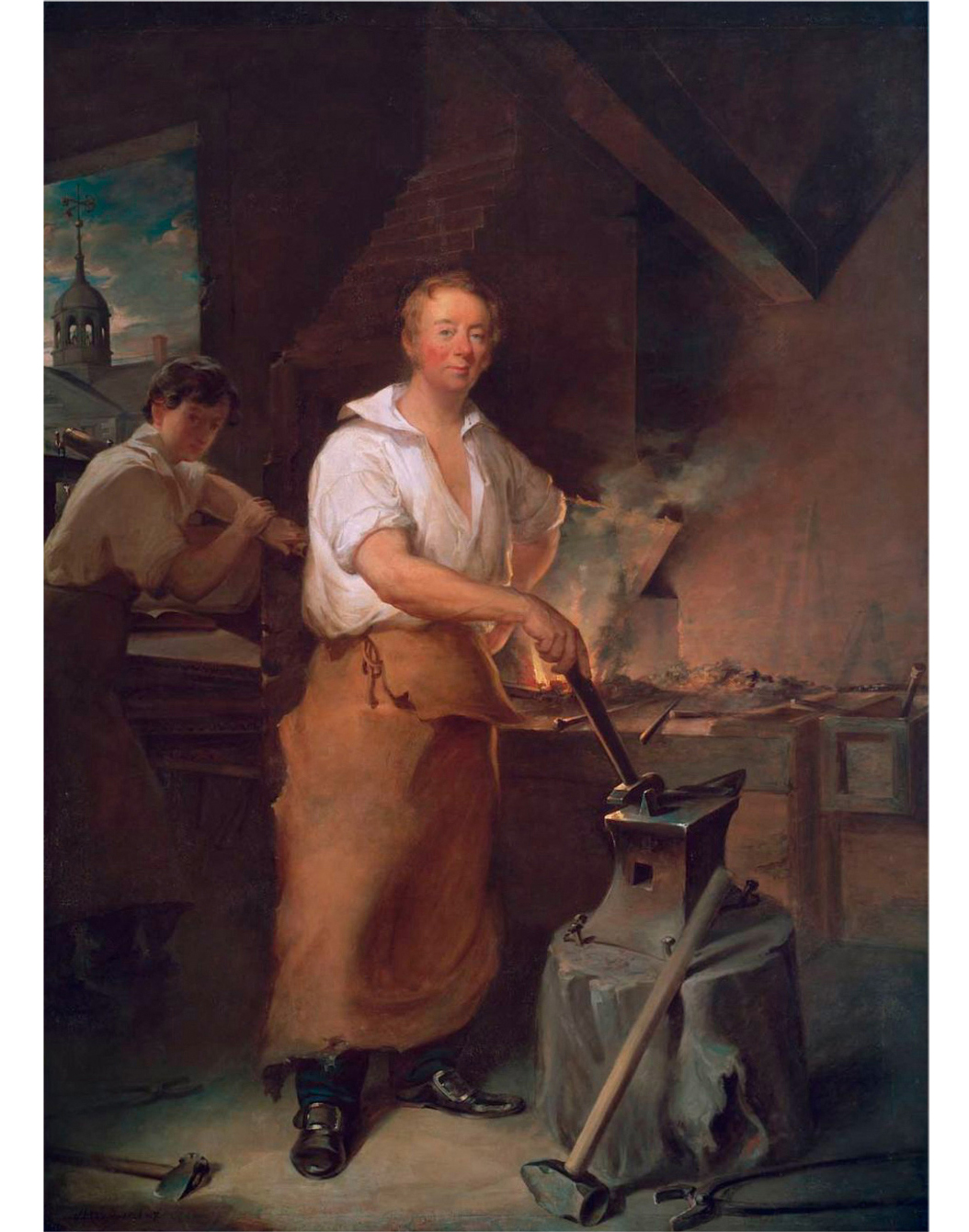

Patrick Lyon at the Forge , by John Neagle, 18261827. After refitting the doors on a bank vault, blacksmith Lyon was falsely convicted of robbing the bank. Imprisoned, he won his acquittal, plus restitution, which he used to manufacture fire engines. Lyon commissioned this portrait to indicate his pride as an American laborer.

