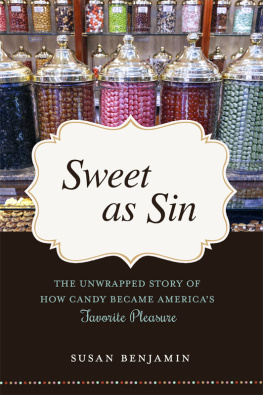

But it's important to remember that plenty of candies are still made in small stores, and all sweets, from the mega-sized gummies to the super-sour hard candies, share a remarkable, uniquely American history. Besides, so many of those who have passed, those who survive, and those who go on to do brave things, have held candy at some central place, a truly dear and love-filled place, in their lives. Love it, hate it, or consider it deliciously sweet as sin, candy occupies that place in most of us today.

My husband, Dan, and I were in New York recently attending the Fancy Food Show. In case you've never been, it's an event of events if you happen to like food. There are thousands of vendors from all over the world with samples they not only give away but insist you enjoy. Never mind I was looking for candymakers, of which there was an abundant supply, but I also sampled from a multitudinous selection of Spanish olives and a much-too-good alcohol blend presented by a contingent from Mexico. After a two-hour stomach-settling respite, we met out friends Lois and Howie for dinner at a Korean restaurant near 35th Street. While we were enjoying buns, barbeque, and kimchee, I happened to mention that my mother hates candy. And that she's always hated candy. Evennoespecially when I was a kid.

Lois, who happens to be a psychotherapist, gave me one of those aha! looks. She knows my mother and I have problems and that I research and sell candy for a living. Ask me a question, and I'll steer it around to candyit's my personal brand of narcissism. But despite what Lois may think, the reason I love candy has nothing to do with my candy-hating mother.

As for Lois, she enjoys your odd caramel or chocolate but was taking a time-out from sweets as part of a cleansing diet. I understood and took no offense, although personally I'd never do it. My husband, Dan, loves candyespecially bourbon ballsand he'd eat them at any given moment. In fact, he hides them from himself at home so he won't eat too many, though with uncanny skill, he still manages to find them.

Howie's different. In the interest of full disclosure, I interviewed Howie for this book because he has a connection through his grandmother to the makers of Bonomo's Turkish Taffy, the flat taffy that was invented in 1912. I've never met anyone else who realizes that Bonomo is someone's last name and not a corporate acronym, so this indirect connection is impressive enough for me. Even better, Howie was a Good Humor truck driver ages ago, and in Manhattan no less. Personally, Howie is all about nostalgia: childhood memories of the grandparents, aunts, uncles, and parents who handed out wintergreen Life Savers or lime-green sourballs.

I am telling you this because Lois, Howie, and Dan collectively make up the feelings that most of us have about candy. We love it, as Dan doesparticularly the rich, luscious flavorsyet know as Lois does, that they're not exactly good for us in excess.

The more adventurous candy eaters may call candies sinfully delicious, while the guilty among us use negative words such as cavities, calories, and fat. They say such things as I shouldn't have, when they polish off a bag of nougats. For some, on the far end of the spectrum, candy and sin become deliciously literal: think chocolate underwear.

Who, though, at some level, doesn't experience that deep sense of connection, of belonging, that candy brings?

My mother, that's who. But here's the fascinating thing: my mother makes a distinction between candy and non-candy that gives her a loophole so she still gets to eat it. For example, she thinks that chocolates are candy but Life Savers are not. You know Life Savers right? The hard, sugar-based substance filled with flavorings and colorings that taste like candy? They, according to my mother, are usefullike when you have bad breath or a dry mouth. Candy, by definition, is not useful at all.

I don't agree with her conclusions, but she's right about one thing: Life Savers were for bad breath. Shortly after they were invented in 1912, Life Savers were marketed to saloon goers to cover their booze- and cigarette-smelling breath. I have no doubt that Prohibition helped buoy the popularity of Life Savers, landing them, decades later, in the most un-saloon-like place possible: the bottoms of thousands upon thousands of grandmothers purseswhere some, I'm willing to bet, still lie today.

Next page