A spectacled flying fox, Pteropus conspicillatus , pollinating black bean, a highly prized hardwood, used especially for veneers.

1997 by the Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

Copy editor: Susan M. S. Brown

Production editor: Deborah L. Sanders

Designer: Janice Wheeler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilson, Don E.

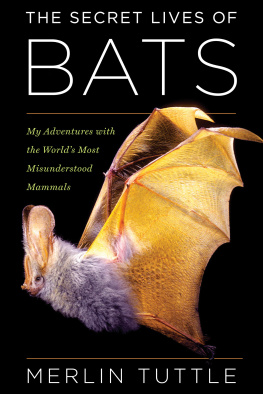

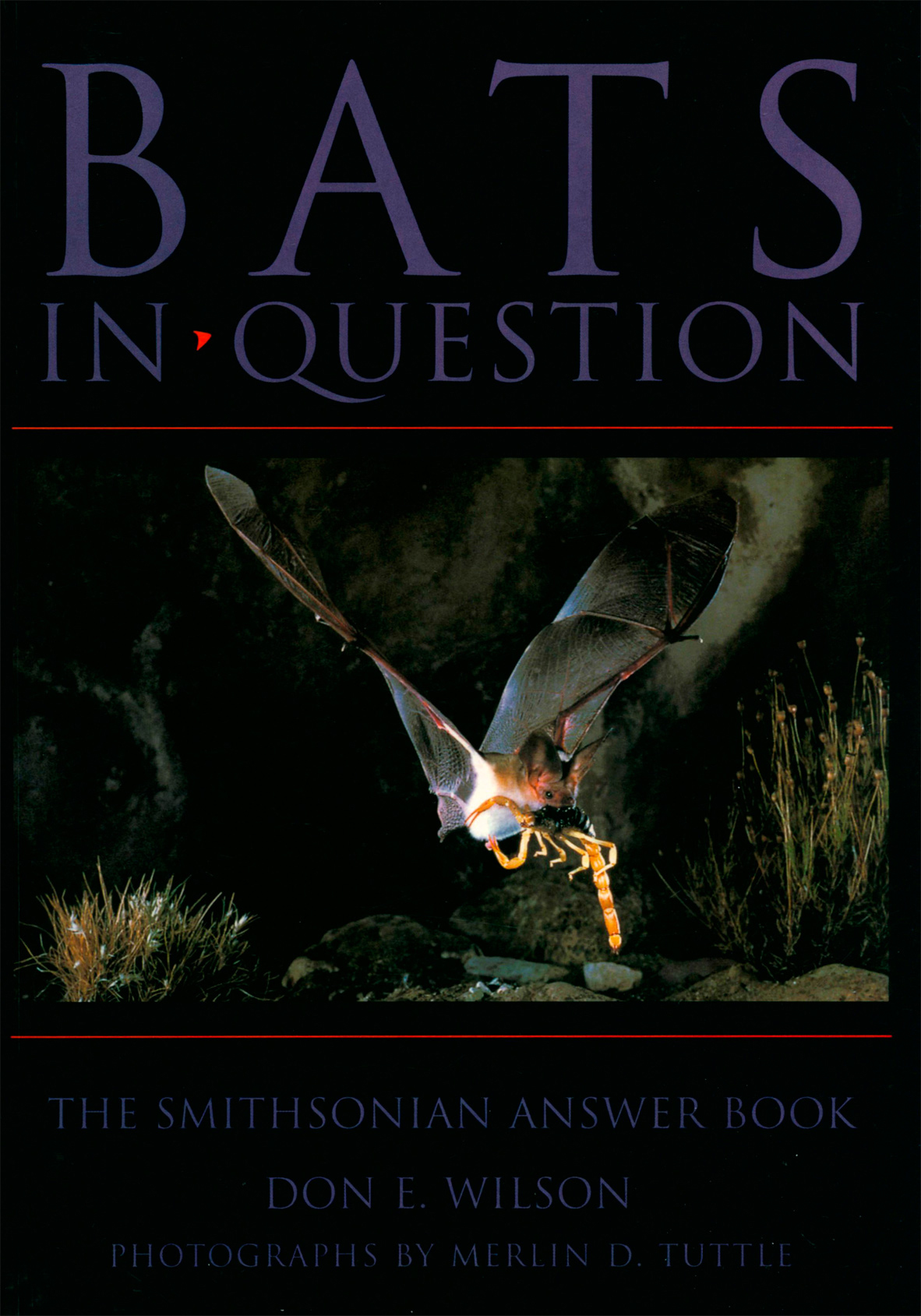

Bats in question: the Smithsonian answer book/Don E. Wilson; photographs by Merlin D. Tuttle.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58834-511-0

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-56098-738-3

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-56098-739-0 (pbk.: alk paper)

1. BatsMiscellanea. I. Title.

QL737.C5W56 1997

599.4dc21 96-30035

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available

For permission to reproduce photos appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owner of the works, Merlin D. Tuttle, of Bat Conservation International. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

This book may be purchased for education, business, or sales promotional use. For information please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P.O Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

www.SmithsonianBooks.com

v3.1

CONTENTS

.1.