This book may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write:

Special Markets Department

Smithsonian Books

P. O. Box 37012

MRC 513

Washington, DC 20013

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data American enterprise: a history of business in America / edited by Andy Serwer; introduction by David K. Allison; contributions by Peter Liebhold; contributions by Nancy Davis; contributions by Kathleen G. Franz.

pages cm

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58834-497-7

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-58834-496-0

1. United States-Commerce-History. 2. National characteristics, American 3. United States-Economic conditions. 4. Democracy-United States-History. 5. Capitalism-United States-History. I. Serwer, Andy. II. National Museum of American History (U.S.)

HF3021.A44 2015

338.0973dc23

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as seen in . Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually, or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

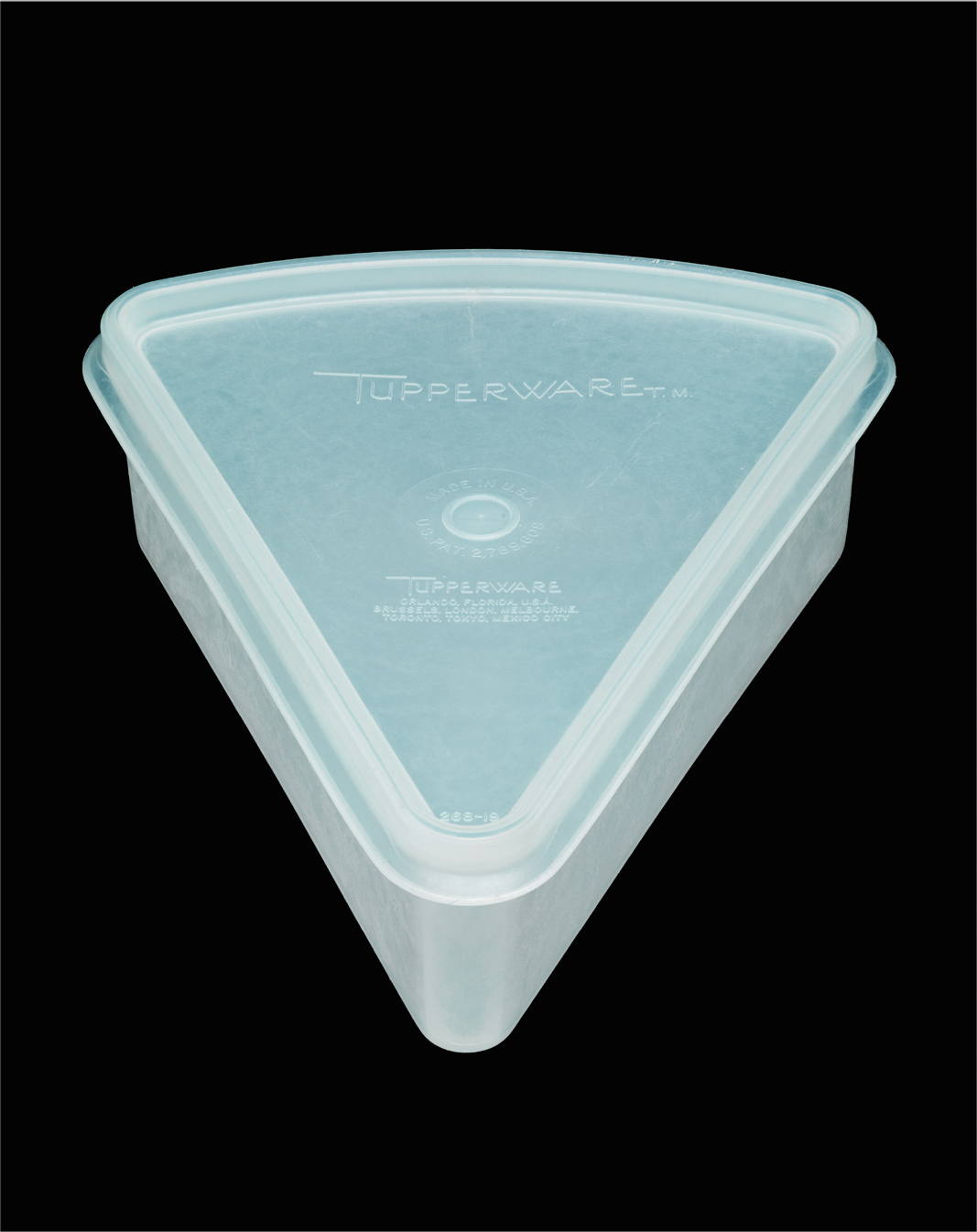

Tupperware pie wedge holder, 19471960. Inventor Earl S. Tupper molded his idea for plastic containers into a variety of specialized shapes that could hold any food item, from salad to dessert, and gave consumers many reasons to buy everything in an expanding line of re-sealable products.

Foreword

WE ARE PLEASED to be presenting the sweep of American Enterprise explored in this publication with its accompanying exhibition and multifaceted programs. Understanding American capitalism is essential to knowing how we as a Nation came to this moment, and even more importantly, what our future could be. As the museums first major initiative to present American business to the public, we take this very seriously, and are fascinated by the stories of such varied American innovators.

My favorite story in this book is about Brownie Wise, who had begun marketing Tuppers plastic containers through home sales.

Tupper contacted her after learning about her great success with this approach. American consumers, mostly women, were skeptical about plastic and rarely saw the value of the vacuum seal without a demonstration. Although Wise didnt invent the home selling strategy, she adapted it and tapped into a growing desire among married, middle-class women to contribute to the family income. Wise made selling fun and lucrative, and thus turned Tupperware into a household standard.

Today the National Museum of American History preserves elements of this quintessential American story in both dozens of examples of early Tupperware and archival papers from both Tupper and Wise. It is but one example of how the institution is preserving, interpreting, and sharing the remarkable history of American Enterprise .

Traditionally our museum presented highlights of its broad collections, which number over three million artifacts and records, and document everything from medicine to music. But in recent years we have learned that our visitors are more interested in seeking answers to provocative questions: what does it mean to be an American? What are the ideas, ideals, and realities that have defined the American experience?

