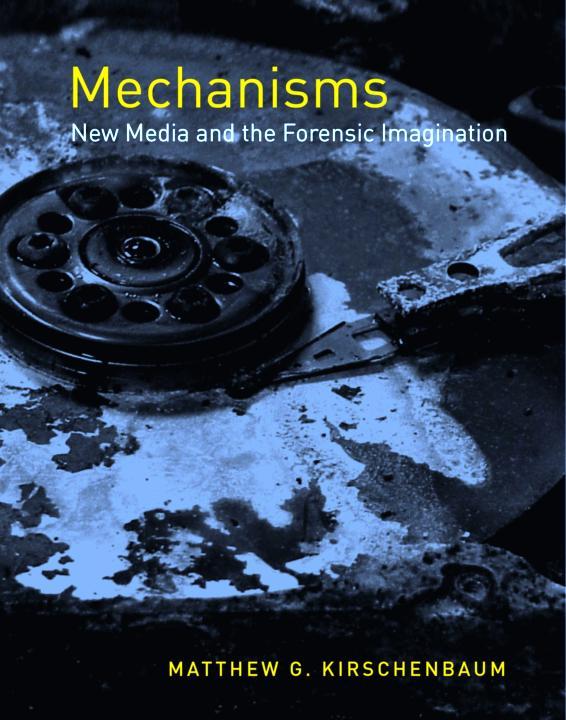

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum

For Kari M. Kraus Who bears witness

ix

-WILLIAM GIBSON, "AGRIPPA"

Explore a little further and you will find that the text, which dates from 1992, was originally published on a computer disk that came packaged with a limited edition artist's book with illustrations and etchings by Dennis Ashbaugh, also titled Agrippa. The pages of this book were supposedly treated with photosensitive chemicals that caused the images to gradually fade from view once opened and exposed to light; the electronic text of Gibson's poem, meanwhile, was encrypted so as to allow only a single reading from the disk, the lines auto-scrolling up the screen and then gone forever-a 20-minute experience.

Continue exploring the history of this strange but affecting literary artifact and every assumption about it, other than its immediate presence on the screen in front of you, is called into question. Was the text's illicit dissemination online the point of the project from the very start, or did Gibson and the others originally imagine it as an irrevocably vanishing performance piece about the ephemeral nature of memory and media? Did the data on the disk truly employ an RSA encryption algorithm as was reported, a technology classified as a munition by the National Security Agency? (If so, it would have been all but impossible to crack for anyone without the aid of a supercomputer.) Is the text of the poem on the Internet even the same as the one that was on the disk? (Early press releases about the project had more consistently described it as a short story or even a novel.) What is certain is that in Gibson's "Agrippa" we have an electronic text that is volatile and ephemeral by design, which nonetheless turns out to be one of the most persistent and available literary artifacts on the Web.

The artist's book Agrippa is more elusive-far fewer people have seen a copy in person. It comes in a literal black box, a glossy onyx-hued receptacle made of fiberglass that supports the book in a nest of webbing and corrugated the diskette, meanwhile, contains the electromagnetically encoded text of the poem sheathed within its generic black plastic envelope. (Both serve to make Agrippa an early form of what we today call "codework.") As one turns the pages, the drawings, some printed with uncured photocopy toner, rub and smear-a book that cannot help but be remade in the act of reading.

These two episodes were my starting points in thinking about this book. Taken together they dramatize the complex nature of transmission and inscription in digital settings. On the one hand we have "Agrippa," an electronic text that must contend not only with its notoriously fragile digital pedigree, but which was actually intended to disappear from sight, yet is one of the most stable and accessible electronic objects I know. On the other hand is the extreme physical trauma of the World Trade Center collapse, yet electronic data emerges intact from its ruins. Both of these occurrences and their seemingly counterintuitive outcomes suggested to me that our current theories and points of reference for reckoning with electronic textuality were inadequate when parsed against what I had come to understand as the material matrix governing writing and inscription in all forms: erasure, variability, Mechanisms is therefore a book about the textual and technical primitives of electronic writing and (by extension) other types of data recorded in electronic media.

A mechanism is both a product and a process, and making Mechanismsmaking it work-has taken me from the New York Public Library, the Folger Shakespeare Library, and the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin to the Charles Babbage Institute in Minneapolis, the Nanomagnetics Group at the Laboratory for Physical Sciences at the University of Maryland, and the Department of Defense's Cyber Crime Center, housed in an anonymous office park near Baltimore/Washington International airport. I have incurred a number of debts in this unexpectedly bilateral project, and it is my pleasure to acknowledge them here. Jonathan Auerbach, Kandice Chuh, Morris Eaves, Neil Fraistat, Lisa Gitelman, Katie King, Alan Liu, Bill Sherman, Martha Nell Smith, Catherine Stollar, and Noah Wardrip-Fruin all read large portions of the manuscript or read it in its entirety, and contributed important ideas. Nick Montfort deserves special mention and special thanks, not only for reading but for always being at the other end of an e-mail or an instant message and for first initiating me into the secrets of Mystery House over burritos in College Park. I am also indebted to my anonymous readers for the MIT Press, whose judicious suggestions and critique made the book that much better. Kevin Begos Jr., Michael Joyce, Patrick K. Kroupa ("Lord Digital"), and Alan Liu all intervened with critical data access at critical moments. Johanna Drucker, Neil Fraistat, Jerome McGann, Martha Nell Smith, and John Unsworth have each been there since the beginning or nearly so-I hope this book rewards their ongoing support of me in some small way. Professors Romel Gomez and Isaak Mayergoyz of the University of Maryland's Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering patiently answered an English professor's questions about magnetic recording and arranged for me to visit their labs. Peter Stallybrass and Rogier Chartier's magnificent Technologies of Writing seminar, which I was privileged to attend at the Folger Shakespeare Library in spring 2005, became pivotal in my thinking about the project; my thanks to them, to my fellow students, and to the Folger for that opportunity. Supervisory Special Agent Jim Christy at the Department of Defense's Cyber Crime Center, along with staff members Ryan Vella and Nancy Meyer, accommodated my visit to what may be the country's premier computer forensics lab and shared what they could of their sensitive expertise. Virginia Bartow at the New York Public Library facilitated access to the NYPL's copy of Agrippa, and Darrell Hyder at Sun Hill Press dug out his typesetter's proofs for me. Elisabeth Kaplan of the Charles Babbage Institute at the University of Minnesota helped me make the most of a morning there. Catherine Stollar of the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin and Pat Galloway of the School of Information, faced with the daunting and unprecedented task of accessioning the 50 boxes of printed matter, 400 diskettes, and the odd laptop and whatnot of the Michael Joyce Papers, generously granted me complete access to the collection before it was publicly available. They both understood what I was after from the get-go, helped me navigate the material, and made my visit to Austin a success in every way. Thanks also to the outstanding staff of the Hazel H. Ransom Reading Room at HRC. My ultrawired graduate students at the University of Maryland keep me honest and keep me up to date: Jason Rhody, Tanya Clement, and Marc Ruppel each deserve special mention. Thanks also to everyone I work with or have worked with at the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH), including Amit Kumar, Greg Lord, and Carl Stahmer. Despite the fine tunings of the many persons mentioned above, friction and flaws in Mechanisms are mine alone.