BAT FACTS

.2.

BAT EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY

.3.

BATS AND HUMANS

PREFACE

Bats elicit an immediate and strong reaction from most people. Historically, that reaction has been almost uniformly negative, and bat populations have suffered as a result. In recent years, interest in bats has grown apace with appreciation of them, making bats an excellent topic for this series of books intended to inform the curious public about intriguing groups of animals.

At the same time, there has been a tremendous increase in our knowledge about these animals, especially during the last two decades. Scientists are inexorably attracted to the unknown, and until the 1960s bats represented one of the most poorly known groups of mammals. Their unique attributesflight and echolocationadded to their allure. Now, early bat biologists have begun to attract excellent graduate students. All of this, combined with the development of new techniques for studying bats, has led to an information explosion about their natural history and a concomitant concern for their conservation.

This book is arranged like others in the series. The first section focuses on the general biology of bats, answering questions dealing with basic bat biology: classification, structure, reproduction, feeding, hibernation, and migration. The second section looks at the evolution of particular types of bats, reviewing the groups enormous diversity. The third deals with bat-human interactions and explores ways people have viewed bats. In addition, the third section contains suggestions on how to pursue your interest in bats should you wish to do so. An appendix provides a complete classification of bats, including scientific and common names for all 925 species and information on the status of their populations. The two-part bibliography includes both general works on bats and specialized scientific references on individual topics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wrote this book at home in the evenings over the course of about a year. It was a labor of love, allowing me to describe a wide variety of interesting facts about bats without forcing them into the somewhat turgid prose of a scientific paper. My own love affair with bats began about 30 years ago, when I fell under the influence of Professor James S. Findley of the University of New Mexico. His own keen interest in bats, abiding respect for science, and ability to communicate both have remained a continuing inspiration for me. I would like to say a heartfelt thanks, Jim, by dedicating this book to him.

Peter Cannell, science acquisitions editor at the Smithsonian Institution Press, was supportive and encouraging at all the right moments. My colleagues Brock Fenton and Tom Kunz suggested additional questions early on in the process. My wife, Kate, read the entire manuscript, catching some remarkable errors and correctly dissuading me from some of my more flowery usages. In addition to providing the superb photographs, Merlin Tuttle read an early draft and offered me valuable suggestions and recent updates on a variety of conservation issues. F. Russell Cole, Adam Potter, and Bernadette Graham contributed considerable time and effort to generating the appendix, and I am grateful for their assistance with this and other projects.

The scientific research departments associated with the worlds natural history museums tend to be invisible to the general public, although they provide the underpinnings for all the public exhibits and education programs those museums offer. As it has for everything I have produced for the past 25 years, the Division of Mammals at the Smithsonians National Museum of Natural History gave me an intellectual home, an unparalleled collection of bats, and superb library resources. Equally important, my colleagues Alfred L. Gardner and Charles O. Handley, Jr., have shared their extensive knowledge of bats with me on a regular and sustained basis. In return for that support, royalties that accrue from this book will go to the museum for continued support of publication efforts such as this, and to Bat Conservation International to further their efforts on behalf of bats.

INTRODUCTION

Of all mammals, perhaps none are so misunderstood as bats. Because they are nocturnal, secretive, and normally seen only fleetingly as they whip by on a summer evening, bats have taken on an aura of legend. Sometimes this mystery has hampered our ability to appreciate them for what they are.

Although in most peoples minds all bats are basically alike, bats actually encompass an incredible variety of forms and lifestyles and are among the most diverse and successful groups of mammals. The 925 species of bats make up almost one quarter of the 4,625 described species of mammals. Bats occur, and are abundant, on all continents except Antarctica. Some bats are efficient predators on insects; others are excellent pollinators of flowers and important dispersers of fruit and seeds. Some eat frogs; others feed on blood. Regardless of these differences, all possess remarkable systems of navigation and flight, unique among mammals. These adaptations allow bats to operate both in the open air and in closed canopy forests, something no other group of mammals has accomplished.

We are coming increasingly to understand the pivotal role bats play in ecosystems all over the world. As more and more of us come in contact with bats, it is vital that we understand the importance of maintaining viable populations of these key species. People are expanding their recreational use of wilderness areas and broadening their awareness about environmental issues in general. Wildlife-oriented activities are becoming more and more important as greater numbers of people are forced by urbanization to live farther and farther removed from natural places and wild things. Development activities continue to take their toll on the natural habitats of all living organisms, bats included. At least 10 species of bats have gone extinct in the past 500 years, and many others have suffered devastating population declines. This list is bound to grow unless the image of bats can be changed so that people recognize their importance and value.