American Enterprise aspires to answer these questions about the history of American business and innovation. It tells the story of what happened when capitalism and democracy met in North America and shaped a nation of people eager for economic opportunity and willing to embrace innovation and change. But this new exhibition will not stand alone. The museum is also exploring related areas, including how democracy was implemented in the United States; how immigration and migration changed national beliefs and values; and how new cultural expressions have shaped American identity at the individual, community, and national level.

Interspersed throughout this book are essays of leading thinkers in todays business community, who present contrasting views on important contemporary issues. Debating enterprise has always been part of American history, from the time when some colonists argued that remaining British was best for business, while others passionately sought independence. I hope this mix of historical narrative and contemporary deliberation will challenge you to define your own views about the best direction for American business and innovation in the future.

JOHN L. GRAY

Director , National Museum of American History

Statue of George Washington, 1792. Jean-Antoine Houdons statue of Washington, begun in 1785, stands in the Virginia State Capitol. Although Washington is depicted in military dress, he is accompanied by both civilian (plow and cane) and military (fasces, sword, and uniform) objects.

Introduction

AUGUST 15, 1786. George trade, there will assuredly come a day, when this country will have some weight in the scale of empires (Fitzpatrick 1938, 518521).

In Washingtons eyes, that weight should come through expanded commerce, not military power. He continues, As a citizen of the great republic of humanity at large I cannot avoid reflecting with pleasure on the probable influence, that commerce may hereafter have on human manners and society in general. I indulge a fond, perhaps an enthusiastic idea, that, as the world is evidently much less barbarous than it has been, its melioration must still be progressive; that nations are becoming more humanized in their policy, that the subjects of ambition and causes for hostility are daily diminishing; and, in fine, that the period is not very remote, when the benefits of a liberal and free commerce will, pretty generally, succeed to the devastations and horrors of war.

Like most of the founders of the United States, Washington was at heart a businessmannot an aristocrat or even a warrior. He had fought for independence primarily for economic, not political reasons. The fundamental question had been who would benefit from the economic growth of Americaabsentee colonial landlords or the people of America themselves?